Simon Pegg is a man. A ruddy bloody bloke. When he greets me in his hotel he doesn’t smell of cinnamon or have an unnatural tan like films stars usually do. He’s not even doing the thing when they sit there in carefully ripped $3,000 joggers and ‘I’m just like you’ casually scrawled across their face. Simon Pegg is a massive, über fanbase-having film and television icon, yet he’s just sat there like a bloody man wearing clothes a man would wear.

Instantly the genesis of characters he created and played in Spaced and Shaun Of The Dead appear in his mannerisms and lingo, which is perhaps why there’s an unnerving sense that I already know him. After checking to see if I’m in the right room, I sit down. After explaining that the Quietus sent me here because we’re both called Simon, we sit in silence for around 15 seconds, could have been more, before I ask about his pants.

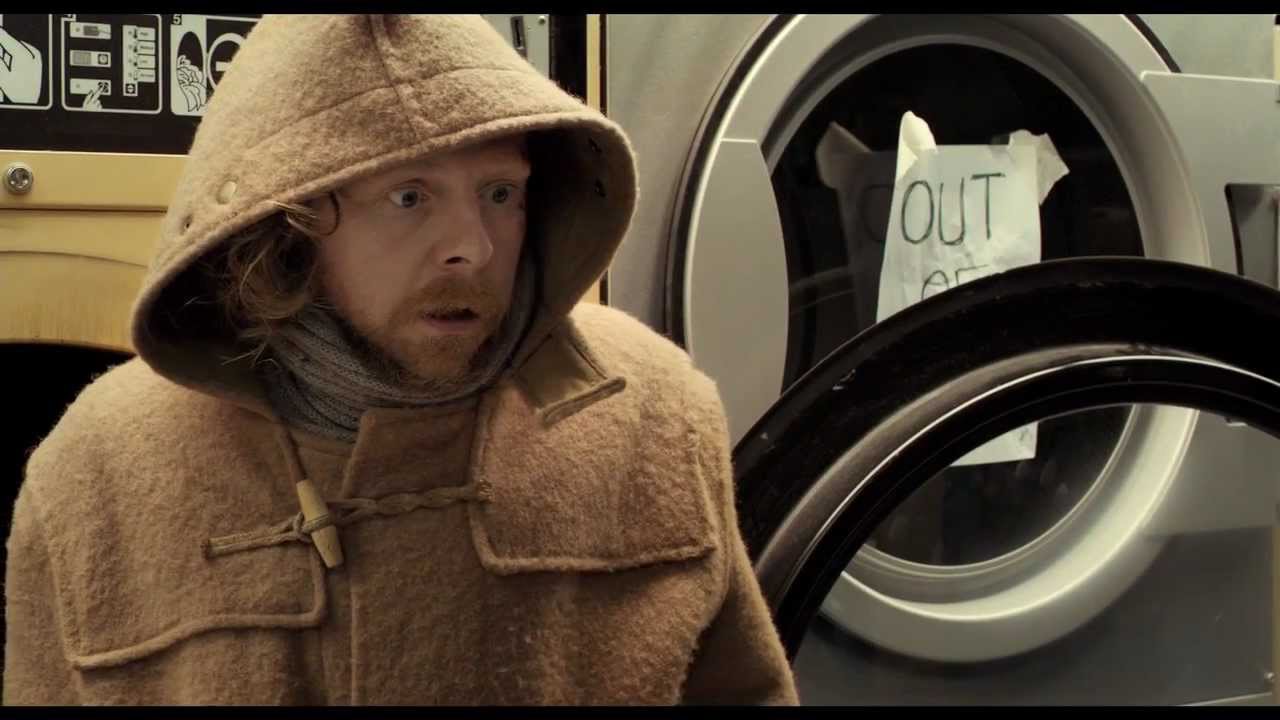

He’s promoting his new movie A Fantastic Fear Of Everything, written by Kula Shaker frontman Crispian Mills and jointly helmed by Mills and music video director Chris Hopewell. Unfortunately it’s terrible: a wacky, would-be Ealing-style take on mental illness that can’t decide what genre it is, so fails on the tension and bombs on the laughs. He does spend most of the running time in a pair of dirty Y-fronts though. It’s the usual double-edged criticism hurled at Simon Pegg: why are you doing this when you’ve created such funny and successful projects? As if Delia Smith has somehow been conned into working at Wetherspoon.

