From the very opening scene, a single shot lasting some six or seven minutes, Son Of Saul propels the audience into the sclerotic heart of darkness that is Auschwitz-Birkenau. The chaos and torment is pitched at a level that grips by the throat in a chokehold that seldom eases over the course of the film. We follow a man into the sparse changing rooms, performing his duties as another load of victims are herded into the communal ‘showers’ followed by shouted promises of “soup and bread” awaiting them when they come out. The doors are locked shut and it’s then that the hammering starts. A frantic hammering on the steel door and walls in a deranging timpani as those inside grasp the horrific reality of the gas chamber. All the while, the man we have followed props himself against the door, his face scant of emotion but eyes full of the awareness that this is a fate he is only ever able to delay.

It is as devastating an opening ten minutes as any film is likely to deliver; a cacophonous encapsulation of terror that the rest of the film, for better or worse, doesn’t quite achieve again.

Son Of Saul is the debut feature from Hungarian director Laszlo Nemes, and won the Grand Prix at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, as well as the Best Foreign Language Film at the 2016 Academy Awards. The film tells the story of Saul Auslander over the course of a day-and-a-half in Auschwitz concentration camp during the Second World War. Saul is a member of the Sonderkommando, a group of young, fit and able men who were singled out as a group to perform certain duties, such as the hauling away of corpses and scrubbing the gas chambers clean after each extermination. In return for such grisly complicity their own deaths were postponed.

It is while performing such a task, that Saul becomes fixated on providing a proper burial for a young boy who he takes to be his son (although the veracity of this is left ambiguous), proceeding to persuade the doctor away from conducting an autopsy and corral purported rabbi figures into facilitating this symbolic demand for dignity in the face of so much dehumanising indignity.

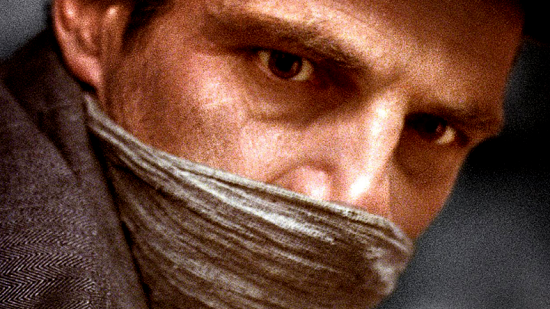

Throughout the entirety of the film we never leave Saul for a moment. We perch on his shoulder as his silent conscience, fix behind like his shadow, and confront him face-on as though trying to provoke him out of the monotone suite of expressions that capture his stoic response to such a horrifying reality.

With the cinematographic preference for shallow shots and soft focusing, the violence and despair largely occurs on a peripheral level to Saul, in sight but always somewhat blurred, as though Nemes is forcing the audience to become attuned to the same benumbed and desensitised frequency that Saul is operating on. In terms of this choice of style, one can’t help but think of the newly-released Victoria which adopts a similarly ambitious tracking perspective, as well as, at times, the frenzied and reckless abandon of the Russian film Hard To Be A God.

Where the film is perhaps most successful is in its sound design, which in light of the constrained visual impact, is accentuated in importance and weight. There is at times a whirlpool of different dialogues and voices, a cavalcade of sounds, screams and hushed whispers that, at the level of sensation at least, serve to thread together a deep and thoroughly convincing experiential tapestry.

The weight of subject matter though should not render objectivity obsolete or dilute criticism, and It is hard not to feel that the more intense the subject – and as a subject they don’t come more intense than the Holocaust – the more there is a propensity for the contagious chorus of benevolent applause to swell around critical communities. Son Of Saul is a good film undoubtedly, and as a stylistic choice to make, Nemes deserves ample credit for being as bold and brave as perhaps any debut film director before him. But is it a great film, on a par with something like Elim Klimov’s Come And See? Almost certainly not.

Not at any point are you exposed to the true essence or the ‘banality’ of evil in the same detached and abstract way as in Klimov’s masterpiece. There are indeed scenes of sledgehammer force in Nemes’ work – the opening scene as has already been highlighted, and the scene depicting Jews being shot dead into open pits which is rather like stepping into Pieter Bruegel’s ‘Triumph of the Death’ painting. But often the most subtle allusions and things left unseen deliver the deepest and most effective blow to the senses, and in this respect the film falls shorter than it really should.

The drama of the film doesn’t feel like it’s built on a sturdy enough foundation of the lived experience of Auschwitz. The director fails to really capture the incidental details that make the writings of Primo Levi so fascinatingly vivid. Recounting having to sleep two-to-a-bunk, top-to-tail in If This Is A Man, Levi describes how everyone in the barracks tries to ensure they are not the unfortunate one who fills the slop bucket to the brim since then they must take it outside, inevitably spilling some of the contents over their feet in the process. He remarks, with a grim but sardonic touch of humour, that the only person less fortunate in this situation is the one who has to share their bunk with him.

It is this kind of minor detail that can prove, if done well, both resonant and illuminating of the true experience, and that is sadly lacking in this film. There is the nagging sense the film leaves you with, that by favouring the stylistic elements over the substance, it is ultimately less than the sum of its parts. There are points at which it seems close to becoming a vehicle for showcasing the sensational, that while ordinarily of no consequence, in a film about the Holocaust is at risk of being troublesome. By the end, the struggle and strain of the protagonist almost becomes reminiscent of The Revenant, another film that eschewed emotional substance in favour of style and sensation.

It is said of panaceas such as anti-depressants, that the negative side effects patients experience engender in them a conviction that the drugs are working and hence they must be ‘getting better’. So it is that while those who view Son Of Saul will almost certainly come away feeling drained, devastated, and despondent, it should be borne in mind that these are emotions mandated by the horror and intensity of the subject matter and should not be attributed, at least not over-indulgently, to the success of the film itself at documenting the events at a particularly profound level.