There is a story that actor Terence Stamp recounts in his memoir The Ocean Fell into the Drop that has become deeply embedded in his legend. It goes like this: when director Federico Fellini was looking to fill the lead role in his film Toby Dammit (part of the anthology film Histoires extraordinaires ), he approached the top casting director in London and asked him to send “the most decadent actor in England” to audition for the part. The casting director – without much hesitation – immediately sent him Terence Stamp.

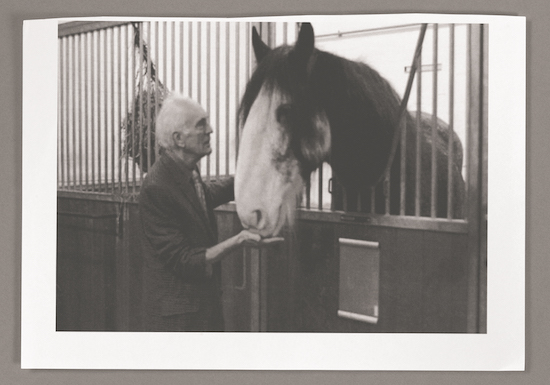

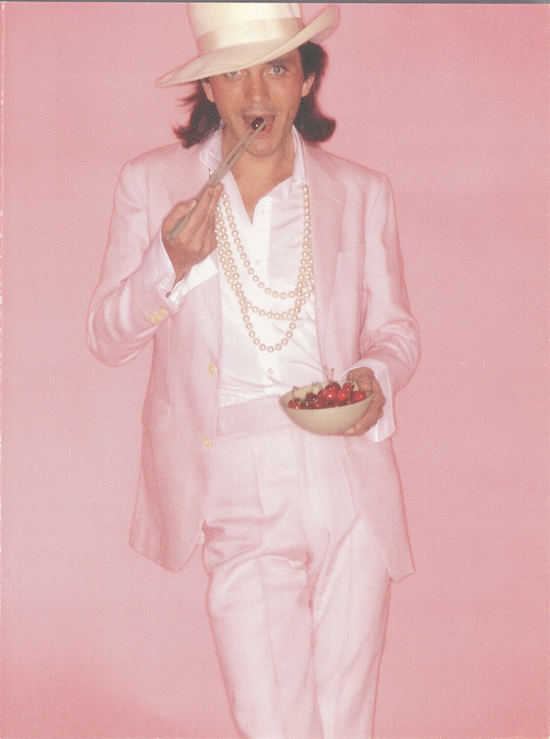

Terence Stamp is living film history. He has worked with some of the best and most interesting directors to grace the medium, from old Hollywood legends such as William Wyler, to social realists like Ken Loach, to the titans of the European avant-garde in Pier Paolo Pasolini and Federico Fellini. He nearly singlehandedly popularized a new type of on-screen cool, affecting the bearing of an otherworldly East End aristocrat, radiating a detached debauchery from behind his piercing blue eyes. Recognized as something genuinely new and revolutionary on screen, Stamp was given the title of world’s best-looking man (1963–1969), and he put it to use, dating Jean Shrimpton, Julie Christie, and Brigitte Bardot.

In keeping with his off-screen persona of towering decadence, he portrayed a mysterious messianic sex-god in Pasolini’s Teorema, and a dissipated and morally corrupt alcoholic actor in Fellini’s Toby Dammit. Elegant and aloof, Stamp typified a strain of emerging British masculinity and was at the vanguard of a new wave of Sixties celluloid sex appeal.

The Sixties truly belonged to Stamp. He was friends with John Lennon and the artist Francis Bacon, and was even offered the role of James Bond after Sean Connery decided to step down from the part.

