"I’ve been there and I know / Lots of other ways…"

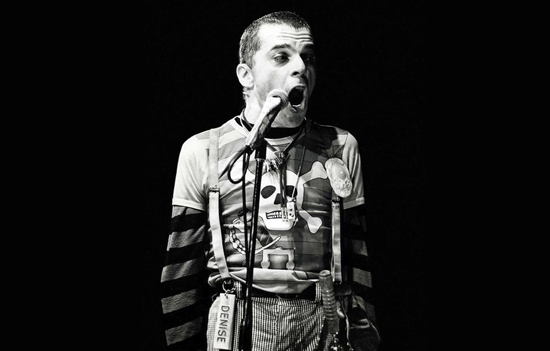

"There are a couple of ways to avoid death, one is to be magnificent." This is what Ian Dury, played (magnificently, as it happens) by Andy Serkis, urges us to strive for, eyes glittering with malevolence and magic, in the new biopic Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll – The Life Of Ian Dury. This must be why he remains immortal in our hearts and minds ten years after his death from cancer.

Even for those supposedly unacquainted with his musical legacy, this uber-articulate provocateur lives on, perennially robust, in our language, in the phrases he coined, and in the traits and idiosyncracies other artists – from John Lydon to Robbie Williams – have carefully studied, aped and made their own.

However, this film’s almost unwavering focus on Dury’s cruel side, rather than his matchless wordplay and years of timeless music with the Blockheads, is one that elicits mixed feelings amongst those who knew him best.

Director Mat Whitecross flings us into an exhilarating kamikaze riot of heightened colour, music-hall theatricality, a dazzling collage of fluorescent scrap-book titles (by Dury’s old art teacher and long-time friend Sir Peter Blake), fist-fights, flashbacks and, most importantly, funk, provided in the form of a freshly recorded soundtrack by the Blockheads themselves.

As joltingly thrilling as the music is, Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll is an exploration of Dury’s relationships with his son Baxter (who admits watching the film was like “being at a séance”) played with a feral sensitivity by Bill Milner, his wife Betty (Olivia Williams), his lover Denise (Naomie Harris) and his father Bill (Ray Winstone). But, with the exception of his song-writing partner Chaz Jankel, Dury’s relationship with the Blockheads is left largely untouched, even though he arguably spent more time with them than any of his family throughout that period. [Chaz received a BAFTA nomination for his excellent score and Serkis also go the nod for his portrayal of Dury.]

We see Dury bullying, taunting, suffering, hurting. A great deal of time is spent understandably (to a point) poring over our anti-hero’s disability, from the moment he contracted polio as a child in a swimming pool to his miserable years in a children’s home. There are moments of humour, flashes of excellence, pitch-perfect performances. The chaos, dirt, excitement and sweat is all there. But how do the Blockheads feel about the route the film takes? What emotions are stirred by seeing Dury so accurately invoked by Serkis? Why were most of the Blockheads mute in the film? And, on another tack, what do they think about the flourishing Facebook campaign to get ‘Spasticus Autisticus’ to the top of the venerable hit parade?

What were your thoughts on the slice of Ian’s life they chose to magnify in the film? It’s interesting to see what they concentrated on, classic biopic fare in a way.

Norman Watt Roy (bass): I found it all very… if I was a fan and I wanted to see a film about Ian Dury and the Blockheads, I want to come away and think, ‘Hey, that man was fucking clever with his words, he was a genius when it came to lyrics, and he made some great music with the band.’ But you come away thinking, ‘What a fucked up, messy life!’ it’s quite dark. I’d want to see his genius celebrated.

Also, I don’t think his personal relationships were interesting enough subject matter. Being called Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll, like the song, it should be a film about Ian and the Blockheads, and it really isn’t.

They’ve definitely gone for the literal translation of ‘Sex and Drugs’ but if the film introduces people to the music or remind them how much they loved it, that can only be a positive.

