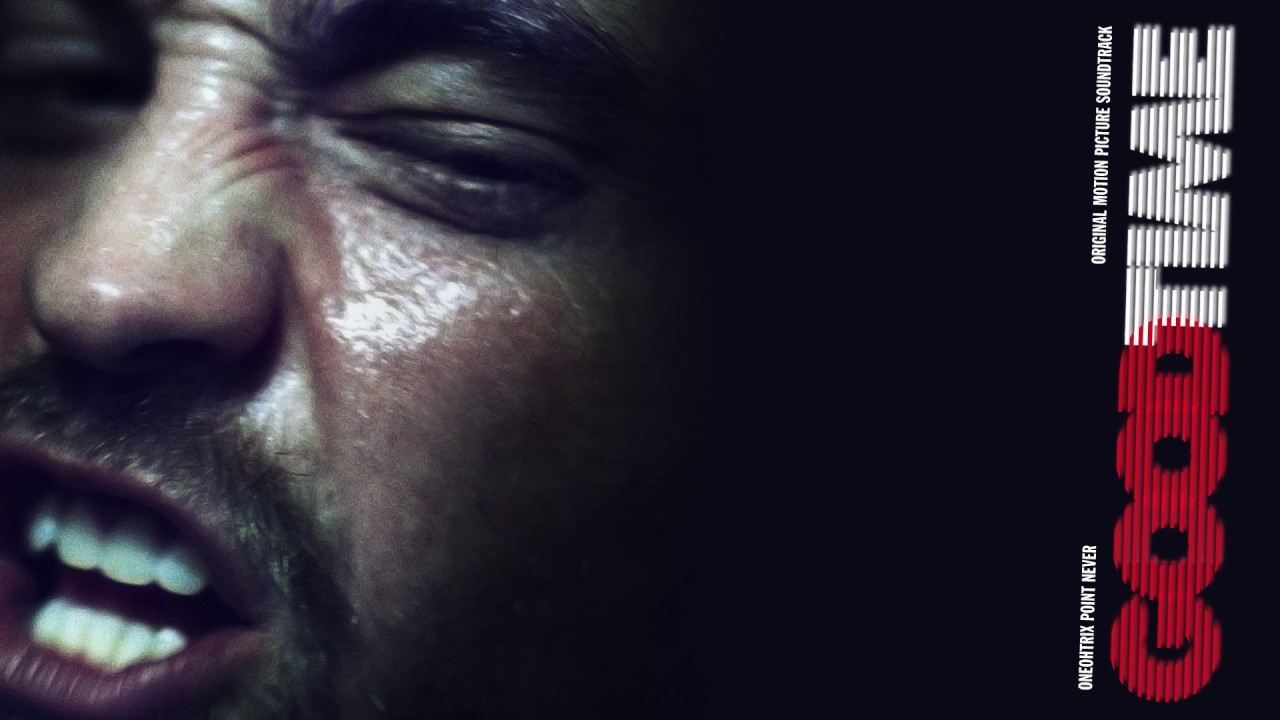

From the outset the music of Daniel Lopatin – AKA Oneohtrix point never – has been inextricably linked with visual media. From his early audio-visual project Memory Vague to his collaboration with Brian Reitzell on Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring and throughout various live soundtrack appointments, Lopatin’s questioning intelligence and desire to push his music to its furthest reaches is often most keenly felt through his approach to visual media. However it is only with his recently released soundtrack to Benny and Josh Safdie’s New York crime drama Good Time that lapotin has had the opportunity to create a score under the name Oneohtrix Point Never, and the release bears all the hallmarks of the music that has made his name. Pulsating, ominous, rich in skewed samples and sudden eruptions of squalling noise, Good Time is as much a Oneotrix album as it is a promotional item. This singular approach was recently rewarded when Lopatin won the soundtrack award for Good Time at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, the first major film industry award for an electronic score since Trent Reznor’s Oscar for The Social Network. The Quietus chatted to Daniel about his score, his approach to collaboration and how the whole proect came together.

I think this is probably the first significant reward for an electronic score since The Social Network. What do you think that is making the world of cinema respond to electronic scoring right now?

I can tell from having had a few other interviews, speaking to magazines like Cahier Du cinema, that it seems to be something that is still exciting for people that don’t really listen to electronic music on a regular basis. For me it’s like “Yeah, duh, of course it’s my life” But getting together with the Safdies and making a plan for the film meant hitting the books and seeing what’s happened prior. There’s already this rich history of electronic music in film. But it’s only recently you’ve had someone like Hans Zimmer coming out and explaining his process, talking about what he does, and him being able to say “Look it’s a blend of natural and synthesised sound that you are listening to”. I think people are starting to wrap their heads around a more nuanced understanding of what they hear when they go to the movies.

Electronic scoring tends to get associated with horror film and science fiction, are those the kind of things you enjoy?

Yeah, anybody that’s familiar with my work knows there’s a sort of tape-head, midnight movie aspect to my personality that comes out in what I do. You look at that period of time in general, it was a renaissance period for the synthesiser. They weren’t just these massive unplayable, academic laboratory machines. They started becoming a thing that John Carpenter could play a little tune on and throw in a film. So I think as it became democratised it opened up all of these options in the mid or lower tier budget film world because they need music and they need it fast and they don’t have any money to do it any other way, so you start hearing all of these incredible textures applied. But the thing is you can hear them everywhere. I always go back to Abigail Mead’s score to Full Metal Jacket, and a more subtle use of electronic texture that was happening in all kinds of films. Yes, horror, sci-fi that makes sense, it’s pretty logical to reach for a synthesiser to make that allegorical jump. But to me the real contrast is when you work against the cliché in some way and see what alchemical combinations come out of using things somewhat inappropriately.

