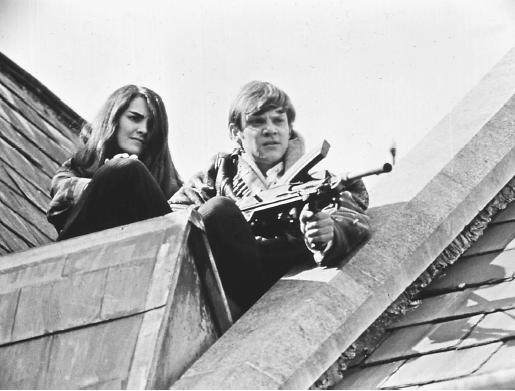

The final scene in Lindsay Anderson’s If…. is one of the most electrifying and incendiary in modern British cinema. Filmed in the spring of 1968, whilst students rioted in Paris and New York, the military assault of Mick Travis (Malcolm MacDowell) and his cohorts against their school masters seemed to chime perfectly with the mood of anomie and discontent amongst Britain’s youth, drawing queues round the block upon its initial release. This strange, (sur)realist film was derided as an "insult to the nation" by one of Britain’s ambassadors, and a certain Lord Brabourne, upon being shown an early draft, called it "the most evil and perverted script" he had ever read.

One cannot help but recall Jean Baudrillard’s line that, "Attacks on the reality principle itself constitute a graver offence than real-life violence." March into a real high school with an automatic weapon and blow your classmates to bits and it’s a tragedy; present the fantasy in a highly stylised fashion on screen and it’s an insult, perverse. Well, perverse it may be — but only in the precise sense employed by Jacques Lacan, in that a pervert will enact what a hysteric only dreams of. If….‘s principle writer, David Sherwin, remained somewhat equivocal about the denouement’s moral message, claiming that it showed Travis had become just as hateful as the whips and masters he so despised; but Anderson showed no such ambiguity, calling himself an anarchist and professing a desire to tear the British establishment down to its foundations. However, the inspiration for this final conflagration came from a French film directed some thirty-five years earlier — Jean Vigo’s Zero de Conduite.

Vigo, the son of Catalan anarchist militant Miguel Almareyda, was driven from an early age by both his father’s death (under "mysterious circumstances") in a French jail and the tuberculosis that would ultimaely bring about his untimely demise at the age of 29. During his short life he committed scarcely three hours to celluloid — a brief travelogue, A Propos de Nice; an even shorter ‘swimming lesson’ from French champion Jean Taris, Taris Roi De L’Eau; and two feature films, both masterpieces, Zero de Conduite and L’Atalante — prompting Lindsay Anderson to remark, "Few artists in the history of cinema have won reputation so high by achievement so modest. If, that is, works of genius can be described as modest."

Zero de Conduite, a film whose ferocity is matched by its hilarity and by its beauty (the children’s slow motion march through a storm of tattered pillow feathers is truly breath-taking) told the story, in typically lyrical fashion, of a conspiracy amongst boarding school children. It ends with the children occupying the school roof and pelting their teachers into submission with books and tin cans. During the writing process for If…., Lindsay Anderson and David Sherwin watched Zero de Conduite several times, inspired less by its anarchic spirit ("We had plenty of our own," claimed Anderson) than its poetic style, its mixing of fantasy and reality. In a letter to Jack Landman, written several years after If….‘s release, Anderson noted, "Of course, interestingly, If…. is very much more violent in its climax than "Zero de Conduite". And this although perhaps Vigo was nearer to being a professional anarchist than I have ever been."

‘Stand up, stand up for college,’ goes the school song, whose strains, accompanied by a sepia-tint wide shot of Anderson’s old almer mater, Cheltenham College, open the film If….. The melody was taken from ‘Stand up, Stand up for Jesus,’ a hymn that must have had a particular resonance for Anderson for, as a young critic in the 1950s, he used its titular demand as the title of one of his most famous essays for Sight and Sound: a call to arms to the critical establishment, demanding of his fellow scribes they ‘stand up’ for a more engaged, subjective form of film criticism, calling into question even the very possibility of critical detachment and objectivity.

Shortly after the end of the Second World War (he had joined up as a cryptographer in the last year of the war — and had been responsible for raising the red flag over the junior officers’ mess upon confirmation of the Labour Party’s election victory back home), Anderson had co-founded the film magazine, Sequence, with his friends Gavin Lambert and Karel Reisz (who he had met on a bus on the way to the National Film Theatre at Waterloo).