NWR: Exactly. And I think the acting is brilliant, Andy does a fantastic job though, I even said to him, "You’re brilliant, man." He really does play Ian very well. He’s let down by the aspects they’ve chosen to concentrate on, his early relationships. And the obligatory two-minute bed scene… I was like, "Oh…" I was cringing then, "Oh no!" That was embarrassing…

I want to see a film about Ian and the band and what it was really like, all the great stuff that he did. Some people will find it interesting I suppose. The acting saves it, I think.

Johnny Turnbull [guitar]: I think they chose, in the biopic way, to focus as everybody normally does on the fact he was a disabled, troubled soul who through adversity made good, and then made bad, and that’s basically their story. He could have had it all and kept it, but through one thing or another he kind of blew it in a way. Which we’re just beginning to see now, while you’re on the ride you don’t see much… you’re just on the ride going, "Wow! Wooo!" and then you see the bigger picture of what it could have been…

I’m thinking of specific things that I learned later on, like Davey Payne found out we had been offered to support Pink Floyd on a tour, which would have given us more than double glazing… you know? And Ian said something like, "No, I don’t wanna support those bastards." I don’t know the quote, something like that. So it went out of the window and it never really filtered through the ranks until later that we’d been offered anything like that.

And there were little things like, we tried to conquer America and several people blew it in big ways. He was one of them with his attitude towards the record company and people like that. Also Kosmo Vinyl blew it by kind of man-handling the head of the record company, "Where d’ya get that suit, mate?" and all that sort of thing. It was just uncouth, you don’t do that to record company bosses who are probably retiring to live next door to the head don of the Mafia, you know? You don’t do that, you don’t behave like that.

No. It sounds good in the annals of rock history, but…

JT: In hindsight you get a bit annoyed. Well, I do anyway when I’m sitting here without double-glazing, you know what I mean? Knowing that it could have been a bit more cushti, everyone could have been well looked after. But that wasn’t the way he wanted it.

You must feel the rest of the Blockheads could have been portrayed more as characters in the film?

JT: Definitely, yes. I’m reading Will Birch’s book at the moment which is quite a good read. He’s been researching it for the last 12-14 years, and he did speak with Ian in ’99 when he was first diagnosed, and everybody else. There’s a lot in that that could be gleaned for whoever writes the next script for a movie.

NWR: We don’t have any lines at all. Ian doesn’t even talk to the Blockheads, apart from Chaz and Davey (saxophonist Davey Payne, who actually doesn’t get much in the way of characterisation either, other than a couple of lines, some fights and a scene in which he nuts Chaz onstage). That was because we didn’t sign a contract that meant they could portray us however they liked though.

Chaz Jankel [composer, guitar, keyboards]: I suppose out of everyone in the Blockheads I’m the most involved in it, because in a way that story is much more applicable to me than the rest of the Blockheads, I mean, you’ve seen the movie and it really does deal with Ian’s personal relationships with Denise and Betty and myself, and also covers the last version of Kilburn and the High Roads, so there’s a lot of other issues on the agenda other than the Blockheads.

I was concerned they made (Ian’s girfriend) Denise come across like a groupie initially, it plays up to the received idea of the stock characters you’re supposed to find on the road, but I don’t know if that was really fair…

NWR: Yeah, Derek [Derek ‘The Draw’ Hussey, Ian’s friend and now the Blockheads’ frontman] was saying that. Denise was a lovely person and it wasn’t nothing like groupies.

I think there’s another film to be made that concentrates more on the Blockheads, the music, the Stiff years, his life up until the end.

CJ: Yes… I think there is, I think everyone is still recovering from making this movie, but yes, you’re right in as much as it ends at a halfway point in Ian’s life. Although in a way, that is our history, what you’re seeing there. If it wasn’t for Ian, none of this would have happened, so he is the legacy, the lifeblood of us.