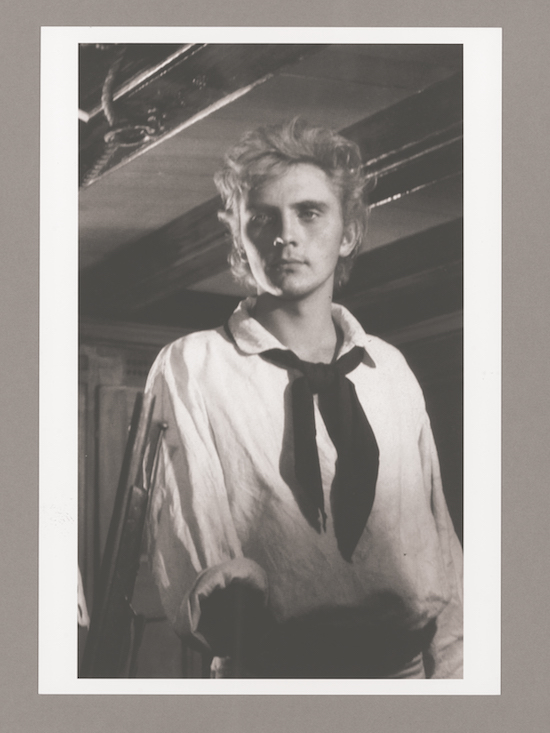

Haven broken into film at age 24 in Peter Ustinov’s Billy Budd (a role for which he immediately earned a Golden Globe win and an Oscar nomination), his career went from strength to strength – until suddenly it all stopped.

Stamp has said that “when the sixties ended, I ended with it," and with his opportunity to play leading roles drying up (and in the wake of a bad breakup with Jean Shrimpton), he left England for India. Finding his way into the ashram of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh – the very same guru recently profiled in the Netflix series Wild, Wild, Country – Stamp would take on a new name, study tantric sex, and seek spiritual enlightenment for the next nine years. That is, until he received a telegram from his agent that read: “Could you return to London for Superman 1 and 2 to be directed by Richard Donner? Your part would be General Zod. You have scenes with Marlon Brando.”

He agreed to the role, and the second act of his career was effectively launched.

With some exceptions, Stamp would largely leave behind the leading roles he was known for in the Sixties and instead become a character actor. Since then he has gone on to appear in the films of Michael Cimino, Tim Burton, Steven Soderbergh, Oliver Stone, Stephen Frears, and George Lucas. His career has seen him sharing the screen with everyone from Laurence Olivier to Marlon Brando, and acting in everything from independent arthouse films to budget-busting blockbusters.

In my conversation with him we discussed the arc of his career, from his very first role to his future cinematic ambitions.

In your memoir The Ocean Fell into the Drop you talk about one of your earliest memories at the cinema where you saw Beau Geste featuring Gary Cooper. I wanted to ask you about that moment and what it meant for your future in acting.

All I can say is it must have been a really profound moment for me. It was the first film I ever saw, and unbeknownst to me he was one of all the all time great cinema actors, so I was affected by one of the best. Because our family was of a thoroughly working class background it didn’t really occur to me to do anything like performing, it just occurred to me that I wanted to see as many films as I could after that. It wasn’t until I left school and was in a job that I realized that I must do this – I must try this, and that’s how it came about really.

Your first feature film was Billy Budd, directed by Peter Ustinov. How did it come about and what was it like for you as a first shoot?

It was extraordinary. I remember my agent telling me, I want you to go to ABC studios to meet the casting director Bob Lennard, it’s about this thing Billy Budd. I said, but that’s Melville; that character is like an angel, I can’t play that – and he said “don’t worry about that, he’s asked to see you.” Apparently Ustinov had seen every other young actor in London and he said to the casting director “is there anybody else?” I was completely unknown, I was a theater actor, and when I walked in there I was so overawed by the presence of Ustinov that I couldn’t bring myself to answer any of his questions. Unknown to me, that was what he was looking for.

He was a genius, there was something really evolved about Ustinov, he was kind of saintly really. So I give him 90% of the credit for that role because I just didn’t have any idea how to do it and he – the way he directed me and the way he told me things – caught a side of me that I was not very aware of actually.

Around this time you were sharing a flat with Michael Caine. How did the two of you end up meeting?

When I was in the theater there was a play that had been a big smash at the time, and it was a play that starred Peter O’Toole and had made him a famous theater actor called The Long and the Short and the Tall. What had happened was Michael Caine had understudied O’Toole for a year, and had never gotten on [stage]. Even though Peter O’Toole was roaring drunk before every show, when his feet hit the stage he was sober. So when the play went on a tour of England, Caine took that part.

What happened was they ran out of dates, so it was canceled, and then they suddenly got a lot more dates, but the cast was gone and they had to put a cast together very quickly and they didn’t have the Juve. Somebody asked who it was that played [that role] in Richmond; so I was asked to do the tour.

