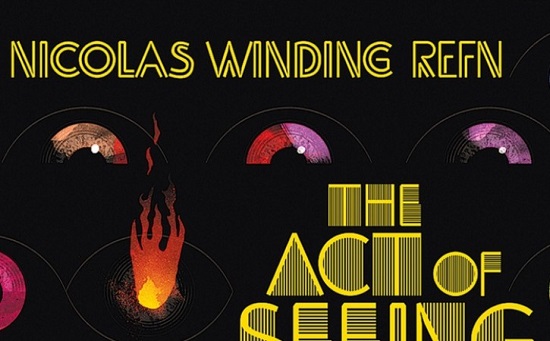

When director Nicolas Winding Refn purchased a massive collection of film posters from the writer Jimmy McDonough a few years ago, his initial reaction to them was disappointment. As he says in the introduction to his new book, The Act Of Seeing, a beautifully put together collection displaying the posters in all their glory:

“When I started to go through the pile, my first reaction was, why have I paid a sizeable sum for so much waste paper!… There were only a handful of titles I recognised.”

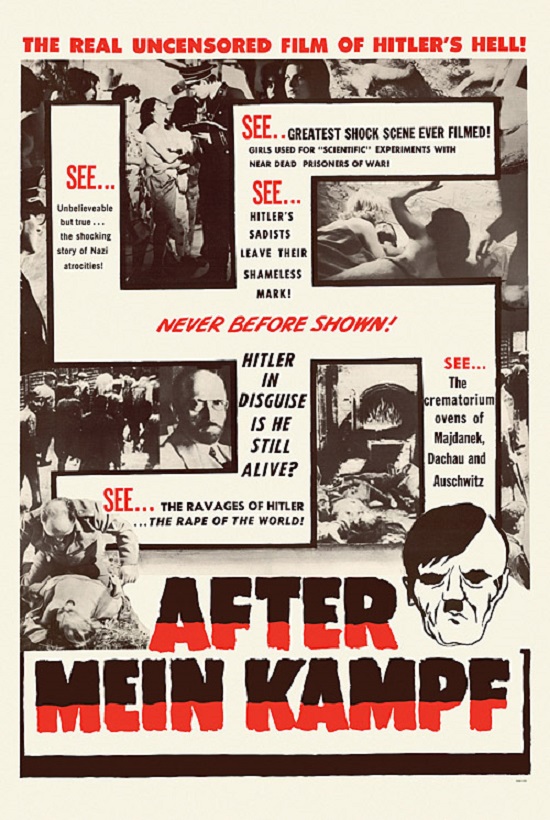

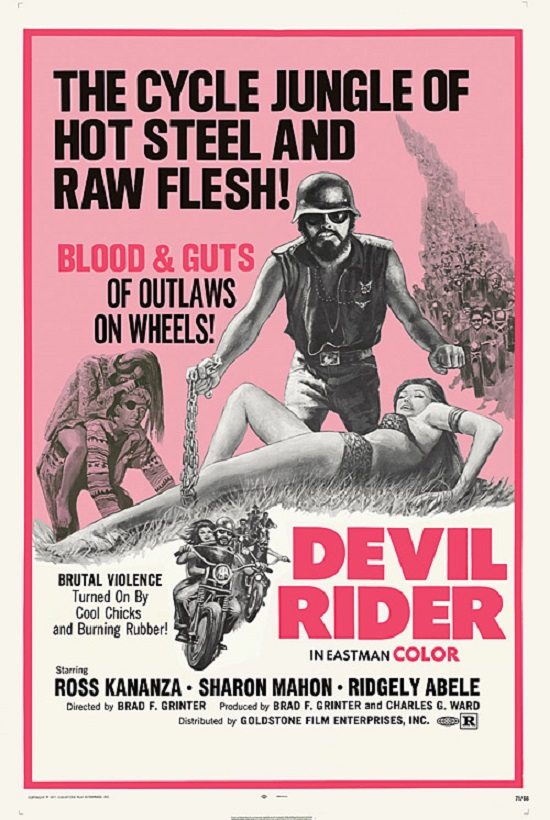

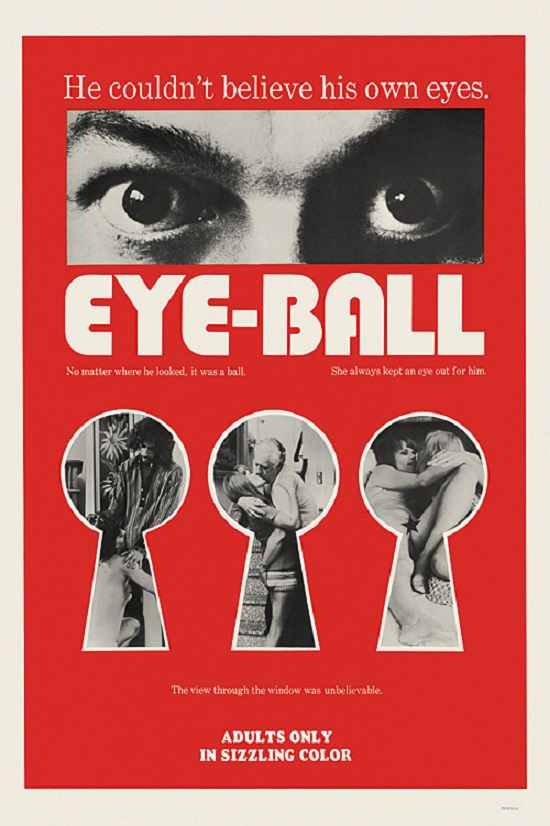

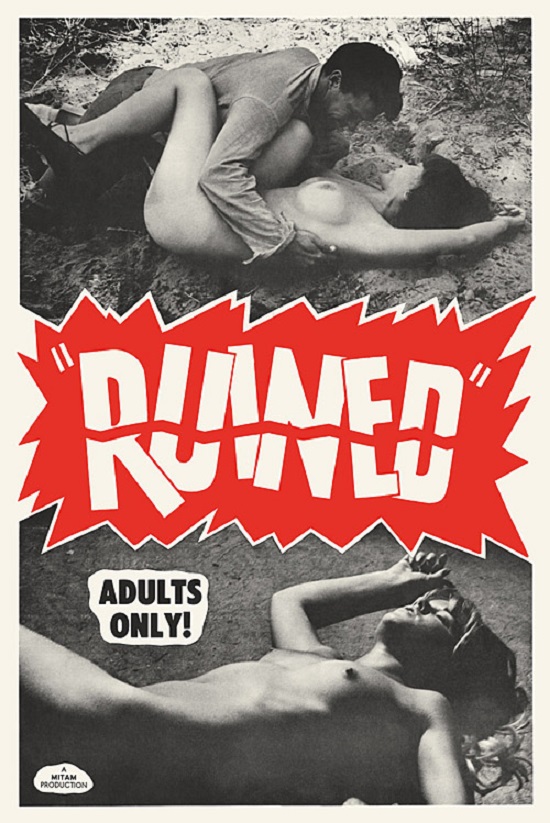

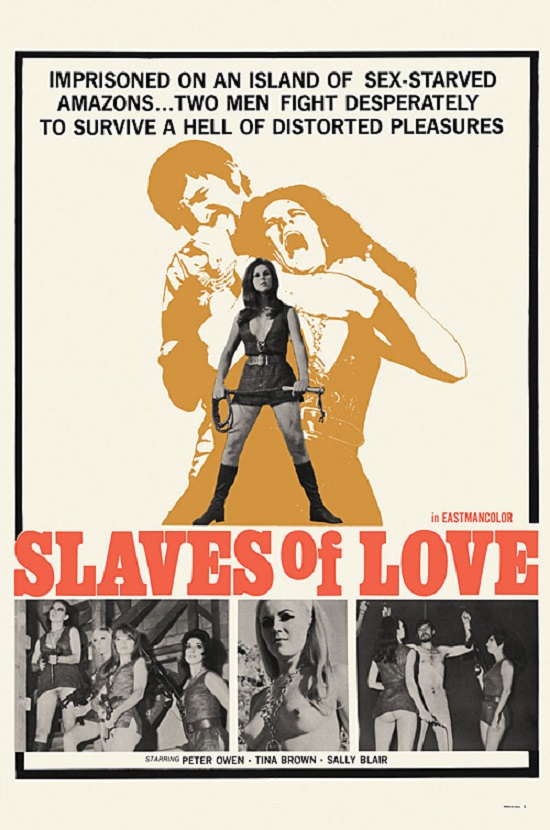

However, after a dinner with fellow film fanatic and journalist Alan Jones, a plan was made to collate these works of art together into a book that would idiosyncratically document a particular time and place in American cinema: the great era of fleapit Times Square picture houses and the equally grubby and notorious exploitation films that you could find in them. Titles like The Joys Of Jezebel, Spiked Heels And Black Nylons, Valley Of The Nymphs and (a personal favourite) Come Ride The Wild Pink Horse. The book is out now and is a glorious trip through a near forgotten but fondly remembered period of American film. To mark its release, The Quietus met up with Refn in London and talked posters, music, the subconscious and more.

I read in your introduction that there are a bunch of films in the book that you haven’t seen yet?

Nicolas Winding Refn: A lot of them. I’ve only seen about 15 titles.

Have you sought out any in the interim?

You can’t. Most of the ones I found interesting are impossible to get hold of.

You do wonder with exploitation cinema whether the poster is going to be better than the film, though.

Well, we all know that it’s all about the illusion of success.

Are film posters an aide mémoire for you? Do they sum up a lot of the experience of going to the cinema and seeing films?