The difficulty is, to make another movie, I’m not sure how much drama there is in there. You’d need some very clever writing, because at that point, after Spasticus, Ian took a lot of time off, it was kind of quite invisible, his lifestyle, it wasn’t quite as dramatic as what had happened in the past.

What happened towards the end of Ian’s life, making Mr Love Pants, that was quite dramatic and that was an amazing album, but I think it might go more into documentary land in that there wasn’t the obvious visual dramatic material to draw on, it was like Ian was doing a bit of acting, he then very sadly got cancer, so that would be the natural conclusion to this movie. There were some very fascinating details in it, but accurately what happened, if you were follow it through to the end, Ian passed away from cancer. So yes, there’s more to be told, but you’d have to really think about it quite carefully. I reckon it would be a harder movie to make.

JT: I’m looking forward to part two, part three! You don’t know what else they’ve got in store. They’ve done a good job with the period they’ve chosen. How many hours of filming have they got, how many angles have they got? Could they get another story out there even more gruesome or real? I don’t know, possibly they can. There’s lots of ways you can do it. They also filmed everything we did in the studio when we made the soundtrack. There’s a lot of material. I don’t know though. It’s early days. The film hasn’t even reached Scunthorpe yet…

Also the thing with the film that’s like…you know, is it a band or is it Ian Dury? Well, it was a band. Basically, he nicked Loving Awareness (a group initially set up by Radio Caroline’s Ronan O’Rahilly) lock, stock and barrel, and added Chaz and Davey. We were tight, we’d played together since ’66, Mickey and I, and with Norman since ’71. With Charley since whenever we got Charley, we were tight.

We were the perfect band for him, funky-rocky-jazzy-souly, and he was writing these strange, brilliant lyrics that no one had ventured to do before. Because of the idiom of the time that was kind of punky he went down that road a bit but he also went down the kind of funky dancey road. Chaz was quite funky, what Norman and Charley wanted to get cooking was great and me and Mickey were playing sort of Isley Brothers synths and guitars, and Davey was very unique with his approach to sax-playing, his performance on stage was huge in a small way – he just stood stock still when he wasn’t playing.

There’s clearly a good documentary to be made then. Maybe along the lines of the mighty Oil City Confidential (the new Julien Temple documentary on Dr Feelgood and Canvey Island).

JT: Yes, Norman and I certainly wish it was more about the music, but I think that’s a different story really. It would have to be made not in that biopic way, but an homage to what we did as Ian Dury and the Blockheads, to advance the British funk scene, or the British jazz-funk-rock whatever you want to call it! Because we did cover new ground but we were borrowing from whatever we liked all the time.

If someone was filming us when we recorded that radio show we did with Mark Lamarr on Radio 2, that would have made a great film. We’d all be choosing different records to play, Norman might have chosen a Charlie Parker record, Chaz chose Sly and the Family Stone and it was apparent what the influences were what set us off in the first place. And we were kind of able to tell the truth, in a way, about some of the aspects of Ian Dury and the Blockheads. I thought halfway through, "If they were filming this for Sky Arts, that’s the kind of programme I would like to see!"

We had the idea to do our own programme and get help from Phill (Jupitus) to narrate it, that might come to fruition, I don’t know, we’d need backing. Maybe music fans would prefer something like that to Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll. Also, what people forget is that Ian coined a lot of those phrases, like ‘Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll’, ‘Reasons To Be Cheerful’…

He put them in common parlance…

JT: Yes, he put them in common parlance! There’s your university education…

I went to the University of Life.

JT: Me too, I just put that on my Facebook page, I joined last night.

NWR: Oil City was great, I like things to be real.

CJ: I think the question to be asked really is would Ian have liked the movie?

I’m not just saying this, but that was my next question…

CJ: That was your next question? Oh! I think he would. He would have appreciated it as an important device, but he would have a bit concerned about the fact the movie tends to concentrate on his physical disability, and in all the time I worked with Ian, never once did he complain about his disability. We would talk about how he contracted it and what happened to his body, he was quite specific about the withering of his muscles and so forth, but he never complained, he was extremely stoic.

