As someone who has seen a decent chunk of Robert Altman’s 39 films (including his HBO series Tanner ’88) it’s fair to say they can be a bit hit and miss. Along with all the moments of brilliance, memorable characters and effortless storytelling, there’s plenty of awkwardness, hammy acting and misfired ideas. But it’s always worth sitting through one of his films because while Robert Altman is not perfect, he is certainly never shit.

In fact, you could say that Altman was ground-breaking in his commitment to “not being shit”; an innovator in the field of “having integrity” and “not cow-towing to studio hacks”; a true maverick in his incendiary use of “restraint”. Altman is not the best director of all time, but for me he represents a kind of baseline we should demand, but rarely get, from films.

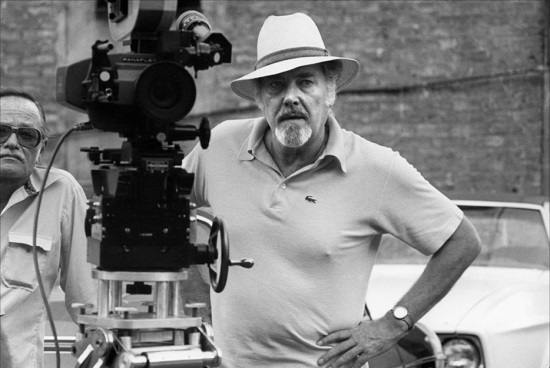

This is what occurred to me during a screening of a lovingly made new documentary, simply called Altman, which is in UK cinemas this week. The film itself is entertaining and well crafted, though there will be little to surprise long time fans, but it’s more valuable as a parable about the fickle film industry who routinely ignored Altman’s perfectly accessible and populist work. The documentary plays with the aphorism “Altman-esque”, which is bestowed on many films, but which is actually quite hard to define given his varied output. We are periodically confronted with famous talking heads answering the question “what is Altman-esque?” with responses like “not giving a shit”, and “showing vulnerability”.

I think Altman’s distinct contribution – his legacy – becomes a lot clearer if you think of this year’s best picture Oscar as a battle for Altman’s soul. Iñárritu’s Birdman and Linklater’s Boyhood are both daring, (somewhat) independent films with ensemble casts, which mix humour with drama and other Altman tropes; but if they were judged against Altman’s output, I think the wrong film won. [In case you were wondering there is an official battle for Robert Altman’s soul and that’s the ‘Altman’ award at the Indie Spirit Awards, which this year went to Inherent Vice, appropriately enough.]

Birdman, a story about a washed up movie star reviving his career through a troubled theatre production, is on the surface very Altman-esque but it is far too much the work of a self-aggrandising auteur touting his achievements. Altman’s style was always secondary to the story and the characters, perhaps because of his unconventional route into filmmaking. As the documentary describes, Altman started out making industrial and educational films as opposed to attending the naval-gazing film schools. Famously, one of his typical PSAs, warning against the dangers of “parties”, was seen by Alfred Hitchcock and Altman was given two slots on Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Altman became one of the most sought after television directors of the ’60s until he was fired from a job for daring to portray WWII in more shades than good and evil (drawing on his own experiences). He then tried his luck in feature films, in the last throws of studio system excess, but was again unceremoniously fired by Warner Brothers for having two people speaking at the same time: you know, like in real life.

