The fragile male psyche has been explored at great length in modern American cinema. In the last three decades following the horrors of The Vietnam War, the male mind has been taken to the tipping point and all sorts of violent fantasy has spilled out onto celluloid. Taxi Driver‘s (1977) Travis Bickle, is perhaps the poster child (in a very literal sense) of the damaged post-Vietnam male. His descent into paranoia and isolation is an explicit account of a post-traumatic syndrome sufferer. Entombed within his taxi cab, Bickle’s journey is towards a internalized hell that lies within the hell he sees around him. In order to make his surroundings right, his only answer is violence and disobedience. He is an innocent child given the tools of male adulthood to combat the cruel and bullying world, and his only method is to lash out.

Bickle is only one of many males nudged to the point of no return. As is well documented, the Ronald Reagan era brought a cinematic machismo that complimented the administration’s male-centric internal and external policies. The era personified the barbarianism of Schwarzenegger, Stallone and Willis, and made expectable use of extreme force to bring into line rogue foreigners and perceived internal threats such as drugs, corruption and gangs. Films such as First Blood (1982), Commando (1985), and Die Hard (1988), show wise-cracking macho men all dishing out sweet vengeance of an explosive nature. It’s interesting to acknowledge that the above excessive reactions to the world are from a male perspective, and play instantly into the hands of a male dominated audience lapping up the fantasy of extreme retaliation. Male film directors have conjured up an image of the male mind slipping into psychosis and acting with brutal force in order to put their perceived world view back on track. Yet reality would deal these zealots a lawful and swift blow, putting their Action Man fantasies to rest. In fact, It has been the role of the female director to explore the real nuances of the male mind without descending into fantastical violence. In the two films discussed here, Kathryn Bigelow’s Point Break (1991) and Mary Harron’s American Psycho (2000), the fragile male mind is subject to insecurity, trivial rivalry, insanity, and certain humiliation, yet with a sense of compassion and understanding that is deeply lacking from the male perspective.

Kathryn Bigelow’s last two movies The Hurt Locker (2008) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012) have both glorified the masculine desire of fighting in hard-bitten wars. Both films, set within the confines of the Iraq War, could be seen as a much needed jingoistic push for support of the conflict from disillusioned Americans. However, Bigelow’s films have always showed a darker thread of the male desire to engage in violence for the rush of adrenaline it provides. In her high octane film Point Break, Bigelow focuses on the surfer community and its thrill seeking participants. Centering on the investigation by young rookie FBI agent Johnny Utah (Keanu Reaves) and his older partner Angelo Pappas (Gary Busey) on a bank robbing gang known as the Ex-Presidents, Utah goes undercover with the surfer community when Pappas proposes that the gang are seasoned surfers. Although young and courageous enough to learn the basics of surfing, Utah begins to descend further in the subculture, picking up the slang and the posture of a surf bum, developing a sexual relationship with his surf tutor Tyler Endicott (Lori Petty) and becoming friends with the charming and charismatic Bodhi (Patrick Swayze).

Bodhi and his crew of surf bums take Utah under their wing and discuss with him the spiritual aspects of surfing and extreme sports. At first Bodhi comes across as some sort of mystic guru, bestowing his knowledge and lifestyle on the young Utah: "you still haven’t figured out what riding waves is all about yet have you? It’s a state of mind, it’s the place where you lose yourself and find yourself." Everyone in his presence is in awe of his masculinity, yet also the sensitivity he displays. When he expresses his desire to ride the waves at what he predicts will be a great storm at Bells Beach, Australia he lets it be known that he is willing to sacrifice his life for the ultimate thrill: "If you want the ultimate, you’ve got to be willing to pay the ultimate price. It’s not tragic to die doing what you love."