The movie does tend to make a big business out of it. Ian didn’t want to have it on display, although without that, well, it’s at the heart of that movie. So I would say that would be his … it’s hard, obviously I’m guessing, but I think that would have been one of the things he would have objected to. But at the same time, I think he would have thought Andy was awesome. He just read Ian so well.

He obviously completely immersed himself.

CJ: Absolutely. He’s quite happy go lucky… when you meet people like that you wouldn’t believe the depth there is to draw from, he immerses himself as you say in the character, he goes into it deeply and then afterwards he can’t remember the lines! After he’s let go he literally doesn’t remember.

Like coming out of a trance…

CJ: I suppose you’d have to do that, otherwise all the parts you play would stack up on you.

NWR: Andy totally immersed himself in the character, he wore the calliper for six months and by the end of it he was Ian.

[NB: There is a scene in which ‘Ian’ is swimming in his pool, and when he swims underwater, you are watching film of the real Ian Dury. When he pops back up out of the water, it is Andy again. After two viewings, it’s still hard to see the joins.]

It’s a great responsibility playing someone who existed, and who people hold in their hearts and have their own opinions on and memories of… I suppose you have to be as sincere in your portrayal as you can be. But it’s been said by some of the guys that perhaps he wasn’t actually mean enough in the film?

JT: At that time I suppose he hadn’t really blossomed into the Machiavellian character which we all know and hate… Ha! Love to hate, I mean…

CJ: I think they showed a bullying side in the film. There’s that example where he drops hashish in the gravy of Clive’s (his estranged wife Betty’s new man) meal when he goes round for Christmas dinner, and then he gets him stoned and then practically sticks a serving fork up his nostrils, and played the gang boss. I thought that was very cruel, there was that cruel side to Ian.

He once did the same thing to me, I was once round at his flat writing and he said, "Go on Chaz, turn the light out." And I was like, "Oh no…" He wouldn’t take no for an answer. I turned the light out and about 15 seconds later… I knew he was up to something, I could hear something and then it went absolutely quiet. And I saw he had a torch under his chin and he had a pair of devil’s horns, probably from a joke shop, but devil’s horns on his head, and he was staring into my eyes, I practically jumped out of my skin. And what about when he busts up the studio? He’s belligerent, and he’s quite prepared to do a lot of damage because he’s not getting his way.

I can’t remember who said afterwards, ‘Oh, he was ten times worse than that!’

CJ: Probably Mickey [Gallagher]. It could get pretty overbearing, as you know the only way I could deal with it was to go. And I did do that a couple of times, but at the same time, he was a lovable rogue and you ended up forgiving him.

JT: As Mickey said, “One beer, he was really entertaining. Two beers, he’d start to upset people. Three beers, it was unbearable.” Especially if he had it in for somebody, which he generally did. He liked to put people down verbally, and he was so good with the verbals, not many people could respond in an intelligent way because they were too upset by being offended by him! He’d put you down and make you feel tiny. I think they invented the term ‘control freak’ for him [laughs].

What did you think about how your character was portrayed, Chaz?

CJ: Well, I think, under the circumstances, he [Tom Hughes] did very well… some people have said he was a bit soft, but if I’m with an alpha male, I tend to back off and be quite soft, although in my day to day life, if I don’t have another alpha male to deal with, I’m probably stronger and more eloquent. But I’m a wolf in sheep’s clothing!

If I feel I’m just getting taken advantage of, I’ll say "That’s it" and I’ll put my foot down. I’ll be as broad-minded as the next person, but if I think someone is taking over and just using all of the oxygen in the room, I will say something.

I must say, there were odd moments and mannerisms when he was playing, or when he smiled, where I did think, "That’s really Chaz!"