At the end of the 1940s, Lambert became editor of the British Film Institute’s house magazine, Sight and Sound, and Anderson and Reisz, along with Tony Richardson and Lorenza Mazzetti, became regular contributors, while also making their own short documentaries. In 1956, frustrated by the difficulty of getting their films seen, Andersoon, Reisz, Richardson and Mazzetti decided to join forces and put on a group programme at the NFT, featuring Anderson’s O Dreamland, Reisz and Richardson’s Momma Don’t Allow, and Mazzetti’s Together. In order to attract the attention of the press, it was decided to give the programme a name, and it was Anderson who dubbed it ‘Free Cinema’ and wrote the accompanying manifesto. The films, claimed Anderson, "have not been made according to any plan or programme: instinct came first, we discovered our common sympathies after. But all of us want to make films of today, whether the method be realist or poetic, narrative or montage. And we believe that ‘objectivity’ is no part of the documentary method, that, on the contrary the documentarist must formulate his attitude, express his values as firmly and forcefully as any artist."

O Dreamland was a curious, at times macabre, at times heart-warming, portrait of a Margate fun fair — a montage of attractions in a far more literal sense than Eisenstein had ever intended. Juxtaposing shots of a London Dungeon-esque chamber of horrors with the quasi-liturgical song of the bingo caller, the film made good on Anderson’s stated aim to "Look at Britain, with honesty and affection. To relish its eccentricities; attack its abuses; love its people." One of the film’s final shots is of a neon sign, promising: "The dreams I dream are yours to see over there in reality." Such would be Anderson’s pledge in the years to come.

During the course of the 60s, the original Free Cinema quartet would drift apart, with Reisz and Richardson finding international success and Anderson increasingly embittered by his own lack thereof. His first feature, This Sporting Life, was critically acclaimed but a commercial flop and it would be several years before he made another. David Sherwin and John Howlett, two school friends from Tonbridge College, were, in 1960, officially studying at Oxford; in fact they were spending their days at the cinema. "Seven films a day, over and over," claims Sherwin, "We were stuck. Total writer’s block. All scripts had been done. Then, I don’t know how, inspiration hit me like lightning; I stopped John, ‘Remember the words of William Wordsworth, ‘poetry is experience recollected in tranquility’ and the only experience we’ve got is our school, that Nazi camp, Tonbridge.’"

It would be six years before the script they came up with, entitled ‘Crusaders’, would reach Lindsay Anderson, and when it did, he immediately told Sherwin that it was "very bad." But the two soon found common ground with the decision that the script should move from reality to poetry, and that it should be ‘epic’. This word ‘epic’, cribbed from Brecht but given Anderson’s own personal spin, seemed to be bestowed with a number of different meanings, from the important and multi-layered, to the description of a structure based less around a developing narrative than the gradual exploration of a particular subject. In a letter to Sherwin from later that same year, Anderson would set out what he saw as the theme of the flim, "the image of a world: a strange sub-world, with its own particular laws, distortions, brutalities, loves."

Determined to film in his old school, Anderson went to the lengths of having Sherwin create a fake, watered down script to present to Cheltenham’s head master. A new title was sought, "something very old-fashioned, corny and patriotic. Like Kipling," Anderson suggested, and the producer’s secretary, Daphne Hunter, suggested ‘If’. Having loathed the poem at Oxford, Anderson immediately decided to stick with this new title, adding just a few dots at the end.

Despite the film’s anarchic, freewheeling feel, Anderson was utterly meticulous, demanding immense control and discipline from his actors. Everything was planned and scripted in advance — except for one scene. In the anteroom to the gym, immediately before being caned, the three boys are shown nervously waiting for their punishment, shot from a very high angle in one continuous take. Their words and actions are, in a sense, irrelevant. It is the camera that reveals the truth of the situation. For here, finally, the trio are reduced to what they are, children, mere nonentities. And only as nonentities, as the cut away to a multiplying amoeba suggests, are they able to become revolutionaries. As in the political philosophy of Jacques Ranciere, only once they have been reduced to naught, to the part of no part, are they able to assume the mantle of universality, and rise up on behalf of the all. The comic presence of knights and bishops amongst the attacked, the headmaster self-combusting in a puff of smoke, may suggest If….‘s ending is mere fantasy, a flight of the imagination; but it is a fantasy with potency, and explosive possibility. "One man can change the world with a bullet in the right place."

Lindsay Anderson’s If…. will be screened at Victoria School, Jersey, during the Branchage International Film Festival. For more information about the festival, visit the Branchage website