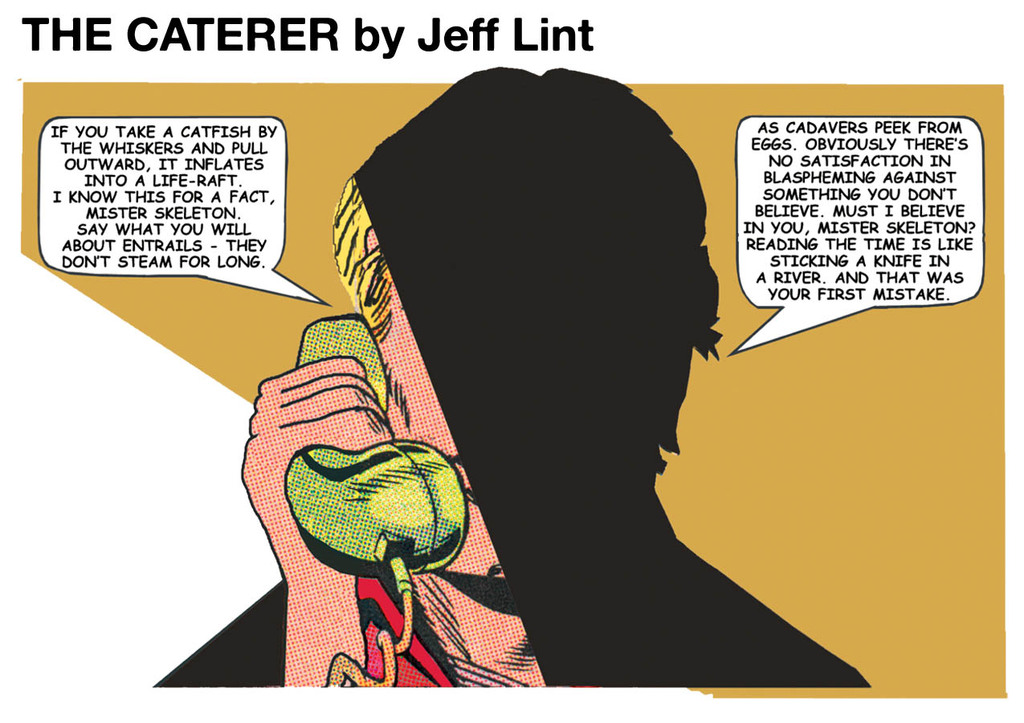

Who could forget Jeff Lint? Well, it seems almost everyone. But thanks to Steve Aylett’s superb biography and now film, those in the know are once again coming to love, despise or be baffled by the author of I Blame Ferns, Nose Furnace, Jelly Result and countless other titles. Lint was first published, in 1943, when he submitted his short story ‘And Your Point Is?’ under the pen-name Isaac Asimov. He would go on to write prolifically, despite abounding rumours of his death, expanding out into other forms such as the epileptic-fit inducing cartoon Catty & The Major, the action hero comic The Caterer (whose hero is “never seen to cook or prepare food in any way”), and adopting Captain Beefheart’s “enforced psychodrama” rehearsal techniques for the concept album The Energy Draining Church Bazaar with The Unofficial Smile Group. As Alan Moore states in the film, “He was an extraordinary man, who ranged over an extraordinary number of things and… I hated most of them.” My favourite Lint anecdote is his theory that the bullet that killed JFK was in fact the same bullet John Wilkes Booth fired at Lincoln in 1865, which then ricocheted around the world for the next 98 years taking part in almost every major political assassination.

In his biography, Steve Aylett has produced a hilarious account of Jeff Lint’s criminally ignored, but always fascinating, life. In both Aylett and Lint’s writing there are enough ideas in each sentence to fill a whole novel. Aylett’s richly evocative satire has made him one of the leaders of the burgeoning Bizarro literary movement, with Michael Moorcock calling him “the most original voice on the literary scene”. Beginning with 1994’s The Crime Studio, Steve Aylett has written fourteen novels, two short story collections, and one set of literary essays on Jeff Lint’s works. And now Lint The Movie offers more commentary on the myth from the likes of the aforementioned Moore, Stewart Lee, Robin Ince, Josie Long, Mikey Georgeson, and many others, including Aylett himself. A long time fan of his books and having seen the film twice now, in Brighton and Northampton, I sent Mr Aylett some questions via email.

I think of your writing as an innovative combination of the ultraviolent, the hilarious and the poignant. That line from The Inflatable Volunteer – “Unachieved, my destiny drums its bony fingers as I snore” – often comes into my head. How do you think of your writing?