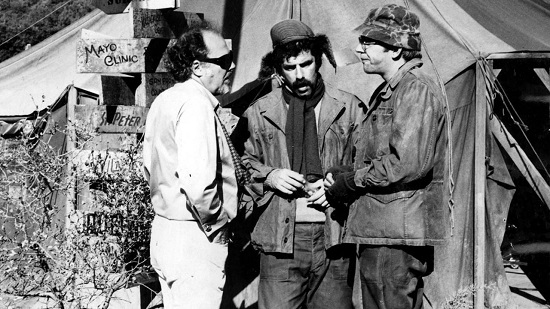

Luckily, Altman managed to come into his own just as cobwebbed conventions like these were being dismantled by the much younger film brat generation. But in contrast, Altman was not initially recognised for referencing Battleship Potempkin or the French New Wave but for his politics. MASH (1970) rode the crest of anti-Vietnam sentiment to take the Palme D’Or at Cannes that year and for the next 40 years, largely outside of Hollywood, Altman proceeded to make whatever sorts of films he wanted (westerns, crime dramas, wacky comedies, a live action version of Popeye). Rather than courting awards or popular recognition, Altman claimed in an interview that he was always doing the same thing and that thing occasionally locked step with Hollywood’s wildly fluctuating tastes – like a sine curve brushing past the baseline.

Iñárritu on the other hand has always seemed to be shooting for an Oscar. Even the choice of tapping Michael Keaton could be taken as a shrewd attempt to replicate Mickey Rourke’s Oscar-worthy revival in The Wrestler. But it is ironic that in Birdman, Keaton’s tortured actor is directing a stage version of Raymond Carver stories because it draws attention to just how un-Raymond Carver Birdman is. It’s strange to juxtapose the work of an author known for an economy of effort and muted, matter-of-fact stories with a bells and CGI whistles, high production values film, creaking under the weight of it’s own pretensions. Altman on the other hand was the perfect director to bring Carver to life with Short Cuts (1993). Altman intertwines several of Carver’s short stories in a way not unlike Iñárritu’s Amoros Perros and Babel but in Altman’s hands this becomes an understated device, highlighting the shared lives of LA dwellers rather than a calling card.

Birdman’s primary trick is the lack of cuts. It is a single take movie done the easy way with post-production stitching, as opposed to the hard way (Russian Ark 2002) or the clever way (Hitchcock’s Rope 1948) and adds little to the plot other than a bit of seasickness. When the same trick was used in Gaspar Noe’s Enter The Void, the floating camera conveyed simultaneously an out of body experience and one of those ghost train roller coaster rides – in other words it did thematic work, rather than just showing off.

Ironically, Altman’s other Cannes winning film The Player, about a despicable Hollywood hack played by Tim Robbins, starts with a 6 minute unbroken cut, but it doesn’t draw attention to itself except when one of the characters starts talking about the absence of long takes in Hollywood: that you couldn’t get away with the opening to Touch of Evil (which is also 6 minutes long) any more. Altman certainly used gimmicks and innovative techniques in his films: he developed a new way of recording each actor on separate audio channels so he could re-mix them – something which is standard practice today; Tanner ’88 mixed documentary and fiction – placing his fake presidential candidate alongside actual political figures like Jesse Jackson; but the gimmicks rarely announce themselves as such.

Richard Linklater, director of Boyhood, has also made a career out of gimmicks, but highly effective ones. Using animation in Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly conveyed the effects of drugs; Slacker’s chain of conversations simulates the meandering lifestyle of generation X Austin; Tape is appropriately enough in real-time. Similarly, Boyhood’s gimmick: filming a boy growing up over the course of 12 years is inextricable from the narrative.

Unlike the technically ostentatious Birdman, Boyhood is understated, flawed, occasionally trite, and yet so admirably committed to the purity of an idea, that it’s hard to fault. Too often these days stories and characters become corrupted by the craft of filmmaking. The Hollywood studio system on one hand treats film like it was cabinet making while the Avant Garde privileges films as mainly formal experiments. These are different sides of formalism which get taught at film school, and it’s these aspects of technique and style which sway with time and fashion and money. Yet it’s stories, characters and ideas which stay with us past awards season.

Robert Altman always preserved the integrity of the story and the ideas above all else: nurturing his actors and collaborators like a family and insulating them from outside influence. Perhaps this is why he could so easily work with television, film and even live theatre, because the particular medium was just a vehicle for some content. This is what I think of as Altman-esque – that baseline that we should expect from films – that you remember the content more than the form. The technique may be innovative and adept but always working invisibly, humbly in the background. Altman, is a timely reminder that not enough contemporary films deserve this modest accolade.

Altman is out in selected cinemas now