Pegg is a self-made star who, along with Edgar Wright, built a comedy empire not by flashing his baby at tabloid photographers but with his hands (which are quite delicate) and brain (which is massive). Though it only lasted two series, Spaced set new standards of inventiveness from the confines of a lounge. Being about 18 when it first aired, I realise that I’m talking to the man who, along with Dave Lister, created around 60% of my casual lexicon, and am instantly and unexpectedly launched back on a rocket of nostalgia. Wait, I realise, he’s not just a man at all. He’s Simon fucking Pegg!

Is there anything funnier than a man in his pants?

Simon Pegg: It’s a comedy staple which underpins an essentially thoughtful and interesting and different kind of movie. But at the root of it is a man in his pants, which is the safety net.

Was the intention when you were doing Big Train to go into movies?

SP: No, I’ve thought about this, about what I wanted when I was doing Big Train. I’m not a particularly forward planning person, I never had a five-year plan. I was getting Spaced together at the time and was just sort of ambling along. I never thought for a second when I said about odd-numbered Star Trek movies being shit that I would end up being in an odd-numbered Star Trek movie less than ten years later.

Have you ever been tempted back into stand-up?

SP: I have occasionally. You can’t just walk back into stand-up because you have to get match fit, it requires you to be very sharp. It’s like extreme performing, the crystal meth of performing: you are validated on the spot there and then.

You keep your private life quiet, but every time you create something it seems extremely personal. Is it?

SP: My theory in terms of writing has always been write what you know and write with authority, because then it would be true. Even if there are coded elements of your true self in there. It doesn’t bother me being personal as long as it’s not my actual private life. That’s something I don’t feel has any relevance to my job. I see people introducing their baby to the world in fucking Hello! magazine or something. You fucking whores. Jesus.

I had this idea that everything you put on screen was smoke and mirrors, and you never read a comic book and you hated Star Wars.

SP: Yes, I’m a big fake. I often think I’m less of a geek than everyone thinks I am. I love science fiction, though sometimes I do prove myself wrong to a degree, because I do know ridiculous amounts about that kind of stuff. But I’m not a speccy, sand-in-your-face kid. I’m not that kind of nerd. People say Spaced was geeky, but it was also about people who liked to go clubbing and take ecstasy. It wasn’t just about that particular demographic.

Do you ever over-geek to appease the fanbase?

SP: No, because I don’t ever want to be untruthful. I also get frustrated with the notion of celebrity being that you have to be a certain thing, you have to stop liking the thing you’re in. I’ve always been honest about how I’m very excited to do the job I do and I get a real kick out of being in Star Trek because I like Star Trek. I’m not going to be all, "Whatever, it’s just another day at work with Tom Cruise." I’m like, "Fucking hell it’s Tom Cruise!"

You’ve worked with some pretty big names now. What has been your most surreal experience?

SP: Most surreal experience was the Paramount 100 year anniversary photograph which we shot in LA in February. They had a big group photo of 100 actors, directors and writers that had worked with Paramount over the last 100 years and it was like being in a waxwork museum that had come to life. It was most extraordinary. I was given access to this special day, but so were Mickey Rooney and Jerry Lewis and Kirk Douglas and Jack Nicholson and Steven Spielberg and George Clooney and Brad Pitt. Also, no assistants or partners were allowed in the room, so it was just the people. Peter Bogdanovich and Robert Evans and Scorsese and De Niro and Tom Cruise, Meryl Streep and Shirley Maclaine. I was thinking, "I’m from Gloucester!" It was oddly surreal.

Have you had any awkward moments after berating The Phantom Menace so publically?

SP: No, George Lucas doesn’t know who I am. I’ve worked for him on [animated series] Clone Wars, which I was happy to do. But I know Steven Spielberg now and it’s interesting to talk to him about stuff like that because George Lucas is his friend and he defends him, in so much as he’ll say, “They’re George’s films and he can do what he likes.”

You asked Steven Spielberg if he thought The Phantom Menace was shit?