CJ: You’re right, and I don’t know how he picked that up but I think when I was talking to him, he was watching and listening and there were little mannerisms he picked up on, I’m grateful for that because I think my character… because it was all about Ian, you know… I mean, I didn’t even get a costume change! They could have given me another shirt now and again, you know? Haha! I had the one trilby, the one jacket… I wasn’t that hard up, I did have another set of clothes… but joking aside Tom did very well.

What would you say they got particularly right in the film?

JT: Some of the one-liners are brilliant, the humour. When he says, "We’re arts and crafts…" (instead of ‘posh’ or middle class) that was very good.

Is that something he would actually say?

JT: Yeah, I think he got it from his mum. She was a lot posher than his dad. His mum would have said that, and then he passed that on to Baxter. They didn’t want to be known as too posh or too working class. Haha. “We’re arts and crafts…”

Was there anything you would have done differently? I know you mentioned the focus on the disability…

CJ: I would do, but I think you’d have to write a slightly different script. There was one moment in the movie where I think they lost the beat, and I mentioned it to the producer and he agreed. But I only realised afterwards, but when Ian is in his nouveau riche pad and he’s got his sycophants lounging around, after that they’re watching Spartacus, and just prior to that the young Baxter is walking around the house and he looks into a room and there’s Chaz playing the piano. Then I think I go into the room and say, "Ian, I’ve got a great riff" and he says, "Oh shut up". I think when I was playing the piano I should have been playing the ‘Hit Me’ riff. And if I’d done that it would have made sense… it would have tied up.

NWR: Fred ‘Spider’ Rowe is nowhere to be seen in the film, and he was Ian’s minder before the Sulphate Strangler. [The Strangler was the former roadie and speed freak who would become Baxter’s “psychedelic nanny” when Dury was absent, which was a great deal. “He gave me all the love he knew,” said Baxter. “He made me pie and chips every night, but sometimes he’d go to sleep for four days. Or I’d find scales and drug paraphernalia. I once found a girl asleep in the middle of our front room with a nosebleed. I got a bit feral, but there were enough people keeping an eye on it.”]

NWR: Then there’s all the poetic licence… There’s a famous story about Ian when he got punched by Omar Sharif, and I had to pull Omar off him, Ian ended up with a black eye. I took Ian home that night, all bloody, got him in the cab and Ian said to the driver, "’Ere, I’ve just been punched in the teeth by Omar Sharif!" And he was laughing, and the cab driver said, "Well, that’s the most expensive fist you’ll ever have in your mouth." In the film they’ve made it like he turns up to Betty’s house, and Betty’s boyfriend Clive, I’ve never heard of this Clive before, he says to Ian, "What’s with the black eye?" and then he says the "expensive fist" line himself. So they mixed it all up, they were interpreted wrong.

Another thing, Carol and Jenny Cotton worked with us, they looked after Ian’s girlfriends 24 hours a day, Carol rang me and said, "It’s nothing like how it was! Ian had about 20 or 30 girlfriends, in the film he only had Denise."

JT: They have taken liberties with poetic licence, I mean, they’re up to their knees in it. I think a lot of the stuff in the film they’ve taken from what we’ve said in interviews years ago and just mish-mashed it up and made the story they wanted to portray in that time period. So chronologically it’s completely wrong. The bit where Denise launches his calliper over the balcony after the argument… that happened in New Zealand as far as I remember, we did it when the new calliper arrived.

Tell me a bit about the score, Chaz.

CJ: It felt very natural, I’d written most of the songs and had done film-scoring before too. I was glad they came to me.

There were about ten songs that were licensed off Ian Dury and the Blockheads to be used in the movie so, I think around last March or April, we got together, the Blockheads, in Faraday Studios over in Charlton and in conjunction with Mat Whitecross the director we recorded the tracks in a way kind of directed by Mat because he was looking for a particular kind of performance, so in a way he almost acted as a kind of record producer on the day.

