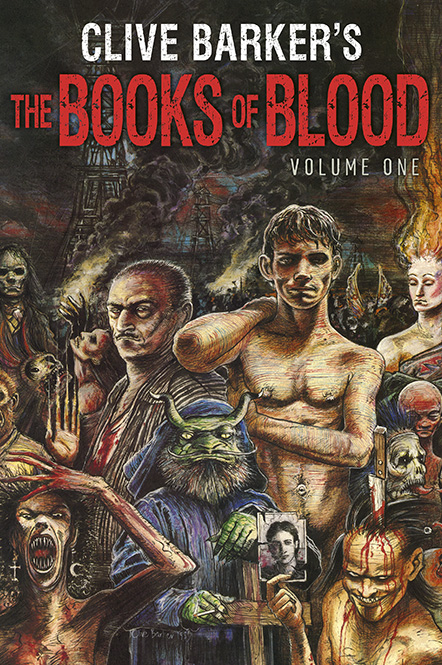

When Clive Barker arrived on the horror fiction scene in the early ’80s the effect was seismic and instantaneous. His Books Of Blood collections pointed towards a myriad of previously unexplored directions for fantastic fiction, and went on to influence – consciously and unconsciously – pretty much every practitioner that came after. Barker took a genre that was becoming boringly familiar and injected it with heavy doses of irony, proletarian anger, humour and raw sensual threat that, while hinted at by his predecessors, had never been so openly and seductively explored. His first feature film, Hellraiser, 30 years old this month, was similarly game changing. The film pulled all the familiar Barker obsessions together into one glowering, eroticised whole and provided scenes of mayhem so shockingly realised and brutally explicit that the whole world took notice, making the film a massive commercial and critical success.

Stephen Thrower, a member of post-industrial pioneers Coil at about the time that The Books Of Blood were released, is a horror fan and expert of long-standing. He has released books on the cinema of Lucio Fulci and Jesus Franco and is responsible for Nightmare USA, probably the most in depth account of the rise of American exploitation and horror cinema. Stephen’s relationship with Clive Barker’s work goes back to the early ’80s when Coil produced an unreleased soundtrack for Barker’s Hellraiser film, and his familiarity with the genre makes him the perfect person to talk with about Barker’s influence and legacy.

When did you and Clive Barker first meet?

I met him in either 1984 or early 1985. I was doing a bit of work at Forbidden Planet at the time, when it was a smaller shop just round the corner from Denmark Street. I was doing a little bit of part time work behind the counter there and I’d read the Books Of Blood, so I knew what Clive Barker looked like when he came into the shop. The great thing about working at Forbidden Planet was that it had the kind of atmosphere where you could hang out and chat with people. I said hello and said how fantastic I thought some of the stories in Books Of Blood were. ‘Pig Blood Blues’ was the one I was raving about at the time, the one about a sex-cult in a boy’s borstal.

So we got talking about that and then went out for a drink and eventually I said ‘you should have a listen to this group I’m playing with…’, which was Coil. It must have been ’85 because by that time I was recording Scatology with them. I played him some of Scatology and he was just bowled over, absolutely amazed. I think the tracks he was particularly keen on where ‘Cathedral in Flames’ and ‘The Sewage Workers Birthday Party’ But yes, he was really taken with the music and I suggested he come over and meet Johnn (Balance) and Sleazy (Christopherson).

So was he a regular visitor?

No, as far as I can remember he came to the house once and then most of our meetings afterwards were in town. He spent an evening at Beverly road which was Chiswick way – chez Coil at the time. So, yeah, he had a really enjoyable evening in with us and got on very well with Sleazy in particular, I think.

When was the suggestion made about Coil doing a Hellraiser soundtrack?

He was interested in us pretty early on. He showed us the Hellbound Heart when it was an unpublished novella he’d only just written. He said he was interested immediately, and there was a real strike-while-the-iron’s-hot sort of feeling. He was really into the music. He’d just recently produced the script and had said pretty much straight off the bat, ‘I’m going to be directing this myself, I’d like you to do the music.’

The rumour has it that he was fed some magazines by Sleazy that directly influenced the aesthetic of the Cenobites. Can you confrm or deny that?

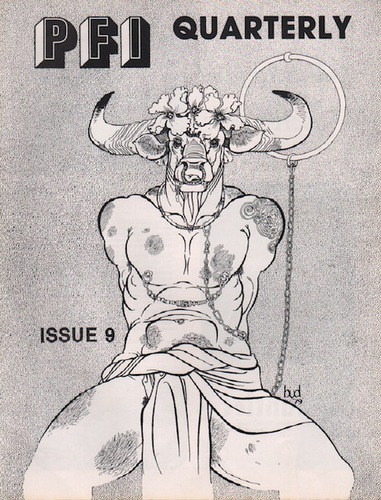

Oh absoutely. When he came to Beverly road Sleazy had a collection of magazines called PFIQ, which stood for Piercing Fans International Quarterly. I think the magazine dated from the very early ’80s until about ’85, and the content was the kind that people became a lot more familiar with in the ’90s, but at the time was completely underground. There was no overground, mainstream, fashionable acceptance of that material. It was very extreme sado masochistic piercing and body modification, to quite shocking extremes in some cases. The kind of images you’d see in there were of things like penile bifurcation, where people slice their cocks from top to bottom and then flay them apart. There was scarring and scarification and extreme crushing and body modification – tightening of corsets and metal bands and things – all sorts of fun and games with genitals male and female. I guess when Clive came over the conversation turned to pornography, and I don’t quite remember how it came that the PFIQs came out on the coffee table, but they did and Clive was absolutely bowled over. I think he spent a fascinated half an hour quietly looking through them. He disappeared into a little wormhole for a while.