So I did this tour of England with Michael Caine and when the tour finished he asked me if he could come and stay in the apartment that I had with two other guys, and I said yes. After he had been there for a week or so he said to me “these guys are not your speed, why don’t we get a place together,” which we did. But in fact, as soon as he made it, he didn’t want me around!

I’d like to talk about your work with director William Wyler on The Collector.

I had been approached by the producers because when Billy Budd came out I got this five minutes of fame, I was all over the newspapers and stuff. So they approached me and sent me the script, and they sent me the book [by John Fowles]. I said “I’m totally wrong for this, I can’t do this.” They came back to me several times and I said “guys I’m wrong for it, you know?” Then they came back to me and they said “we’ve got William Wyler, are you going to turn down William Wyler? “ I said, “well, who is the girl [I’ll be playing opposite]?” And they said “Wyler is having somebody test two or three girls.” I said, “why don’t I do the test with the girls.” I imagined as soon as Wyler saw the tests he would see I was wrong.

Wyler flew to London to see the tests and asked to see me, and I remember this very diminutive guy coming out of a room in the old Columbia building in Wardour street, and he walked down this long passage and came close to me. He didn’t speak, and I was a bit unnerved, so I said “what?!” and he said “yes,” and I said “I’m not right for this,” and he said “yes.” And I said, “well in the book…!” and he got close to me and he said ‘we’re not going to make the book.” And that was how I began working with William Wyler.

What was it like working with Wyler?

It was one of the great experiences of my life. He was just wonderful in a way I’ve never come across before. It wasn’t an accident that he was one of the leading film directors in the world. He was just extraordinary, the way he coaxed that performance out of me.

What was London like in the Sixties? You mention in your book that you would often run into John Lennon and that you were friends with the artist Francis Bacon. It seemed like an incredible time.

Yes, but I didn’t realize how incredible it was. I thought this is what being famous is like! It wasn’t until ‘67 or ‘68 that we all began to realize there had been this amazing shift happening in London, in the world, really. I guess it started or germinated in London.

It was while working on John Schlesinger’s film Far from the Madding Crowd that you met Nicolas Roeg, who was the cinematographer. You write lovingly of your encounter with him in your book.

Schlesinger didn’t really want me. He had somebody totally different in mind [for the part] and the producer dragged me in over his head. That’s not always a good start between a director and an actor, so the fact was he didn’t have a lot of time for me, and Nic Roeg did.

Schlesinger had done a kind of minimal shooting of the sword sequence in the film and Nic said to me “after we finish shooting we’ll get some extra footage in,” and I said “really?” and he said “yeah.” It happened like three or four times after shooting, he’d say “get your sword.”

You would go on to star in Poor Cow, Ken Loach’s first feature film. Apparently there was no dialogue scripted. That must have been such a different way of working, especially from Wyler, who was known as this perfectionist.

In truth, once I realized what was going on, it was a wonderful release, because prior to getting into drama school I had been to a very amateurish Method Acting school…but that had been only improvisation, so it wasn’t new to me. What was unusual with Loach was that he would tell Carol White something and then he would come up and tell me something completely different, but he would whisper to us. He was creating this kind of real improvisation, so you really didn’t know what was going to happen. It was the strangest thing, but it was wonderfully freeing because after that I had a kind of another dimension of confidence when I was in front of the camera.

After working with Fellini on Toby Dammit you worked with Pier Paolo Pasolini on the film Teorema. Was that experience much different?

Yes, the truth of that was that as a boy, or a teenager, I had seen Silvano Mangano in a film called Bitter Rice, and I had a crazy infatuation with her. She was one of the most staggeringly beautiful women I had ever seen.

When I was in Rome – I think I was doing a bit of looping for Fellini – and I was walking down Villa Condotti and I saw her, and although she was much older, she was unmistakable. She was with a guy called Piero Tosi, who was the costumist for Fellini, but he was also one of the great fashion people of Rome. He said “Terence Terence! Silvano, this is my friend Terence!” And she was looking at me and she said to Tosi in Italian that I would be wonderful in Pier Paolo’s film. Then she turned to me and she said in English “you are familiar with the work of Pasolini?” and I said no. She said “he is a wonderful director who is making a new film, and you would be wonderful in it.” And I said “are you in it?” and she said “si si, certo.” She told Pasolini, and as a result he flew to London to see me.

