1971 was a watershed year for the British Board of Film Censors: Ken Russell’s The Devils hit the examiners squarely between the eyes, quickly followed by Sam Peckinpah’s Cornish Western Straw Dogs and Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange – the former rural, passionate and earthy, the latter urban, icy and clinical. For many critics, and many cinemagoers at the time, it seemed as if the floodgates had opened for a tidal wave of explicit sex and violence, and there were loud calls for the newly-appointed BBFC Secretary Stephen Murphy to, as we would say now, ‘consider his position’: Fergus Cashin wrote a column for The Sun demanding, ‘Why Can’t I Take My Family to the Pictures?’, and accused Murphy of launching an attack on public standards of decency.

Forty years on we have a cultural landscape that would make both Fergus Cashin and Stephen Murphy throw up their hands in horror and disbelief. Back then, on an August day in 1971, Murphy and Straw Dogs producer Dan Melnick could be found poring over a movieola as the American tried to convince Murphy that what he was seeing in the film’s second rape was not sodomy but rear entry (he made his case, and saved the film from far more savage cuts as a consequence). Earlier this year, the BBFC examiners were presented with The Human Centipede 2: Full Sequence, in which a man, having sewn together a chain of people mouth to anus, anally rapes the last one in line with barbed wire wrapped around his penis.

Human Centipede 2 (first banned and then passed at ‘18’ after significant cuts) is an example of a breed of extreme film-making that is today causing the British Board of Film Classification (as it was renamed in 1984) no end of trouble: the remake of I Spit On Your Grave and A Serbian Film were both cut last year, the latter having more than four minutes of footage removed. This may not come as a great surprise when we learn that the film includes the sight of a man’s throat being torn out in close up, and of another being killed by having a prosthetic erect penis forced into his empty eye socket. However, neither of these scenes was cut. The BBFC’s concerns were with the sexual violence of the film, and some very particular moments which the examiners felt contravened their policy on such scenes. But what is that policy? How has it been formulated, and how is it put into practice in the offices of the BBFC at Soho Square? And what are the deeper implications for contemporary filmmakers and audiences?

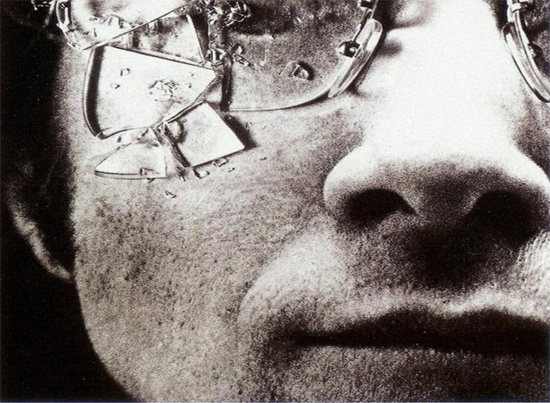

It’s a long way from there to here, but one could argue that it is Straw Dogs that provides the compass and the roadmap. In Peckinpah’s film, an American peacenik academic (David Sumner, played by Dustin Hoffman) and his young British wife (Amy, Susan George) return to her home village. The residents slowly turn on them as sexual jealousy and latent violence explode in a rape scene and, at the film’s climax, a farmhouse siege that leaves six dead. Oddly enough, after some initial consultation on a rough cut, Straw Dogs was granted an ‘X’ (the equivalent of an ’18’) without further edits. And the truth is that, while many critics found the violence of the siege scene repugnant, the film’s sexual violence did not create much of a stir at the time, except amongst a few more enlightened critics (mostly women). The description of the rape scene offered in Newsweek gives some idea of how Neanderthal the gender politics of the time could be: ‘A masterful piece of erotic cinema, a flawless acting out of the female fantasy of absolute violation’ is how Paul Zimmerman referred to it. Today, that kind of comment would hopefully provoke the kind of howls of incredulity not heard since Danny Dyer suggested in Zoo magazine that a jilted reader should ‘cut his ex’s face so that no-one will want her’. But if the rape scene in Straw Dogs was not a major problem in 1971, how did the film come to be banned in the UK for eighteen years?