How did you come to get involved with the project?

The Safdies were aware of me going back quite a while. I think there was a mix going around that had ‘Behind The Bank’ on it that they were listening to for a long time. So they had me over to their mid-town office and were like “Behind the Bank!” and I was pretty impressed that they liked that song. It’s an ideal thing when you meet artists that you feel a natural kinship with. I know that sounds clichéd but in fact it’s kind of not because most collaborations, for anyone that’s really gung-ho and has an idiosyncratic vision of what they want to do, are very hard for a lot of artists. But when I met these guys it was incredibly natural. We’re all obsessives about our respective mediums, in the sense that I had a million questions for them about film, and they had a million questions for me about music. We were like junkies with an unquenchable thirst to learn about each other’s techniques and understand each other’s opinions and points of view, so there was this never ending discourse that didn’t feel like work at all, it was just basically friendship. That made it very easy to obsess about the film. We were in my studio together working on it in tandem, which was also pretty new for me. I’m not totally comfortable with the idea of anybody standing over my shoulder and yet what I need from a film is to have an intimate understanding of it through a relationship with the creator. I realised that it was to the film’s advantage to have Josh come over to the studio, hang out with me and almost go frame by frame. Get him a familiar with my process to the point where could almost direct me.

How long did the process take?

Let’s put it this way, it took 50 more days than was allotted, so he was extremely upset on an administrative level, like “Hey you’ve got to wrap this up you’ve got things to do!” And I’m like “No I don’t have to wrap it up, we’re making a masterpiece!” You’re so deep in the cut that you’re like “Don’t fuck with me, this is significant work we’re making.”

You’ve worked with visuals a lot, and on a couple of films but this is the first soundtrack under the name Oneohtrix Point Never…

This is the first full Oneohtrix score which basically means I was given the keys to the Corvette. No body told me “Hey do this subtly.”

This film is harking back to a time in cinema, specifically American independent cinema that really privileged naturalism in dialogue and also privileged the camera as as this voyeuristic entity able to frame things in a filmic language and make you think that you yourself are the camera. I think it’s the beginning of a different kind of formalism in cinema. If you look at a lot of New York crime cinema you can see a kind of aspirational film making that’s trying to address the history of the genre and also break away from it completely. So when I sat down with the Safdies and said “OK clearly we’re working within genre here, clearly we have to think about the precedent for stuff. We have to think about Abel Ferrara and William Friedkin and what really thrills you. What are the dynamics of all the clichés? How do you get someone’s pulse pounding actually?” I know the critics will say “This was a pulse pounding film”, but what’s the latent formal thing that’s happening that feels like that? I had to figure that out, and it was educational. I had never really considered how to get from point A to point B over and over again. That’s the dynamic at work in any action or thriller movie. It’s a constant vacillation between relief and stress.

So it’s a lesson in cinematic deconstruction from your point of view as well?

Yes, because from the get we were saying “we’re making a genre film, we’re going to break certain rules and do things our way but what are we working with here?” I had never done that before.

It’s a powerful album in it’s own right. Was there ever any worry about the intensity of the music overpowering the visuals?

They didn’t want it to be a compromise artistically. They were interested in Oneohtrix Point Never, they weren’t interested in hiring me for a job. I was psyched to give them a Oneohtrix score because it was something that I’d never done before, but then I pushed them even further and said “OK you’re going to give me total freedom to put out the soundtrack that I want.” Frankly a lot of soundtracks are functional, they’re hard to listen to because they’re basically ripping the score out of the context an asking you to listen to it independently on it’s own merits, and I wanted to change some of the pieces around. A lot of the timings to the pieces were so tethered to the action that they were to bizarre to listen to that way on record. I was so intoxicated about the idea of putting this record on Warp that I actually put in the time to make it listenable. I spent this whole other chunk of time reimagining the score as a record that you want to listen to. And if someone thinks it isn’t I will fucking fight them!

I heard a lot of different influences when I listened through the album. The one I was perhaps surprised by was the Daft Punk soundtrack to Tron.

Probably subliminally. I have a Daft Punk fetish. It’s a teenage love affair that’s outlasted all my other real time love affairs with musicians. Guy from Daft Punk actually contacted us because he wanted to hear the score. He had enjoyed the film, so I got a chance to talk to him about it which was incredible. I was shitting bricks.

How did Iggy Pop come to be involved?

Originally we were working with a ballad by Lewis, you know Lewis? I love the song ‘Like to see you again’. I thought that would work as something we could use at the end. I actually wrote some music around it and then eventually when it was time to actually find Lewis and ask him if he wanted to be involved we realised very quickly that, no, he doesn’t. He won’t have anything to do with anybody. So we were like “what should we do?” And my manager said, “Whatever you do just think big.” I was like “What would make me cry?” and Iggy came up right away. And luckily for us he liked it and we went from there.

Iggy was like the voice of God in the studio, He was coming in over the speakers over an ISDN connection. He was in Miami, we were in New York. So literally you’re sitting there looking at the clock ticking until you hear “Hey, who’s there?” He sounded like an angry old guy on his porch with a shotgun trying to figure out who’s on his lawn. He came into it with a bunch of different ideas, and understood the film inside and out. We had a great session.

Oneohtrix Point Never’s Good Time is out now on Warp