He didn’t speak any English at all, but the guy who produced it was a nephew of Visconti, and he translated. I went to meet him at Claridge’s, which I thought was strange for such a kind of ‘left-wing everyone should be equal’ kind of guy. He said to me through the translator that [Teorema] is the story of a young man who has a divine nature. He arrives in the home of this bourgeoisie family and seduces the wife, the husband, the maid, the son – and I said, “I can do that!”

You weren’t arguing with that role.

I wasn’t arguing with that role! And that was it, it was a very brief meeting and I went to Milan and he never spoke to me, he never directed me. He just let me get on with it. He was a guy who, like Ken Loach, had his own second camera so he was shooting a lot of stuff when I was just on set. Ken Loach only really shot between action and cut but Pasolini just shot; he seemed to have this camera all the time.

In keeping with this sort of decadent image you were cultivating, Harry Saltzman around this time approached you about taking the role of James Bond after Connery. Apparently you had some ideas about the role that scared him.

That was my assumption. I wasn’t nervous about taking over, it was just that Connery had been so successful and I just wanted to make sure Saltzman would let me do it my own way, and obviously the last thing he wanted was some young temperamental actor! I just never heard from him again, so I just don’t really know.

I’d like to take credit for it, but I just don’t know whether it was that or whether he just didn’t think I was right when he met me. He might’ve thought I was too young, I just don’t know. But I did have ideas about it and on reflection, because I didn’t get to know him but I heard about him, apparently he was a real egomaniac who would have loved to direct the films himself, so it’s possible that the last thing he wanted was an actor with ideas.

After 1969 you had a lull in your career.

I knew that lots of big actors had lulls in their career, but generally it was either at the beginning or the end, like Jack Nicholson [who] didn’t get his break until he was in his thirties. So for me, because I was so successful, I didn’t have any kind of comprehension as to why everything had dried up. Every day waking up was a nightmare, from being a real success to nothing.

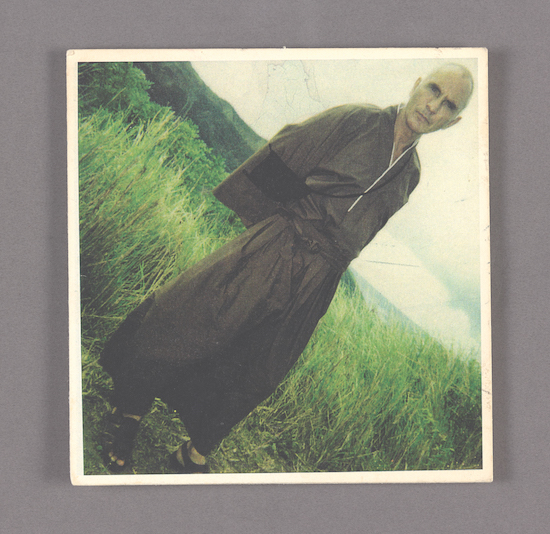

At the time I had been introduced to [Jiddu] Krishnamurti, but frankly [his teachings were] above my head, I couldn’t make sense of it, but at the same time I realized that there was something exquisite about the man. I thought, it’s me being dumb, he’s not trying to mislead me, so I thought maybe if I go to India I can start a bit lower down the ladder. I didn’t have much idea, and it turned out to be a very long stay.

You stayed in India until you were contacted about starring in Superman I and II as General Zod. How did that come about, especially since you weren’t looking for work at the time.

I had been ensconced in an ashram. I didn’t realize how novel the ashram was at the time, or how unusual the guy was, but it was the ashram that had been put together by Bhagwan Rajneesh, and I didn’t realize how he had made himself into this famous guru. I just knew that everybody, all the young people I met were wearing orange. And I said what’s this orange [about], oh well it’s Rajneesh I was told, so I thought to check him out.