The answer lies in that ‘erotic cinema’ phrase of Zimmerman’s, and in a curious quirk in the history of UK censorship: Straw Dogs was effectively caught under the wheels of legislation aimed at exploitation movies, when the “video nasties” moral panic of the early 1980s led to all home videos being removed from the shelves and submitted to the BBFC for certification (or rejection). For Secretary of the Board James Ferman, Straw Dogs became something of a totem, and he repeatedly refused it a certificate; indeed, he would make a point of screening it for newly appointed examiners as a benchmark of what was unacceptable. In Peckinpah’s film, what starts as a sexual assault on Amy by her ex-boyfriend Charlie turns into something like consensual sex: it is only the second rape that is simply and unequivocally brutal. Ferman claimed the film endorsed the familiar male rape myth that a woman may say no when she really means yes. Meanwhile, despite a riveting performance from Susan George, who imbues the character of Amy with a far more complex set of emotions than was initially intended by Peckinpah, there is no doubt that the scene is shot in such a way as to emphasise the eroticism.

The reasons given to refuse a certificate to Straw Dogs on home video in the 1980s effectively shaped the Board’s policy on sexual violence that has remained in place ever since. Any representation of rape that the Board feels ‘eroticises’ or ‘endorses’ the act is likely to be cut. It was not until Ferman retired that the Board began to open up a dialogue with the public via consultations and surveys. Armed with reports from psychologists who denied the film could have a harmful effect on viewers, the Board executed a remarkable U-turn and finally allowed an uncut release of Peckinpah’s film in 2002.

Almost ten years later, Rod Lurie’s remake of Straw Dogs has arrived. The controversy is very different this time around, and far more muted, but still haunted by the spectre of sexual violence: Lurie has provoked the ire of many Peckinpah fans by taking his predecessor to task for depicting Amy, as Lurie put it, ‘cuddling with her rapist’. He has no intention of either eroticising or endorsing rape in his film. On this, Lurie and James Ferman, were he still alive, might have found they had considerable common ground.

Today, the issue of sexual violence remains the most tightly knotted problem at the heart of debates about censorship in this country. However, reflecting on the evolution of Board policy over forty years of censorship reveals a fascinating irony: the sexual assaults it finds acceptable today are those that are the least erotic (as in Gaspar Noé’s Irreversible (2002), which was left intact by the examiners). In other words, the depiction of anal (or rear entry) rape in Straw Dogs that troubled Stephen Murphy so deeply in 1971 has become the least problematic for a contemporary examiner at the BBFC.

But the role of the BBFC in regulating sexual violence does not end here: the extended classification information on A Serbian Film claims that, after the cuts the Board have demanded, the film’s ‘scenes of very strong sexual violence remain potentially shocking, distressing or offensive to some adult viewers, but are also likely to be found repugnant and to be aversive’. The implication is unmistakeable: as a consequence of the Board’s cuts, it is simply a better film.

Forty years after Straw Dogs producer Dan Melnick wrote to Stephen Murphy, with gentle irony, that the Secretary discharged his duties in such a gentlemanly way that ‘it is almost a pleasure to be “censored”’, the Board’s practices remain unchanged and just about unchallengeable, despite greater transparency and apparent accountability. The guidelines are clear; and when filmmakers fail to keep their movies within them, the Board’s examiners will effectively take over the directorial role themselves, and shape the films to make sure they do.

Rod Lurie’s Straw Dogs opened nationwide on November 4th.

On November 9th there will be a special screening of Peckinpah’s film at the Barbican, London. The showing will be followed by a conversation about the film and an audience Q&A with the film’s co-star Susan George, Peckinpah’s long-time assistant Katy Haber, censorship expert Julian Petley, and the author of this piece Dr Stevie Simkin

Dr Stevie Simkin is Reader in Drama and Film in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Winchester, UK. His book about Straw Dogs for the new Palgrave Macmillan series Controversies has been described by Peckinpah biographer Garner Simmons as "Exceptionally well-written… needs to be read by anyone interested in understanding Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs as a serious work of cinematic art’.