As opposed to most ‘argument’ films, which are dominated by pedantic voice overs or weeping celebrity chefs, industrial farming documentary Our Daily Bread lets the stark images speak for themselves. Without commentary or dialogue, the camera dispassionately documents what it sees: the beautiful, the ugly and the surreal.

Our Daily Bread seemingly delivers on the well-worn vegetarian argument that “if you eat meat you should be OK watching a cow be killed” but extends this to all manner of modern food production. Even vegans aren’t safe. If you want to enjoy your gala apple, you won’t mind seeing it sprayed with chemicals and washed in what resembles an Olympic sized swimming pool. If you want to stock up on three for £3 Tesco battery chickens then you’ll be fine seeing a football-pitch-sized carpet of the poor sods being vacuumed up, one by one, by a Dr. Seuss-esque tube.

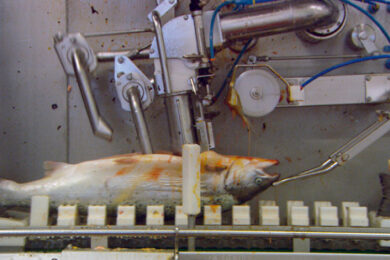

While most of the film consists of picturesque long shots of these otherworldly environments, it is punctuated with "primal scenes" of various creatures being slaughtered and processed. The gore isn’t that shocking, if you’ve ever watched a horror film, but the fact that it’s real makes it unsettling viewing: much like the real-life stabbing at the end of Gimme Shelter. The coldly efficient methods shouldn’t surprise us, unless you’re in a blissful state of denial, but the sheer scale of the barnyard holocaust boggles the mind. Also disturbing is the nonchalance with which the employees of these farms go about their grizzly business: an unassuming Eastern European woman slitting the throats of chickens on an assembly line like a trained killer; a joyless vet, up to his shoulder in the side of a cow, performing a caesarean. These scenes resemble one of those enormous Rube Goldberg factories at the end of Disney films with anthropomorphic critters jumping between conveyor belts – except that our protagonists don’t escape.

But watching this isn’t some tortuous act of hippy self-flagellation, because it’s so beautifully photographed and carefully structured. This is not an emotional endurance test like Enter the Void, it’s educational, entertaining, effortless to watch – even if occasionally through parted fingers. There will no doubt be academic debates about how aestheticising an abattoir might blunt the message, but it’s the films visual qualities that allow you to swallow this bitter pill. Like its wordless but more abstract predecessors Barraca and Body Song, Our Daily Bread begs to be seen on the big screen – to give scale to these vast environments.

It also filled with frequent darkly comic moments, including baby chicks being shot out of a conveyor belt like Nerf balls then mechanically sorted into some kind of filing cabinet. In one shot, what you presumed was the sky is later revealed to be an expansive greenhouse ceiling the size of an aeroplane hanger, while another zoom reveals about 10 such hangars with perfect comic timing. There’s also a rotating cast of baffling robots – one of which only serves to shake trees really hard.

But the film is never heavy handed with either the humour or the horror moments – it doesn’t need to be with this absurd subject matter! In a way it’s a striking example of how irrational ‘rational’ production can be. Some of the locations so closely resemble dystopian sci-fi or Saw style horror sets they’re almost trite. It seems that the engineers of these environments aren’t very imaginative: having made no attempt to make an abattoir floor look like anything other than a nightmarish Francis Bacon painting.

Interestingly, the film chooses to focus part of its attention to the workers who operate all this machinery. While there’s an easy irony to watching food workers eating their lunch, the more interesting purpose of these portraits is to show that the workers are caught up in the same machines: stripped of their individuality, and made to do blindingly repetitive tasks. We the city bound viewer might laugh at these endless hallways, bunkers and killing floors only to realize that they’re not unlike the offices, schools and prisons we’ve built for ourselves. If anything Our Daily Bread invites us to question the value placed on things which are scientific, efficient or ‘productive’.

But it doesn’t seem that the goal of the film is to make us eat some kind of organic gruel for the rest of our lives, there are no easy solutions to the problems we see here. We can’t simply return to old ways of farming: our modern society and general standard of living is made possible through these methods. We also can’t simply just look back to “nature” for help – nature is just as cruel and unfair, just less efficient.

In a way the film is not a call to arms, it simply asks that we be aware of how we get our food. With it’s soothing pace and magisterial shots, Our Daily Bread it’s like a non-judgemental, David Attenborough nature doc – but for the new nature we’ve constructed around us but always take for granted.