The first weekend I was there I was invited to live in the ashram and frankly, the thing that struck me about him was that he was one of the greatest performers I had ever come across. He was like a mixture of sort of a Charles Laughton and Orson Welles; he was probably the greatest public speaker I have ever come across. He was mesmerizing, he could hold an audience, talk for an hour, no notes, nothing. So he became the focus of my attention. I became ensconced in the ashram, I had a new name, I was wearing orange, I was studying tantric sex. It wasn’t uninteresting!

So when a telegram arrived and I opened it, it was from my long suffering agent James Frasier: could I come back to London to meet Richard Donner about Superman I and II, with Marlon Brando! And what was interesting was I went to the guru and I said to him “I’ve been offered this big job in England,” and I didn’t expect his response, and he said “go with my blessing Viten,’ –which is the name he had given me – and I was on a plane the following evening, in orange.

What was it like sharing screen time with Marlon Brando?

It was heaven, because he was such a wonderful guy. The first time I set eyes on him I went on the set, still in orange – I must’ve cut a really strange figure – and he was there with these two rather beautiful sisters, as it turned out. They were giggling, whispering to him and giggling. He came over to me and the first thing he said was “Hi, I’m Marlon,” as if I didn’t know, and I said “lovely to meet you.” He said “see those two chicks over there?” and I said “yeah,” and he said “they want your dick.” Those were the first words I heard from Brando! He was at that point in his life where I guess he wasn’t taking it seriously.

They could only afford him for a week or ten days or something. All his stuff was shot, his singles were shot. In other words they didn’t have time to have him as an eye line for the other actors, but on that very first take I was his eye line. For me, I’m working with Marlon Brando so I’m deadly serious, but I have to give him credit because as soon as he realised on ‘action’ that I was taking it seriously, he was right there with me. So I did get the full Brando experience as an actor.

And then they cut him out of the film!

They cut him out, and the reason was that when the first film made so much money he claimed his percentage, which they had to pay him contractually, but they weren’t going to do it for part II. However, a few years back I think after the producers died or sold the rights they reinstated all of Marlon Brando’s stuff, so there is a print of Superman II with all the Brando stuff. It’s there, you can get a video of it, so at least I did get to work with Marlon, albeit 15 years after the original release.

What was it like working with Steven Soderbergh on The Limey?

It was just wonderful; it was just an absolutely wonderful experience. The sadness was that he came to me afterwards and said that they were thinking of doing a sequel and asked was I up for it, and I said, of course. Then he told me the scriptwriter didn’t want to do it and I said to Steven “why don’t I have a crack at it?” He said “I didn’t know you wrote,” and I said “I’d like to have a crack at it” and he said “yeah great.”

It was one of those moments where I really felt inspired, it just fell out of my hand, and I sent it to him and he, I think I was in California and we had a meeting, and he told me he thought it was good but he decided he was giving up movies – which was incomprehensible – and he said “well you should direct it.” I thought to myself, yeah, this is what he does, he charms people, he’s got this endless charm – and I never heard from him again. It was one of the big disappointments of my life because of what happened, but also because it showed me a side of him, and he gave it up because he wanted to paint.

He wanted to give up the cinema for painting?

Yes, that’s what he told me.

You’ve worked with an incredible array of directors and artists over the years from Michael Cimino to Oliver Stone to Tim Burton, just to name a couple that we haven’t touched on. Is there anyone, living or dead, that you would have liked to work with?

I was flown to Spain to meet Orson [Welles] and I had a wonderful evening with him, and I was sad that [film] didn’t get made, but I don’t really think in those terms anymore. I’m not trying to wind down, it’s just that it’s more irksome for me to fly around the world now. There was a film I made, I don’t know what it was called in America, but it was called Song for Marion [released as Unfinished Song in the US], and it was the best thing I’ve ever done in the sense that those moments in Billy Budd and in The Collector, where I was inspired – that happened in every take of that movie.

Harvey [Weinstein] bought it, and he said “were gonna do this, it’s the greatest” and then he did fuck all, which is not surprising now that the real Harvey Weinstein is revealed, but the fact was that nothing really happened after that. I haven’t played a lead since then, so I think that there is a kind of natural end in sight.

So I don’t have any ambitions anymore. I think I’ve realized all my ambitions in terms of wanting to be a movie actor like [Gary] Cooper. I can’t think of anything I haven’t done, other than work with Orson.

The Ocean Fell into the Drop: A Memoir by Terence Stamp is published by Repeater Books