So how did the work on Hellraiser proceed?

Oncce Clive had said that he wanted us to do it we sat with him and had a conversation about exactly what he was looking for. We talked about what kind of film music we were really impressed by, and there were two examples which he talked about, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Carrie. Those are two very different soundworlds.

About as different as you can get…

He was interested in Texas Chain Saw… from the point of view of its ability to instil fear and unease. Pino Donaggio wrote the music to Carrie and it’s got a very romantic quality; very beautiful and melodic and melancholic. So what he was essentially saying was ‘I love extreme sound and I love rich melody and orchestration’. We said ‘No problem, we can handle both of those’. I think Scatology had already come out and we were probably already starting work on what became Horse Rotorvator. Sleazy, when he’d been in Psychic TV had been working with string sections. We had people like Billy McGee and the string players for Marc Almond’s group as friends, so we knew that if we wrote something on samplers and electronics we could then say to out friends ‘now we need to work out a string part for this’. We started work but the plug was pulled before we got any further than the elecronics side of it, so the music that we actually had completed by the time they changed their minds was basically the electronic realisations that were awaiting orchestration.

So when I listen the Coil’s Hellraiser soundtrack it’s basically an unfinished record?

Yeah. It’s a little bit more than a demo but not really a finished score. If you listen to Horse Rotovator which is the album that came next and you listen to a track like ‘Ostia’, which has got fairly elaborate interactions between the string section and the electronics, that’s really the route down which the Hellraiser music would have gone as well.

Did your dissapointment about not being able to do the soundtrack colour your appreciation of the film when it came out?

To be honest I don’t see how it can not. The production company had their own composer waiting in the wings and when Clive got into difficulties with Hellraiser because there wasn’t enough money to shoot the effects that he wanted to achieve he turned to the producers and showed them a rough cut of the effects scenes. As far as I understand the conversation went something like ‘Oh we didn’t think this was going to be as commercial as it is. Re-shoot those effects scenes and here’s some more money. One stipulation, we want our man to do the score.’ I think Christopher Young was a protegee there and was evidently the next big thing as far as they were concerned. I suppose they were looking in a very hard nosed way and going ‘what hit records have these guys made?’ Clive took a pragmatic decision and I should think was extremely embarrassed about the situation. Although at the time we were all quite unhappy about it, I can sort of see the bind he was in.

What do you think of Hellraiser now?

There are certain things I like about it and certain things I don’t like about it. Now that the dust has settled without past history colouring everything, I still think it’s quite a flawed film and it’s got an extremely unstable tone to it, but at the same time it’s delivering some genuinely transgressive and shocking imagery and startling ideas about how to present that imagery as well. But it’s not just shock imagery, there’s a relish in the dark excitement of it. You’re not meant to be terrified exactly. More fascinated and terrified at the same time

Can you remember the impact that Clive Barker first had?

Books Of Blood was enormous. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that Clive was the literary discovery of the ’80s for fantasy and horror fiction. There were six volumes and every single story was firing off in a different direction. One story would be a classic monster movie with a bizarre sexual undertow, the next story would be a surrealistic fantasia about a city made of people who tie themselves together and walk as a giants across the hills. Bizarre imagery, fantastic dreamlike stories, gruesome stories. He seemed to have equal facility in all those different styles.

What is his most lasting influence on the genre?

In a funny kind of way I think the genre might not have picked up the challenge of Clive’s work. He didn’t end up influencing as many people as one would have hoped. Certainly around the time Books Of Blood arrived and Clive first started making a name for himself – directing Hellraiser and then on to direct Nightbreed – there was a tendency in the horror genre to downplay horror and play it for laughs. To turn it into an easily digestible experience. There was no real danger or confrontation going on. So in a way Clive arrived at a time when the genre was starting to slump. When I look now the one person who comes to mind who does feel very simpatico is Guillermo Del Toro. I think The Devil’s Backbone feels more akin to Clive than anything else I can think of and Cronos was another one. That feels like it could have come from The Books Of Blood. In terms of the style and the richness of the pallete from which he works, I think that’s something he shares with Clive.

Are you a fan of any other Barker film Adaptations?

Funnily enough I do like Rawhead Rex. A lot of people don’t like that one and it got a bad rap. It’s got quite a few things wrong with it, it has to be said. The monster is cross-eyed for a start which slightly undercuts the threat level. But at the same time it’s a really gutsy monster movie with some really quite shocking scenes. Any movie that features a monster pissing over a priest has to be worth something!