Steve Aylett: If I have to put it in a category I would choose satire, Voltairian satire for starters. But it’s a very specific-rich and often vividly visual version of that, where ideas can be seen as shapes and movements. The result is psychedelic and sensible. Zooming through glowing meaning-structures as they recombine into different configurations. I have this synaesthesia thing and part of that is that I see ideas and arguments as shapes and textures, like revolving sculpture. So if there’s a hole in an argument there’s visually a hole in it. Or a tangled twist and stuff that doesn’t meet up, if someone’s twisting an argument. A lot of people see ideas this way, but many convince themselves that they think in words or whatever – in the same way that many or even most people probably see music, but they tell themselves that they don’t because it’s considered an odd notion. I can’t imagine what music would be without seeing it. In regard to the writing, what I stated about Lint’s writing is true of mine, in that it’s pointillist – every sentence comes directly at you and is the head of a plumb-line of information and ‘stuff’ that you can either pull up or not. This is one way of compressing information without resorting to unreal academic terms. Satirically it’s fun to find the sweet-spot in a subject, the touching of which brings out all the reactions. Just putting the word ‘state’ before the word ‘police’ goes a long way. ‘State police’ – it’s true and annoying, so make it a habit.

You’ve been doing one-off showings of Lint The Movie, in London, Brighton and Northampton, with plans for screenings in the U.S. in November. How have they been going? How is the film being received?

SA: People who’ve seen it seem to like it. It’s good considering it was made for nothing. But the technical quality is such that I think that does need to be borne in mind. I do a sort of stand-up intro beforehand to prepare people…

The film took what, three years to make?

SA: It was more than four years. I just did it, not knowing what I was doing at any stage. I bought a crappy camera and started filming people. I did all the animations myself, but didn’t have an animation app so I drew everything, scanned it in, photoshopped it and then made these really long animation gifs, which I saved to Quicktime. The filming of the interviews and stuff was great fun, all of it. I really enjoyed it, and I rarely enjoy anything. But as soon as it got past the filming and on to the editing, everything stopped. I didn’t have an editing app or any money to buy one, or a computer workable enough to hold it or, again, any money, or any knowledge of how to edit. So I farmed it out to people who basically volunteered. About three years later, it’s still not entirely finished editing. It’s been so frustrating I’ve more or less given up on it getting beyond the current version. It’s serviceable, in fact it blows some minds, but it should be shorter and richer.

The film features a lot of special guests talking about the bizarre, often antagonistic, sometimes tragic, always entertaining life and myth of Jeff Lint, from a wide cross-section of the arts – writers, musicians, comedians. Alan Moore in particular, as always, has a lot of fascinating things to say about Jeff Lint. How did everyone come to be involved?

SA: I knew Alan, Andrew O’Neill, Jeff Vandermeer and Vessel. Stewart Lee was a fan of the book, had mentioned it to Alan, not realizing Alan already knew me personally, so Alan connected me and Stewart. I’d met Josie Long when I was performing at Andrew’s club. Later on Alan put her in Dodgem Logic magazine, in fact a lot of people in the film also ended up in DL. I’d heard about the band Seven Inch Stitch because they put out albums full of songs based on Jeff Lint story titles – genuinely. So of course I got in touch with them and they turned out to be incredibly funny, like a Texan Laurel & Hardy. They’re golden actually. Almost everyone I asked made themselves available to be filmed. I would have liked Jeffrey Ford, who I’d met a few times and who’s a Caterer fan, but it didn’t happen. Also Mike Moorcock who I know well, and who’s about the most generous person on the planet, but that never worked out logistically. But anyway, the people I interviewed came out with great stuff, using my books as a springboard to go out into their own ideas which I wouldn’t have thought of.

At the Brighton premiere of the film, you mentioned that while Lint covers a lot of ground in a wide-reaching way, you have a few books that are as wide but also go deeper than Lint. Care to talk about those? Do you have any favourites of what you’ve written?

SA: Novahead goes a lot deeper than Lint – even the other Lint-related book, And Your Point Is?, which is better satire, goes deeper than Lint. So do the Accomplice books. And there’s a novella I wrote called Shamanspace which has almost no jokes in at all, just satire and meaning. There’s so much meaning and resentment there’s no room for anything else. At the total opposite extreme there’s The Inflatable Volunteer, which is all stupid jokes and barely any meaning at all. Lint falls somewhere in between. My favourites of mine at the moment are the most recent, Novahead and Rebel At The End Of Time. Rebel At The End Of Time is my other experience of writing something set in another writer’s world [Rebel is set in Michael Moorcock’s End Of Time universe; we had been discussing the issue of Alan Moore’s Tom Strong comic that Steve wrote], which felt like a perfect fit. A lot of Moorcock’s original characters are in it, plus a lot of my own. I didn’t mess with his world or bend my own characters to fit – it just worked. Werther de Goethe is maybe a bit more thorough in his darkness, but that’s it. It occurs before Moorcock’s Dancers At The End Of Time, in such a way that Dancers occasionally refers back to events in Rebel. It’s very, very rich visually and in idea-shapes. It was finished in 2007, and was finally published in 2011. It’s frustrating because some of the predictive stuff has ended up just looking like commentary.

And my standard last question – say you’ve stolen a space shuttle and are flying it directly into the sun, for whatever reason. What would the soundtrack be?

SA: The least epic and most sarcastic thing I can think of in that circumstance would be ‘Angela (Theme from Taxi)’ by Bob James.