A lot of those tracks were used in the movie but it got a bit complex because the actors that were playing the Blockheads as young musicians were in fact musicians [including James Jagger, who plays a mute Johnny Turnbull], so when they were shooting scenes, these young actors were actually playing, and I’ve never actually asked for the sound mixes on the movie, what’s what, although I can tell on ‘Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick’, that’s definitely the Blockheads, and also ‘If I Was With A Woman’, and I would say the first part of ‘Sweet Gene Vincent’ near the end of the movie.

Was Mat going for a live effect?

CJ: Yeah, absolutely. He wanted it as fiery as possible, he didn’t want it to be too comfortable, he wanted it edgy. He was fired up and he got us fired up, I’m very pleased with the music in the movie.

The little snatches of jazz in the soundtrack, they were you guys with Andy Serkis on sax, I take it?

CJ: Yes. All the jazz cues… well, when I received the movie originally in its rough cut, Mat and Peter the editor had temped the movie with temporary music where they wanted that temperature. Basically in places they had put jazz to dovetail one scene to the next. They hadn’t licenced it, it was some Charlie Mingus, some Sonny Rollins, so I tried to match it with my own compositions jazz-wise. And I asked Dylan [Blockhead and jazz drummer Dylan Howe], we used to play together in the Chaz Jankel quartet, not on the road right now, and I asked Dylan if he knew of any good musicians, and he certainly did. He suggested the brilliant Steve Fishwick on trumpet and Chris Hill on bass, then there was me on piano, Andy Serkis on saxophone and Dylan on drums.

We rehearsed at Andy’s prior to the jazz date and then we went and recorded it at the Cow Shed studios, a great studio in Middleton Road, Bounds Green. Just one day of recording, and we also recorded a reggae tune and two Herbie Hancock-esque pieces that were in the party scene where Baxter first arrives, bewildered when he first goes to his dad’s house. Ian and Chaz are performing Sweet Gene Vincent for the first time. As Baxter enters the flat there’s some very loud, powerful Latin jazz, Hancock-esque, and that was also recorded at the Cow Shed studios with Gilad Atzmon [current Blockheads saxophonist, original member Davey Payne plays elsewhere on the soundtrack], that’s Gilad’s one appearance in the movie.

There’s a Rage Against the Machine-style Facebook campaign to try and get ‘Spasticus Autisticus’ to number one in March… (‘Spasticus Autisticus’ being Ian Dury’s 1981 composition for the Spastics Society, which was banned by the Beeb at the time of release, and, as if no time had passed, was recently cut out of a BBC 6 Music documentary about the Blockheads, to be aired this Saturday 16th, 22.00).

CJ: I heard about that, they’re trying to make it a hit. Well, great! Good on them, it just shows that there’s still a lot of conservatism in the media but they don’t have the same hold that they used to… it might happen, you never know.

I thought it was interesting when I heard the song was going to be cut; the song is about facing disability, really looking right at it, and by shoving it back under the carpet we prove we still can’t face it… I thought that was telling.

CJ: Right. There’s such a consciousness of being PC, there’s no room for any personal expression like that.

JT: I think it’s really good that they’re doing the campaign, I joined it last night. Thank goodness for the internet. It’s proven now you can’t keep talent down. It might not be the same as the Rage Against the Machine thing, but if nothing else it’s bringing real music to the youth again, it’ll make them go, "Ooh, this is better than X Factor", hoping for something good when there’s actually something good already there.

It’s a posthumous award for Ian but it’s also getting people to realise that the Blockheads are still out there and gigging [they never split up]. We’ve been through our transformations… All of us have grown up in a way.

Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll is out now on general release.

For more information on what the band are doing now visit theblockheads.com and for more videos visit the Blockheads youTube site.

More on the Blockheads latest album Staring Down The Barrel here and more about the Ian Dury & The Blockheads Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll – The Essential Collection on Demon here.