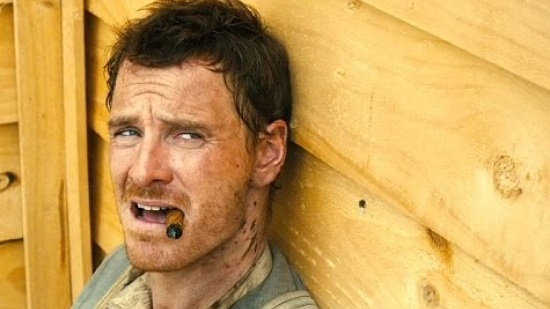

Visual arts were Scottish director John Maclean’s first love, and he speaks of his time in the much-loved Beta Band with the affectionate and bemused tone of someone who is genuinely surprised that an experiment actually worked out. Maclean wasted no time putting himself in charge of the band’s weirdly fascinating promo videos, and with his new technical skills in the bag, two short films followed the band’s demise. Man on a Motorcycle (2009) was famously shot on a camera phone and starred Michael Fassbender as a motorcycle courier at the edge. (Budding filmmakers with tiny budgets take note: it’s not actually Fassbender until he takes off the helmet). The more technical and witty, but still micro-budget Pitch Black Heist followed in 2011, again starring Fassbender, making Maclean’s first feature-length outing, Slow West, his third collaboration with the award-winning actor.

Fassbender’s commitment helped to ensure Slow West got made in the first place, and for that we should all be very thankful. The pleasingly large Screen 1 at Manchester’s new contemporary arts centre HOME, with its crisp visuals and sound, does technical justice to Maclean’s contemporary Western, the grand vistas, rich pallet and perspective tricks, and the more intimate acts of tenderness and violence. At a post-screening Q&A, the director proves affable, and open about his techniques, his cinematic imagination and influence, and even his auteur’s naiveté – though the picture he’s produced betrays next to nothing of the latter.

Our hero in Slow West is Jay Cavendish (played by Kody Smit-McPhee), a doe-eyed but dogged Scottish teenager on a trek to the American West to reunite with his lost love, Rose (Caren Pistorius). As he confronts the lethal wilderness, he is happened upon by Silas Selleck (Fassbender), a shrewd enigmatic frontiersman who appoints himself as Jay’s guide, for a fee. Soon afterwards, Selleck’s discovery of a WANTED poster for Rose and her father, complete with a hefty reward, shifts our POV, and all dramatic irony, in Selleck’s favour, as Jay unwittingly leads Selleck to his lucrative dead-or-alive confrontation. Adding further tension, the unlikely pair are themselves tracked by a rag-tag band of frontier survivors, all with bounty dollar signs in their eyes (and led by a spectacularly camp, charismatic and conniving Ben Mendelsohn).

Jay has been propelled into the beautiful, murderous frontier by his conviction that Rose will be waiting for him. The tragedy of the belief moves the narrative in various touching ways, but the moral conundrum of the journey falls squarely at Selleck’s boots. It’s here that Maclean most closely references the Western genre as the film grapples with the usefulness of a moral code that can’t help a soul to survive in a landscape of bones and tricksters and bounty hunters. The untangling of Selleck’s dilemma and its backdrop is an intense pleasure to watch – characters in perfect states of parallel and disarray; short, sharp and sometimes hilarious acts of violence; strange self-made Americans living feral lives out in the vastness; glimpses of a displaced and brutalised indigenous people.

Music and words are as impactful as guns and arrows. Jay happens on three Congolese musicians playing music with a rhythmical chant structure that is unmistakeably of that continent. Jay unexpectedly converses with them in fluent French. It’s a beautiful and disarming encounter, reminding us that beyond the edges of the film the upheavals of colonialism are already well underway. Almost all of the characters speak with unselfconscious adage-like phrasing, Maclean confirming that his script was ‘distilled’ so that each line might stand poetically alone. The Celticness of the leads somehow helps this to make sense, even as the film itself references the familiar Americana of McCabe and Mrs Miller, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, or Clint Eastwood himself, via Selleck’s ever-present cigar.

You might guess that with a musician for a director the score would be the ambitious centrepiece, but it’s cautious and touchingly spare (and composed by Jed Kurzel of The Snowtown Murders and The Babadook). Maclean is happy to let us listen to the land – rain, river, storm, trees, horses, gunshots on the wind, and the incredible recurring image of the night sky that makes no sound at all but is only there to be marvelled at, and the constellations named. Maclean’s pre-production experiences on a Colorado ranch made the director realise ‘what a huge part of America the sky is.’ It’s all the more impressive to know that Slow West was filmed in New Zealand for around three million quid, putting that most photogenic of countrysides to work to recreate the breath-taking plains, vaulted skies and haunted woodlands where America set out to discover its limits. Digital filming has given Maclean’s film a dream-like quality, but the complicated and brilliant dénouement of his story feels painfully real enough.

Slow West is in cinemas now