"The producers were used to producing porn." Catherine Deneuve

For a film that so brilliantly deals with the themes of pornography and its relationship to cinema and spectatorship, perhaps this should come as no surprise. For Repulsion, Roman Polanski’s first English-language film, is concerned with the seedy, dark, violent and erotic mode of looking that seeks to possess its subject: the beautiful female.

Using overexposure and stark chiaroscuro, playing with the peripheries of the image and extreme close-ups (the picture’s opening credits run across the eyeball of its beautiful protagonist) Repulsion reflects, with no small amount of irony, on how the visual language of cinema produces and reproduces a gendered spectatorship, much akin to Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960).

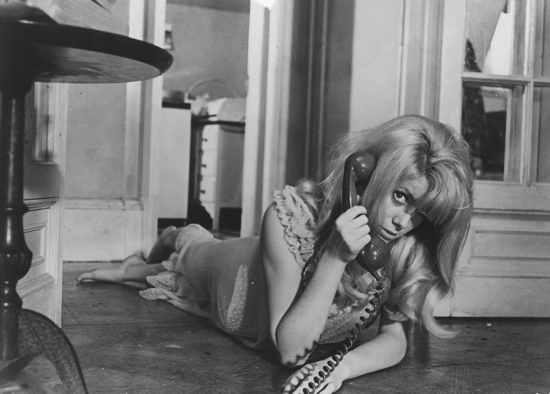

Carol (Catherine Deneuve) is a Belgian manicurist living in South Kensington. She walks to work each day, dazed and glassy-eyed and almost impossibly beautiful for her decrepit and boozy surroundings. Carol’s suitor, Colin (John Fraser) becomes increasingly frustrated by her dreamy indifference and fragile recoils, and, goaded by his friends, vows to declare his feelings for her. "I want to be with you all the time," he tells her, after forcing himself into her apartment, where Carol has barricaded herself among rotting rabbit carcasses and cracked walls, her mental state spiralling into paranoid obsession. In response to Colin’s declaration, Carol murders him with a candlestick. With each thump, the camera wobbles. We, the voyeuristic watchers – the men – assume the place of Colin’s battered head.

And so it is that Polanski aligns us – the spectators – with the predatory male gaze that so repulses and overwhelms Carol. In choosing this viewpoint for us, Polanski foregrounds the cinematic mechanisms at his disposal. "All right, Mr DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up," said Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) in Sunset Boulevard (1950), reminding us that the female visage, in all its soft-focussed beauty, was the founding motive for the close-up. It was a shot that structured much of cinema’s golden age. But in Repulsion, Polanski blatantly plays with this trope; the close-up of the beautiful Carol is only ever tantalisingly brief. For most of the movie, she’s filmed from low angles, feet up, or in the dark. Often, we see her reflected in a mirror or, at the beginning of her paranoid demise, reflected in a silver kettle that distorts and refracts her beauty. Similar to the famous scene in Apocalypse Now (1979), where Brando plays with the dim candlelight, refusing us a full glimpse of his gargantuan head as Colonel Kurtz, Deneuve and Polanski use light and dark to toy with our desire to possess a full, unadulterated image of Carol’s beauty. For the most part, visual possession is denied.

The writer and critic Masha Tupitsyn writes in her aphoristic book Laconia (made up of her tweets): "Horror is interesting because the body is being transgressed all the time – your body, someone else’s body. The monster’s body. In horror, the body ceases to be hermetic and is pierced, penetrated, pushed through, opened, dissolved; entered and exited in every way. Its social seal is ripped right off."

The transgressions she describes – physical, but also social, spatial and temporal – are central to Repulsion‘s sequence of events. As Carol’s worldview becomes increasingly skewed, she becomes obsessed by protecting herself against the transgression of her body by that of men: her sister’s married boyfriend Michael (Ian Hendry) frequently visits their apartment, staying the night and moving Carol’s sister to loud moans of pleasure throughout the night. His is a sonic, as well as a physical, invasion – "sexuality itself loudly proclaimed". His presence is synonymous with sex, which disturbs Carol. Earlier in the movie, she kisses Colin, but immediately retreats to her apartment to brush her teeth. In disgust, she realises she has used Michael’s brush. Thus, the men that so repulse her have twice invaded her mouth.

Appropriate social behaviour is soon lost on her too, the sacred and the profane dissolve. She goes to work with a rotting rabbit heart in her neat white handbag. Then, while manicuring a client’s nails – gouging the unwanted skin from above her nails – Carol cuts her. Blood, the stain on women’s imagined purity, disturbs the contained, feminized environment. All that is stereotypically feminine is turned upside down. Polanski, with acerbic wit, presents us with a demented, topsy-turvy femininity.

Charlie Chaplin’s films are even introduced as a joke on the subject/object confusion, which seems to be at the heart of Carol’s terror, as a beautiful woman in danger of being objectified and therefore possessed. Her friend describes the film she saw: "He was so hungry, he ate his shoes, and then pretended the laces were spaghetti! And there was this huge great big fat man, who wanted to eat him! He wanted to eat Charlie Chaplin! He thought Charlie was a chicken! And the chicken walked like Chaplin too."

Men as chickens to be eaten; shoelaces as spaghetti; women as objects to be devoured? Somehow, perhaps tangentially, it recalls Magritte’s The Treachery of Images (1928-29), and the painter’s comment that the pipe is not a pipe, but a representation of the pipe. Here, Polanski is perhaps suggesting something similar: the image of the woman is not the woman, yet there is still a displaced possession possible to us. A possession once removed.

Back in the stinking apartment, Carol’s paranoia becomes a kind of radical anti-domesticity. She breaks all the rules. She murders her spurned lover, and then serenely sits embroidering a virginal white nightgown. Among a long-forgotten rotting breakfast she irons some limp garment, the lead conspicuously not plugged in. In its subversion of the female ideal, Repulsion seems in some ways to be a precursor to films like Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), which riffed on the commodified versions of traditional women’s roles in modern society, or Chantal Ackerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), which slowed down female domesticated rituals so as to render them wholly bizarre and somewhat haunting.

Forty-eight years after its original release, Repulsion is still thrilling. Collapsing pleasure and pain, attraction and revulsion, fragility and volatility, it is a thoroughly compelling film about all the contradictions of cinema and its obsession with femininity.

Repulsion goes on limited theatrical release from today; a full list of screenings can be found here. Chinatown is also reissued nationwide, and both films enjoy extended runs at BFI Southbank as part of the venue’s Roman Polanski season.