When it is revealed that Bodhi and his pals are in fact the Ex-Presidents, it comes as no surprise to the narrative of the film. Yet Bodhi reveals aspects of his personality that were only hinted at before. His unquestioned need for control means that everyone who is within his orbit is suddenly at risk. When the gang discuss how to handle Utah, Bodhi exposes a detachment from the world that leaves him in the realm of fantasy: "This was never about the money, this was about us against the system. That system that kills the human spirit." The gang apprehend Utah and take him skydiving, here they reveal to Utah that his love interest Tyler is now in the hands of Rosie, a goon of Bodhi’s, who he has given orders to kill Tyler if the gang do not meet at a designated destination and time. They take Utah along for one last bank robbery, but Bodhi orders his gang to hit the vault, which displays a recklessness that puts them all in danger, and is also at odds with the level of control Bodhi demands. By the end of the film only Bodhi and his accomplice Rosie survive the getaway, the rest are killed. Bodhi seems virtually uncaring about the loss of his friends and drives away with Rosie and the money from the last robbery.

Bodhi’s thin veneer of spiritual calm and composure hides a deeply troubled and violent interior clinging to the edge of his own sanity. His philosophy of control through menace is frightening, and its only in the last moments of the film were the audience realise how disturbed Bodhi has become, or perhaps always was. He explains to Utah just prior to the last robbery that "Fear causes hesitation, and hesitation causes your worst fears to come true." It becomes clear that Bodhi is on a death trip and the film ends with him paddling out on his surfboard towards a ferocious sea. His speech about paying the ultimate price for doing what he loves could now be interpreted as a nihilistic sentiment, as opposed to a noble one. What also becomes apparent is that his initial friendship with Utah develops into a complicated rivalry. Bodhi has already mastered his control over his gang of surf buddies, but it’s clear he has something to prove to Utah, especially as Tyler was once his girlfriend. By exposing Utah to the dangers of night-time surfing, skydiving and other extreme elements of his character Bodhi is attempting to overpower Utah as the dominant male. When it becomes clear to Bodhi that Utah is an FBI agent, rather than do the smart thing and go on the run, he confronts Utah and begins a campaign against him, recruiting him against his will into a robbery without a disguise, kidnapping Tyler and using her as ransom for his escape.

Bodhi eventually provokes the fascination he seeks from Utah when after a death defying leap from an airplane leaves Utah injured and unable to apprehend his man, Bodhi boasts "I know Johnny. I know you want me so bad it’s like acid in your mouth. But, not this time." This leads to a yearlong, worldwide pursuit by Utah that eventually leads him to their confrontation at Bells Beach, in which Utah is still under Bodhi’s spell and eventually allows him go and ride the waves. As Bodhi rides out towards his certain death, Utah discards his FBI badge.

Unlike the free spirited Bodhi, American Psycho‘s Patrick Bateman has become the embodiment of late capitalism and consumer cultures drastic affect on the male persona. Like his 1980’s counterpart, the reptilian Gordon Gecko from Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987) Bateman is detached, unfeeling and uncaring towards the people around him. His only concern is himself and his outward appearance of wealth. His preoccupation with his external physique, grooming products and routine, expensive attire, appreciation for music, and his perceived social status, has left an internal void in which his delusions and fantasies begin to bleed into his reality.

