John Eldridge died of tuberculosis in 1962 just a few weeks’ shy of his 45th birthday. For much of his life he’d been involved in the British film industry and yet, today, his name would barely register with even the most fervent of cinemagoers. He started out as an assistant editor whilst still in his early 20s and first made an impact directing propaganda films during World War II, oftentimes in collaboration with the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas. During peacetime he continued to ply his trade in documentaries – to greatest effect on the Edinburgh ‘city symphony’ Waverley Steps – whilst slowly shifting into features. As director he helmed a trio of likeable Ealing-esque comedies (Brandy for the Parson, Laxdale Hall and Conflict of Wings), but was arguably doing the more interesting work as a screenwriter. He penned the spiv noir of Pool of London, a bunch of charming little ventures for the Children’s Film Foundation and the fondly-remembered Peter Sellers flick The Smallest Show on Earth. His final assignment was among his finest and still ranks as one of the more nuanced portraits of youth to be produced in this country: 1962’s Some People.

The film came from fairly inauspicious beginnings. Its producer, James Archibald, worked almost exclusively in the documentary field (Some People would represent his sole excursion into straight fiction) and throughout his career would put together promotional items for the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Scheme. These unassuming miniatures cropped up intermittently throughout the sixties and seventies and were generally well-meaning, occasionally dramatized affairs with titles like In Search of Opportunity and When You’re Young. None of them are particularly notable nowadays (though a very young Jane Asher appeared in one, 1960’s Design for Living), but then none of them had the ambition of Some People. You see, the 1962 feature was also intended to promote the scheme – which, for those in the dark, sets out to help Britain’s youth by improving their employability, life experiences and physical fitness – though Eldridge used it as a mere jumping-off point. In his hands Some People is a snapshot of a very particular era first, promotional tool second.

British cinema during the early 60s was going through a transitional phase thanks to the input and influence of the ‘Free Cinema’ movement and the theatre’s ‘Angry Young Men’. Whereas representations of youth in 1952 could be summed up by the scaremongering juvenile delinquent pic Cosh Boy (the first homegrown ‘X’-certificate movie), by 1962 more sympathetic portraits had begun to emerge. This was the time of Tom Courtenay’s Borstal boy in The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner and Rita Tushingham’s pregnant teen in A Taste of Honey, characters who have since become figureheads of the British New Wave. The production company behind Some People, Vic Films, was heavily involved in this period, funding John Schlesinger’s A Kind of Loving and Billy Liar among others, and that seems to have had an effect. The cast is made up of mostly unknowns, the juvenile delinquents at its centre are treated with sensitivity and the entire production was filmed on location, in this case in a Bristol complete with authentic regional accents.

To be fair, the trio of lads who make up Some People’s main characters aren’t really delinquents. They’re at an age where they chain smoke but have yet to take a real interest in booze. Their passion is for their motorbikes, though that particular pleasure is denied them following a bit of tom-foolery under the Clifton Suspension Bridge. (Just one of the many refreshing location choices at a time when the British film industry was split almost solely between London and grim portrayals of the North.) Thus the boredom sets in, and the petty behaviour, or at least until Kenneth More’s benign cardiganned choirmaster offers them a potential outlet: the use of the church hall as a place where they can bang out a few tunes, one of them being more than proficient on the piano and all three owning guitars. Such a description potentially gives the whiff of some ‘let’s put on a show’ musical (especially with the presence of kindly Kenneth More), but this couldn’t be further from the truth. The gang aren’t working towards putting on a gig or cutting a single; they’re just hanging out and killing a bit of time. Indeed, Some People is at its best when it simply hangs out with them: a single-take stroll around a shopping centre than sounds entirely ad-libbed; a quiet chat down the pub between father and son.

Had the film been made two years later it would likely have been very different. Some People pre-dates Beatlemania and A Hard Day’s Night and therefore comes from a time when the British pop movie was of a quainter, quieter variety. Whereas the US instigated the trend with Rock Around the Clock in 1956, our first foray into big screen rock ‘n’ roll came with The Tommy Steele Story the following year. Shortly afterwards we had the likes of Rock You Sinners, The Golden Disc and a spin-off movie from the BBC’s The 6.5 Special, but if you had a few hits under your belt and were hoping to make the transition into cinemas then you tended to get lightweight comedy musicals. Adam Faith, for example, made What a Whopper, a farcical Loch Ness Monster tale co-starring Sid James and Spike Milligan. Billy Fury and Helen Shapiro, meanwhile, acted for a very young Michael Winner in Play It Cool. The energy and invention that typified A Hard Day’s Night simply didn’t seem like a possibility.

