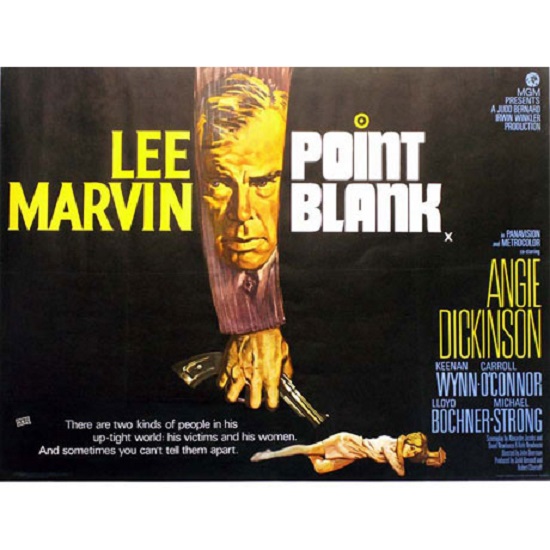

He is, of course, called Walker. No first name. Just Walker. And in the key early scene, we watch him, head-on – point-blank, very nearly – striding through a long corridor in which his footsteps echo long after the camera cuts away. He moves like an engine of relentless vengeance, which is what he is. Between them his name and his purpose evoke a more baleful manifestation of another Ghost Who Walks – The Phantom – and he is, it will be suggested repeatedly, a dead man. A retributive spectre.

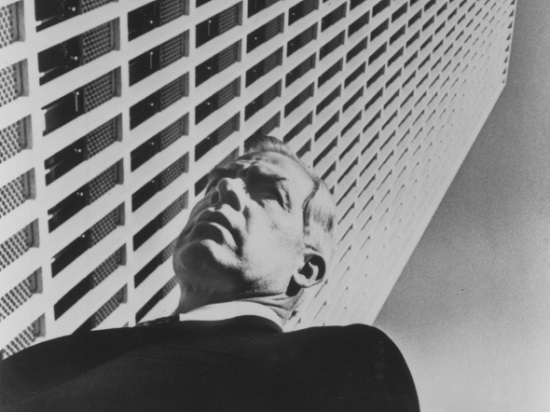

No actor could have better suited such a role than Lee Marvin, he of impassive, granite face and manner. None would, until Arnold Schwarzenegger was cast in The Terminator seventeen years later. Schwarzenegger played to perfection a machine which outwardly resembles a man; Marvin, a man who outwardly operates like a machine. But Walker remains a man, if an all but unreadable one, and Point Blank is as much a film about human recollection as it is about mechanical violence. It just so happens that there’s an awful lot of mechanical violence in it. Yet it remains unresolved whether, after the first five minutes, anything that happens in it has happened at all.

The film is spare, pitiless and at times laconic to the point of inadvertent comedy. One has to suspect it as a source of inspiration for the Naked Gun series. The book from which Point Blank was adapted is a Donald E Westlake (aka Richard Stark) pulp item, The Hunter, and the resulting screenplay is both ingenious and preposterous: ingenious in its structure, preposterous – at least, in patches – in its dialogue.

That dialogue is born of a marriage (an incestuous one, I suppose) between Film Noir and Nouvelle Vague, attempting to combine the terse melodrama of the former with the quizzical existentialism of the latter. Not all of it has dated well, although it does contain some wonderful moments. A hipster hitman, full of professional admiration, tells a crime boss whose syndicate our anti-hero has thwarted, "Walker’s beautiful [he doesn’t add, "Baby," but you sense it’s a close-run thing]. He’s just tearing you apart." That boss, Brewster, a chubby, exasperated, indignant little apparatchik, berates Walker: "You’re a very bad man, Walker, a very destructive man! […] You threaten a financial structure like this for $93,000? No, Walker, I don’t believe you. What do you really want?"

That being the sum Walker attaches to his mission; and that being the question that sits right at the heart of the film. But Brewster has Walker bang to rights, and for one moment, the only such moment in the film, this implacable Golem, a psychological tabula rasa upon which events have scrawled the word "revenge", is at a loss. "Somebody’s got to pay," he says, hesitant, confounded, and it’s more a plea than a threat. Because this is the ’60s, and the syndicate is, inevitably, "The Organisation". It’s one man against The Man, the embattled individual taking the fight to the corporation, and it is not yet the age of the story arc which says the individual must win.