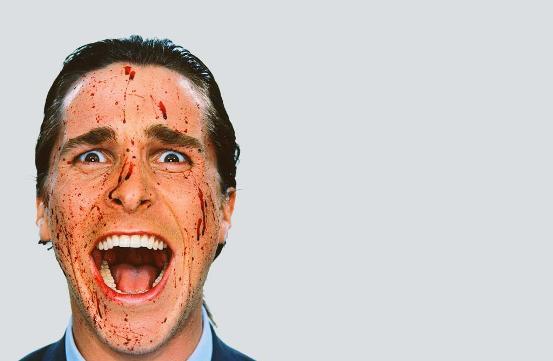

An adaptation of Brett Easton Ellis controversial novel, the Bateman of the book is far more sadistic than the film version explores. In Ellis’ novel Bateman indulges himself in drawn out acts of torture, rape, mutilation, cannibalism, and necrophilia, that are explained and dissected in graphic detail. The male interpretation (i.e.: the author Ellis) of Bateman’s behavior is to allow him to indulge in the most atrocious violent and sexual acts. The film version as adapted by Canadian film director Mary Harron (the director of I Shot Andy Warhol, the biopic of feminist activist, and author of The S.C.U.M Manifesto Valerie Solanas) focuses instead on the narcissism and vanity of Bateman and his male colleagues and leaves the acts of murderous violence and savagery to the imagination of the audience (apart from one scene in which Bateman attacks his nemesis Paul Allen with an axe).

By focusing on Bateman’s petty concerns, Harron provides an account of male insecurity and anxiety in a world of consumerism. One scene in particular exemplifies Bateman’s petty obsessions. Whilst waiting for a morning meeting to be called Bateman and his colleagues compare their new business cards. Bateman, seemingly delighted with his new ‘Bone’ coloured and ‘Silian Rail’ typeset card is then made delirious with jealousy over his colleagues far superior card: "Look at that subtle off-white coloring. The tasteful thickness of it. Oh my God; It even has a watermark." The scene demonstrates a man seething on the edge of sanity. However, with the majority of the violent acts left to the imagination of the audience it becomes far easier to understand that Bateman has perhaps imagined most of the atrocities he has committed. In a later scene Bateman pours a confession to his lawyer over the telephone: "I don’t want to leave anything out here — I guess I’ve killed maybe… 20 people… maybe 40! Uh- huh huh-I have uh… tapes of a lot of it. Some of the girls have seen the tapes — I even… I ate some of their brains and I tried to cook a little." Bateman’s continuous rant about his exploits displays obvious panic as he thinks his time is up, and the authorities are closing in, yet also uncertainty over how many acts of violence he believes he has committed. Without the audience witnessing the ordeals (unlike the book where every detail is explained) we have a sense that Bateman has simply lost his mind and is victim to his own vulgar delusions. In many ways Harron’s film deals with the damaged male psyche in a much more effective and humorous way than the source material.

It’s fitting that British actor Christian Bale would transfer Patrick Bateman’s rich, egotistical capitalist to the reboot of the Batman franchise. The spoilt rich boy Bruce Wayne’s excursion into hi-tech crime fighting as the sinister Batman (drop the ‘e’ from Bateman, coincidence?) also reeks of a delusional mind, one that is fighting other members of his gender who suffer from the same instabilities. What Bodhi and Bateman share is that their supposed wealth, good looks, knowledge, and importance within their social hierarchy, still leave them yearning for some form of violence and disorder to break the monotony of their lives. In Bodhi’s case his violent bank robberies are a justification for him and his comrades to be "against the system" and allow them to maintain their unstable spiritual journey, whilst completely detaching themselves from their vicious tendencies. However, Bodhi’s absence of reality will not be broken even when he is unmasked by FBI agent Utah and his gang are all killed. This reveals a lack of apathy from Bodhi.

Bateman seems generally disconnected from the murderous crimes he commits and instead his reality is fractured by moments when he feels his social standing or masculinity is in question (the business card scene is a classic example of this). He finally breaks down when he realizes that he might have been found out, but his mind is so warped by the violent imagery that he cannot connect his real crimes to the ones he has played out in his head. Either way both characters go unpunished for their crimes, real or otherwise. Bodhi is allowed to go free and head into a surf that will no doubt kill him, whilst Bateman’s manic confession is assumed to be a joke, thus leaving the audience interpretation of his crimes open to debate.

Bigelow and Harron’s interpretation of male criminality, is filtered through a lens of insecurity, jealousy, and a distorted view of reality. Although both these males are open to violent and destructive behavior, there is an internal war being raged that gives the characters depth that a male interpretation might choose to ignore and simply illustrate with excessive violence and stinging one-liners.

Follow Stephen Lee Naish on twitter at @steleenaish