Northern Soul is a tale of two young lads (played by Eliot James Langridge and Josh Whitehouse) discovering the music that changes their lives. They harbour ambitions of DJing as a partnership and flying to America to dig out rare soul records. However, along the way their friendship is tested with tragedies, drugs and egos.

Set in the fictional northern town of Burnsworth in 1974, director Elaine Constantine was conscious that she didn’t want to “stitch any towns up for saying this is Oldham or Rochdale, it didn’t feel right calling them shitholes.” Northern Soul was shot in Burnley, Bury and Bolton (“all the B’s”) with the Wigan Casino dance scenes filmed at the King George’s Hall in Blackburn.

Authenticity is an overriding theme that crops up time and again with Elaine, and she didn’t skimp when it came to detail with everything from 70’s fashion and dance steps to sourcing out houses suitable for shooting.

Lisa Stansfield, who plays the mum of the lead character John Clark, also speaks to the Quietus. She describes the film itself as being “so true to form… it’s serious shit alright” and of Constantine being “a fucking anorak.”

Was there an overwhelming sense that this was a film that simply had to be made?

Elaine: Totally. Northern Soul was always going on in the background for me. I decided that I wanted to do some documentary footage on the scene. This was back in the early 90’s and because I’d been into Northern Soul since the 70’s, I kept filming stuff thinking it didn’t have the vibrancy or urgency that it had when we were teenagers, so I needed to re-create this to get that message across. Because all I wanted to do was say Northern Soul was brilliant. And the energy and ethos behind it, the need to get across the Atlantic to find music that was lost and the idea of bringing it back to people who’d never heard it before, with that absolute raw energy and enthusiasm that’s so esoteric was such a strong feeling. The only way I could portray that was to do it in fiction.

I’m not a writer and I don’t consider myself one. But the only way I could get that idea across was to write the script myself. I considered hiring writers but in the end none of them came through. So I ditched the documentary idea and went into the choppy waters of screen writing!

Lisa, how did Elaine approach you to feature in the film?

Lisa: When Elaine and I went out for lunch one day before she started shooting, she said that she really wanted me to play the mum! I thought, “that’s a bit different but alright I’ll do it.” Elaine had plans for this film being like a British Saturday Night Fever. When you’re a kid and go right back to how you remember the north back then that’s exactly what it is. It’s incredible how Elaine’s done it.

Could you relate well to John Clark’s mum?

Lisa: I think you’ve got to relate to every role you play. If you play a complete bastard after seeing the good side of them, then you’d see that no one is a complete and utter horror. I really did see part of the typical northern mum in me. She’s always on your case all the time and shouting at you, ‘take your sandwiches and don’t forget your coat’. But she’d always be there for you when you were sad. They weren’t bad northern mums. They were just looking out for you all the time.

How necessary was it to have elements of tragedy in the film?

Elaine: When I was young there were some fatalities with kids that would go crazy and would go over the edge on a lot of things and there were some tragic moments. I’ve been to some funerals on this scene and I’ve experienced that. This film is not Billy Elliott or The Commitments; it’s a real film about real things that really happened, warts an’ all. So it’s not been certificated to suit everyone. It’s a film that is truthful about the experience of growing up in the north in the 70’s. “

You ran a series of dance clubs in preparation for the dance scenes. How long did you run these for and how receptive were the kids?

Elaine: We started putting on these dance clubs for five years before filming. We’d started training the lead, Eliot James Langridge, six years before. We tried to do as many videos as we could to put onto YouTube to spread the word and get more kids through the doors. In all we had 500 kids.

We’d been filming these dance clubs for the kids that we’d been training up to populate the scenes. So many gatekeepers of that scene were like ‘No you’re not doing that, don’t do it!’ But then as soon as we started posting up these videos of the dancers, everyone suddenly came on board.

These kids were not dancers. This wasn’t Pineapple Studios with legwarmers and leotards, these were real kids coming in and going ‘I want part of that.’ They came for years and got involved with the culture. It wasn’t about ‘let’s work out how to do that move’. It wasn’t like there were mirrors in front of them and they were line dancing. It was more, ‘whack it on and get on the floor.’ Every so often we’d stop the music and say ‘Right, what kind of hand gestures are you doing? See what other people are doing and try to interpret what dance moves they’re doing. Fall in love with the music and we’re going to believe you when you’re on screen dancing because you’re really going through those emotions.’

Why are you so passionate about northern soul music?

Elaine: I think for me fundamentally it is because it’s got a melancholy sort of feel to it, mixed with euphoria, which is a very strange contradiction and it makes my emotions just lurch. So, there’s that element of it which gets you right there.

