A car sinking into a tar pit; a decomposed body slowly revolving on a chair; a human eye staring lifeless at the camera; a shower running. These are the sort of monochromatic images that spring to mind when you think of Alfred Hitchcock. Thanks to the UK’s most celebrated auteur, horror was re-envisioned – and some would say validated – by 1960’s Psycho. The arc of the film’s stab into popular American culture was a prosperous one, yet it was initially an enormous creative and financial risk. That the film got made in the first place is a miracle and a testament to the legacy The Master had built for himself. In the decades to come Stanley Kubrick was the only director who could prevent his film being shown, but Hitch was the only one who could force the studio to get his film made in the first place. So it feels only natural that, in Sacha Gervasi’s biopic Hitchcock, Psycho is re-envisioned as a framing device for a snapshot of his life.

In the wake of North by Northwest‘s commercial success, Hitch finds himself at a crossroads. The studios want something similar, he wants to do something challenging. He stumbles on Psycho – a shocking novel based on real events – which piques his creative interest, although this movie isn’t one Paramount want to make, lest their reputation as a film studio be damaged by a vulgar horror picture. But behind every great man, as they say, there is a great woman – in Hitch’s case Alma Reville, his wife and collaborator.

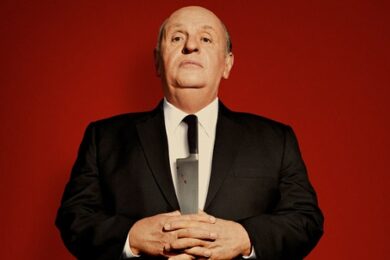

Reville is played with typical aptitude by Helen Mirren, and in turn Anthony Hopkins – walking on set straight from Madame Tussauds – provides a spot-on impersonation of Hitchcock. The great director’s protracted assonance and playful eyebrows are all brought to life with droll conviction, though not all of the man’s nuances are explored. The script by John J. McLaughlin, based on Stephen Rebello’s book Alfred Hitchcock And The Making of Psycho, focuses on the ‘iconic’ moments as opposed to any that convey the sense of there being a real man under the prosthetics. His infamous womanising is only hinted at, and is not allowed to distract from the most convincing aspect of the film: the romance between Hitch and Alma. While believable enough, their relationship does hinge rather too heavily on script-obligatory tête-à-têtes to bump their conflict-resolve dynamic along. Nonetheless, they do enjoy some genuine catharses, especially creative ones. Psycho’s denouement at its premiere is a pleasing thing to behold, especially given that we’ve been rooting for Hitchcock the entire journey – even if that’s mainly due to what we know about him already rather than due to the rounded-edges portrait Gervasi paints for us.

Hitchcock does dabble with some unconventional stylings – dream sequences in which Hitch is pulled along by breadcrumbs laid out for him by Ed Gein, the real-life killer upon whom Psycho was based, for example – but sadly these fall short, being mere vignettes that unsuccessfully fill in for any of the higher drives that were at play. As a result, the film is at its best when recreating scenes from Psycho. Gervasi possesses a deft hand for dealing with that film’s contents, but is considerably more cumbersome when he swings the camera round to show the lives behind the scenes. Alas, this is standard biopic fare which gleefully assimilates Hitch’s flair for the theatrical, but fails to produce any of its own.

Hitchcock is out in UK cinemas from today