Of course, the music was much quainter too. The kids in Some People seem to be channelling The Shadows more than the most, right down to the fancy footwork. (The title song, incidentally, would be covered by former Shadow Jet Harris shortly after the film’s release.) In reality it was Bristol-based band the Eagles providing the tunes with the help of Valerie Mountain on vocals, another Bristolian thus adding to that authenticity. She’s lip-synched by Angela Douglas, though the rest of the onscreen band had musical credentials. Lead actor Ray Brooks, who plays Johnnie, learned to play guitar whilst a teenage redcoat at Butlins and was very almost signed by Andrew Loog Oldham. Drummer Frankie Dymon Jr, who would later venture into political activism, later recorded a Black Power-influenced album entitled Let It Out: Poems In Words And Music. (The character’s ethnicity is pleasingly uncommented on throughout.) And David Hemmings, playing Bert, had first found fame as a child opera star for Benjamin Britten. He would also make an LP with the Byrds in 1967 by the name of David Hemmings Happens. By that point he was one of the decade’s fully-fledged stars thanks to his appearance in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup. In fact, seeing the baby-faced Hemmings in Some People only goes to show how far off this all was. As said, the film comes from a different era – it feels as though it’s on the cusp of something and that makes for fascinating viewing.

In his autobiography, Learning My Lines, Brooks recalls a Sunday morning listening to Radio 2 during which time Some People’s title tune is played. Brian Matthew, host of Sounds Of The Sixties, talks about the song, the film, Valerie Mountain and the Eagles, and David Hemmings. But he doesn’t mention Brooks and this appears to sting a little: “What about me? I screamed in my head. But no – airbrushed out, unrecognisable, not worth mentioning, ego sunk.” To be fair to the actor it’s not as though Some People was his only major role. He subsequently appeared in Ken Loach’s Cathy Come Home, did plenty of television including a two-year stint on EastEnders, and was the narrator of children’s favourites Mr Benn and King Rollo. Perhaps not Hemmings-alike stardom, but it’s been a solid career nevertheless. Furthermore, it’s probably safe to say that Some People itself is the real recipient of the airbrush. The film has gradually slipped into obscurity since its initial release, barely cropping up on television (the most recent was on satellite channel Bravo during the mid-90s) and never appearing on VHS or DVD.

In part, this is likely to down to the unassuming nature. Some People refuses to try as hard as some of its contemporaries in presenting a more ordinary walk of life on screen. There’s no fuss to be made about the characters it’s portraying or the times they live in. As such the details are allowed to breathe: Anneke Wills wearing her jeans in the bath so as to get them sufficiently tight; Angela Douglas at work in a cigarette factory; the biker fashions and the cheeky, knowing dialogue. The decade would arguably produce more authentic portraits of British youth as the years progressed (John Fletcher’s all-improvised 1966 short Paddy’s in the Carsey and Barney Platts-Mills’ Bronco Bullfrog stand out in that crowd), though nothing quite compares from this very particular period. In fact, that may very well be the other reason for its obscurity. Some People resides in a limbo somewhere between the teenage years as documented in Colin MacInnes’ Absolute Beginners (first published in 1959) and the over-exposed ‘Swinging’ sixties as defined by Time magazine in 1966. Its era has yet to become a source of fascination or nostalgia – it’s either too early or too late for that – but then that only makes it all the more intriguing and ripe for reappraisal.

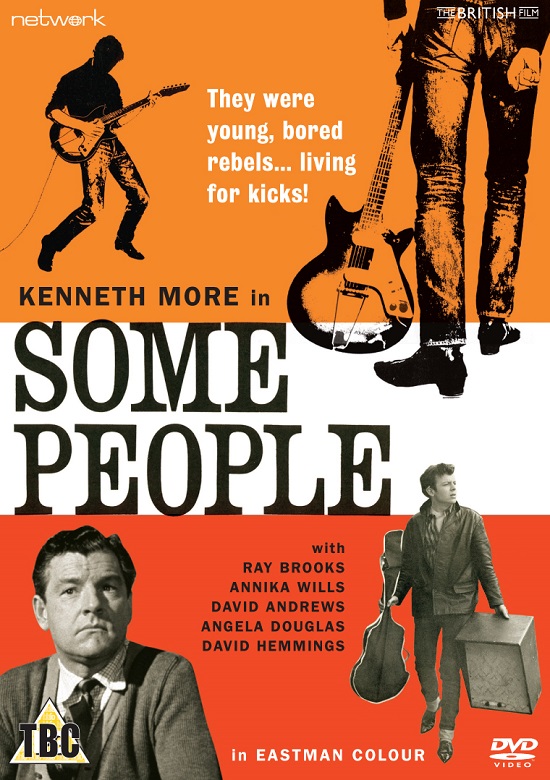

Some People will make its long-awaited DVD debut on the 20th of May courtesy of Network.