It is the age (just begun, in Hollywood) of fractured narratives, of studio cash handed to film-makers bent on experiment, of that brief, glorious spiking of the mainstream with mind-expanding counter-culture. It’s here that the structure of the movie comes into play – although how much of this is down to the original script, and how much to the direction and editing, is an intriguing conjecture.

Point Blank, is among other things, an urban Western, and if it was not influenced by Sergio Leone’s magnificent, doolally horse operas, then it’s certainly one hell of a coincidence. Leone may not have invented the devices employed here by John Boorman, but he certainly popularised some of them. His film centres upon a mysterious, taciturn, self-contained avenger who acts with economical savagery (an archetype in whose creation Leone himself borrowed from Japan as much from John Ford and company), and who will recur in a quasi-supernatural form, much like Walker’s, when Leone’s avatar Clint Eastwood gets behind the camera for High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider.

The film’s cuts and flashbacks and its impressionistic, adventurous use of sound, create a dreamlike, near-psychedelic quality in which separate times, places or events appear to co-exist. Nicolas Roeg’s famous device in Don’t Look Now – intercutting a sex scene with the couple reclothing themselves – is prefigured in a sequence wherein Walker, presumably miles distant, moves with inexorable menace towards his treacherous wife, who goes about her numb quotidian routine as if preparing for his arrival. When they collide, she psychically divines and answers his questions before he can voice them – and becomes the first of many to tell him that he’s dead. Is that a metaphor, or is his own mind trying to make him understand it as a literal truth? Are we inside the expiring imagination of a man whose nature is almost pure violence?

Intrinsic to the feel of the thing is the look of the thing, the setting of the thing. Although bookended by the first movie scenes to be shot at the defunct Alcatraz prison, Point Blank is indelibly associated with a Los Angeles harsh and bright on the outside (an abundance of brutalist sun-dazzled concrete and glass), and dark and barbarous on the inside. Like location, like protagonist, is the obvious message. The film is to ’60s Los Angeles what Get Carter (a much nastier film, despite Point Blank‘s reputation for ruthlessness) is to the Tyneside of the early ’70s. (Or rather, to a selective, semi-fictive Los Angeles, because few of its exteriors – although several of its characters – are shot away from downtown.)

The Los Angelenos we see – adrift in Edward Hopperesque anomie at a diner, or rubbernecking at the horrors wrought by Walker – are hollow of expression, bored, disconnected, quite literally pictures of alienation. If a church were ever erected to the mythos of Los Angeles as a place of lost souls, or a purgatory for men and women who seem to lack them altogether, then the stained glass window depicting scenes from Point Blank would fit between those commemorating The Day Of The Locust and The Long Goodbye.

"People who hate Los Angeles," says Thom Andersen, in his illuminating 2003 cinematic essay on his hometown’s depiction in film, Los Angeles Plays Itself, "love Point Blank." Boorman, he continues, "managed to make the city look both bland and insidious." While most critics recall the outer shell Point Blank constructs for the city, for Andersen "the highlight of the film is the astonishing tableau of grotesque interior decoration schemes. It’s enough to make you believe the ’70s began in the mid-’60s." Which they did.

Point Blank invoked the ’60s’ imminent ’70s comedown – the descent from delirious altered state to state of self-seeking dysfunction – before the era had reached its apex. Point Blank is about the 60s, all right, but not the peace & luv hippie ’60s of cultural history orthodoxy. It’s about what lay beneath all along, the hard, malodorous sediment exposed when the multi-coloured froth had washed away. In other ’60s films, The Man was the identifiable enemy of all joy and freedom – and if by chance he missed you, the pawns in his game (as in Easy Rider) would not. In Point Blank, joy and freedom are never factors in the first place; and the only difference between The Man and any man is The Man has got his act together. Strike down one of his heads and more will rise, hydra-like.

It’s a bleak, misanthropic film set in a bleak, misanthropic world. Its spiritual kinship is less with other movies of its immediate time than with the paranoid post-Watergate conspiracy thrillers to come, but it has none of the low-key hyper-naturalism of The Conversation or The Parallax View. It is sharp, lurid, intense, all high style and low blows. That’s what fixes it in the collective memory like a painted spike driven in with a polychromatic sledgehammer.

Point Blank will be appearing in selected cinemas around the country, starting with a showing at the BFI Southbank tonight, 29th March.