In his last major film, Orson Welles mused on the inevitable death of all artists, “Our songs will all be silenced, but what of it? Go on singing.” Timely as this was in the autumn years of a stubbornly still directing Welles, it’s far from the sagest of advice. A forty-four year downward spiral followed Citizen Kane, which could well have been bypassed more nobly had Welles’ signed straight in to the 27 club after The Magnificent Ambersons. Although littered with occasional flashes of former genius, fluctuating weight problems and diminishing sanity dogged Welles’ post-Kane career. The man ultimately became a novelty and, worse yet, a bad director. Yet he’s come to represent modern cinema itself. Once exceptional, his diminuendo is now the very archetype of any major directorial career that’s made it into 2013. Rest on your laurels and shamelessly keep filming until the grave. Though long since a lost cause, the latter-day Welles could have perhaps been reminded that it is always an option simply not to make a movie.

Western cinema is firmly in the low point of a fresh talent drought. Stuck in an ouroboros loop and drained of the promise that once permeated the format, it is visibly succumbing to the tedium of remakes, sequels and reboots. Post-modern self-obsession and veneration for the past has devalued any new directorial talent. The baby boomers have been holding the industry hostage since the late 1960s, and much like them it’s all starting to get a little bit old.

We see it to a similar but lesser degree in music. The likes of Dylan, Springsteen and McCartney unleash their umpteenth album or go on yet another decrepit world tour, seemingly addicted to the whole circus and unable to reflect on the putrid facsimiles their work has become. (Dylan’s unfortunately Never Ending Tour in particular smacks of a man almost terrified to go home and face reality). Each new album is welcomed as a triumphant “return to form”, sells x million copies, and is promptly forgotten as quickly as it appeared – unlike the artists themselves mind, so safe and secure are their vintage legacies. Woody Allen is cinema’s most obvious case in point. Prolific in volume (but certainly not quality), not since 1981 has the world had a full year free from Allen’s directorial efforts. Critical response has waxed and waned with time, but he’s simply never stopped, and it goes without saying that the world would have remained largely unchanged had Stardust Memories been his swan song. Midnight in Paris was almost omnipresent back in 2011, topping critics’ lists and giving the Pizza Express gentry something to appraise in between courses. The cinema-going public are no longer simply happy with the most moronic blockbuster available. We also expect a headier, more gourmet option to be provided, and in an industry as inherently opposed to risk-taking as cinema is, this more often than not means merely recalling former successes and calling in the experts.

It must be understood that the deadened quality of cinema is not symptomatic of a current generation that’s lacking. The fact that dated filmmakers and their decaying cinematic talent receive a biased hearing is essentially a systemic problem. Nostalgia-driven high culture and the dominance of film student critics weaned on conservative cultural theory have driven us towards a kind of mass myopia, unable as we are to disassociate filmmakers from their own past, or indeed a film from its maker. The prevalence of films about films is testament to this. 2012 saw Hitchcock, while this year we can already start feeling excited about Saving Mr. Banks – a film detailing the making of Disney’s Mary Poppins. What is the aim of this on screen history of cinema? Are we simply meant to sit in awe of how magical it once was and ostensibly never shall be again?

Scorsese’s Hugo may well have been innocuous but it certainly wouldn’t have been made, let alone given a second look in any other director’s hands. Indeed this film was itself a pointless 101 in Méliès’ films, oddly concerned with reviving the past and living through the medium’s naively revered advent. It was a winning combination before it was completed – ‘Scorsese’ plus ‘Sir Ben Kingsley’ plus ‘3D’ equals profitable hit. Entertainment compiled by market analysts – much like the worrying initiation of Netflix’s own productions. The sorry beginnings of Netflix’s House of Cards is indeed representative of the approach that is allowing the dinosaurs of Hollywood to thrive and proliferate well past their sell by dates. Netflix’s “Chief Content Officer” described House of Cards as a “perfect storm of material and talent” – albeit only once he’d simulated the stats using Netflix’s algorithm. ‘Political thriller’ plus ‘Kevin Spacey’ plus ‘David Fincher’ equals a hit. The series is even a remake (of our own British House of Cards lest we forget). A “perfect storm” of marketable pieces? Is that what entertainment and cinema can be boiled down to? What kind of hope does that give to new filmmakers, yet to carve their niche?

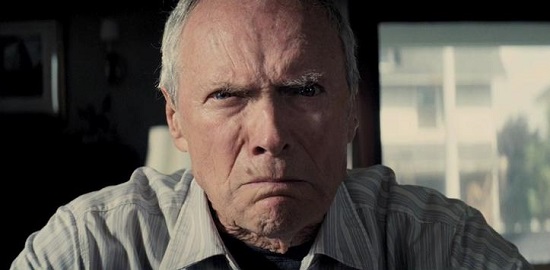

The cinematic crimes committed in the name of marketability are going out of control. Clint Eastwood for example has garnered endless positive feedback for his increasingly trite and almost painfully bland dramas. Films like Gran Torino or Invictus were received as solid movies – “Hollywood at its best” – when the truth of the matter is that these were more than just bad, they were boring. While the sure-fire combination of Nelson Mandela, Clint Eastwood and Matt Damon may well have assured its audience and made Invictus’ millions, these aren’t in fact great movies and neither are they harmless. When Clint started duetting with Jamie Cullum over the credits of Gran Torino, it boggled the mind that nobody stopped to insist this not go ahead. Film directors become trapped in the cult of personality like few other artists, their input into their work often blown far out of proportion and their creative carte blanche quickly becoming questionable. After all, major films require a team of thousands. The aforementioned systemic problem is one that permeates modern western society at large – it’s a generational imbalance, the result of an ageing population, and in this case, an industry that increasingly resembles an impenetrable fraternity.

The refusal to pull the plug on these lengthy careers is more than just stubborn, it’s downright selfish, even verging on malevolent. As if each multi-million dollar picture is going to be that missing piece from their canon. The best new filmmakers are largely resigned to the world of documentaries, creating almost uniformly intriguing films on relative shoestring budgets. Bart Layton (The Imposter), David Gelb (Jiro Dreams of Sushi), or Malik Bendjelloul (Searching for Sugar Man) prove the ingenuity and initiative of a new kind of young director, mercilessly filming despite being conscripted to a niche due to a mass perpetuation of a ruling class of Hollywood dinosaurs. We’re clearly not in deficit of great movies, but the upper echelons of cinema simply don’t know when to quit, understandably when one considers the yes men that populate major criticism. It’s okay not to make a movie, even if it’s what you’re known for, and although the last lot are soon to be extinct, stoking cinema with cults of personality is something to be abhorred, and that will surely persist unless addressed. We don’t need ancient heroic directors; we need to embrace new and original ones.