SP: No, I could I think, but I wouldn’t want to put him in that position. I probably wouldn’t because it’s rude. I bring it up with Bard Bird, who directed MI [last year’s Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol], and he’s got… oh I don’t want to get anyone into trouble.

Every time you have something out there’s always tremendous expectation. Are you ever worried that’s going to haunt you?

SP: As long as I’m happy with it. Much is made of the product when it comes to art, when art is not a product it’s a process. The product is the result of art. It’s what you’re left with once it happens. A painting is a relic of what the process was. A film, even though it’s enjoyable in and of itself, is still evidence of something that took place. As long as I enjoyed the process and am happy with what I’ve done, I don’t really care what people think of it. It’s a joy if they like it because it means I can do more work. If something comes out, I’ve got to take it on the chin if people don’t like it. But if it’s something I’m proud of, if someone doesn’t like that, it’s not my problem.

Do you find that people enjoy the films you’ve done which you’ve written yourself, rather than projects you’ve just acted in?

SP: Yes, sometimes. There’s a core group out there who specifically like Shaun Of The Dead and Hot Fuzz and wish I’d stop doing films like Mission: Impossible and go and write another series of Spaced. But there’s probably a bigger audience who go to see the bigger stuff and have no idea who I am and what Shaun Of The Dead is. I want to keep everybody happy. If I did a film that turned out to be rubbish, and had a good time making it, I’d never regret doing that, even if it got slammed by the critics and audiences alike. If I make good friends and enjoy going to work every day, I’m never going to regret it.

How did the Three Flavours Cornetto Trilogy come about as an idea?

SP: It’s a very easy story to track. In Shaun Of The Dead, because they were both hungover on the morning of the zombie apocalypse, Shaun goes to the shop and we thought, what’s a good hangover cure? And Edgar said, “Cornetto. I always used to have a Cornetto when I was hungover.” Cut forward to the premiere party and Cornetto provide us with free ice cream. So we were writing Hot Fuzz and, in a very self-indulgent way I’m sure, we thought: let’s put a Cornetto in Hot Fuzz and we might get free ice creams again. It was that self-serving. So then when we were doing the press for Hot Fuzz, we were asked if these films were about ice creams, and Edgar said, “Yes, it’s Three Flavours Cornetto,” making a joke on Krzysztof Kieślowski. That stuck and it became the blood and ice cream trilogy.

Does accepting the trilogy idea make the next film seem unnecessarily final?

SP: It is a final part in this set of films. We always had the idea of doing this series of thematic sequels, and not like direct sequels, so Hot Fuzz wasn’t a continuation of Shaun Of The Dead, but it is thematically a sequel. And World’s End is the binding piece that will gather it all up as a trilogy. All three films are about the individual against the collective and, if you want to get really film theory about it, it’s the dialectic of evolution, devolution, revolution. So Shaun… is about evolution, because it’s not just about the emergence of a new species, it’s about someone becoming something. Hot Fuzz is about someone devolving into something less. It’s about Nicholas Angel becoming a thug because that’s what he has to do. And the revolution, you’ll see why when it comes out.

How much of this is your own imposed theorising?

SP: No, that’s us. The ice cream thing is imposed, the other stuff is conscious. We didn’t set out and go let’s make a film about da da da, it dawned on us though the making of it that our thought process has taken that kind of… that’s our journey with the film. And it is about our lives in a way. Shaun… was about growing up. Hot Fuzz we were feeling like we were being forced to be more mature, and with World’s End the idea was about becoming middle-aged and fighting that. So as a film student I can analyse my own work to find out what I was subconsciously going for with each film. You can look at any film and look at the subtext, look at what was going on in the filmmaker’s mind, what his preoccupations and concerns were at the time. I can track our films very clearly as to what we thinking about at the time.

What flavour is World’s End?

SP: This one has to be mint because I think that’s the last one. There are certain special edition Cornettos but it has to be. Shaun… was strawberry, Hot Fuzz was traditional regular – whatever that is, blue and white – and this one will be mint.

Is the final film in the trilogy the end of a working relationship?

SP: No, not at all. We’re friends first and foremost and I’ll work with both of them hopefully the rest of my career. All I want to do is work with the people I trust and love, and Edgar Wright and Nick Frost are most certainly those people.

A Fantastic Fear Of Everything opens in UK cinemas today.