I’m talking about a particular number of records here. I’m not talking about Wigan’s Ovation or Tony Blackburn’s record or a load of shit they played in Wigan in the mid to late 70’s. I’m talking about the black, full-on late-60’s, heartfelt, raw emotional voices. And I think at the end of the day, I believe those voices when they say ‘My heart’s breaking.’ I don’t believe the voices that sing repetitive rubbish lyrics that are in the charts because there’s no feeling to them. And then I think that the accompanying music is so well matched to those voices that it’s almost like perfection.

Then there’s the etiquette around the scene and the kind of bonding with people that are into northern soul that appreciate that stuff that says to me, ‘we know something and we’re doing something that’s really special.’ And then there’s this wonderful dance floor etiquette, which is all about appreciating that record and dancing to it without any distractions. So you can just dance, get right under that track and be a part of it.

Because if you’ve experienced that music on the scene, especially as a youngster growing up, forming your opinions and the way you feel about the world, then there’s nothing quite like it. Every time I hear certain records and it doesn’t matter how many times I hear it, the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end. And that’s why it won’t die because it has that ability and effect to make that happen to me after 35 years or more of listening to it.

And then there’s another element to it, which is the progressive side. You’ve got a certain amount of DJ’s, collectors and promoters who are pushing that genre and boundaries. So you can still go out to nights around the UK and you can hear a record you’ve never heard before because somebody has had that kind of drive or passion to go to America or go through the internet daily for hours and hours to search out these masterpieces, bring them back and play them on this wonderful scene.

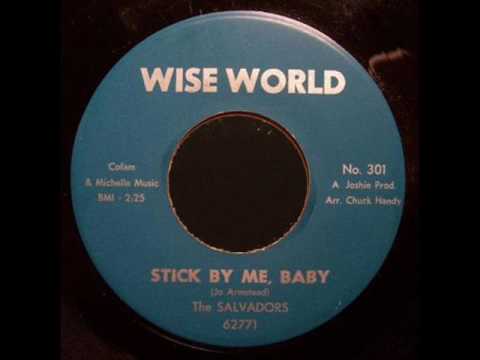

‘Stick By Me Baby’ by The Salvadors plays a pivotal role. Why that particular record?

Elaine: Because it’s brilliant! There’s something about that record that doesn’t immediately hit you when you hear it. It took me 2 or 3 plays but when you do get it, the song goes somewhere deeper than all the rest of them as there’s a certain kind of tension. It was written and produced by a woman called Josephine Armstead who then went on to be a boxing promoter!

Do you feel there could be a revival in the soul scenes popularity because of the film?

Elaine: There are a lot of those young kids who we got involved in the dance clubs who are now filtered into the northern soul scene. The age range is quite a wide spread. I think for it to be like how it is in the film, there would have to be a revival, like the one that happened during Quadrophenia. Because bands like The Jam emerged at the same time as the Ska revival in 1979.

That’s how I filtered into that scene as well. Remember I’m too young to have gone to Wigan even though I discovered northern soul in the 70’s through youth clubs when I was 18/19. I was in a mod/suede/skinhead type of network. That group of people is now everywhere and they’re the people who will go and see this film because though they may not be into northern soul they will be interested. Maybe there’ll be a revival and maybe those kids will have their own dos because they’re discovering that music for the first time.

If they take the doctrines of the Northern Soul scene, they’ll know they can’t DJ with anything other than the original vinyl. Be nice to think that music might be championed by the youth and that they stop listening to the charts, stuff that’s pushed into them and think ‘actually this is quality, I want a piece of this.’

Lisa, you released ‘Carry On’ as a single from your latest album, which is clearly influenced by northern soul. Have you written songs that have been influenced by NS directly or indirectly?

Lisa: I’m not sure really. I think that because I was doing the movie, it comes to the forefront of your brain and you can’t help but feel it. I’m terrible in that if I listen to a certain type of music or an album. I try not to when I’m writing because it influences me so much. Sometimes I can listen back to something I’ve written and think ‘Oh shit I’ve written someone else’s song!’ That’s why it’s so good! So you can’t afford to do that sometimes but I guess I’ve been influenced by so much soul music whether its funk, northern soul or Motown.

Fran Franklin a choreographer on the production team passed away a few months ago. What impact did she have in terms of the film production overall?

Elaine: The film was complete when Fran died and she saw the film in its finished form in February this year. So in that way it didn’t effect the dance sessions as we stopped doing them after filming. As for the dance community, they were completely devastated as was every member of the team; Fran was one of a tight bunch of friends who had been working towards this film five years before it was green lit.

Fran also was involved in the wardrobe of the film as her day job was as a seamstress so she made lots of skirts for the girls and lots of the jewelry too.

The film was dedicated to her memory and she lives on through her influence not just in dancing but her warmth and generosity.