Yeah, I’ve always enjoyed cinema posters as an art form and purely from a marketing perspective. But also cinema posters are a way that we define how we like culture. Cinema is a big machinery of entertainment so it’s something very accessible. A lot of art represents who we are. We use art to express our identity in a way, by having it, not just enjoying it but so that people can see it. I always feel if you go to visit someone’s house you’ll know more about them if you go through their music collection than by talking to them. Because music is a very emotional thing it says a lot about how we react to the world. I think cinema posters have this multiple meaning as well.

Do you remember seeing posters when you were a kid and thinking “God, I want to see that!”

Yeah, but a lot of posters promise so much that how can they ever deliver? But it was great to imagine and dream about it.

You’re interest in posters makes sense, I suppose, because you’re a very design centred director. There’s a strict sense of composition to your films.

I enjoy that. I enjoy the controlled, painterly aspect of any type of artistic expression. I like all kinds of expression. I love making lists of things, for example. I find that very entertaining. I love literature and music. It can be anything that’s personal to the person creating it that I find intriguing. I always love the imperfection more than the perfection. That’s where it assumes its own identity.

A lot of the visual influences on your films seem to come from places other than cinema. I watched Only God Forgives again last night and it struck me how influenced by gaming it is. It’s like a kind of existential version of Streets Of Rage, or something…

That’s cool. Ryan is almost like a character from a video game in that film. It’s interesting because (former (?) vice president of Konami) Hideo Kojima contacted me after seeing the movie about doing a video game, so I guess it had spoken to him. We met and talked about it. Down the line it could be a fun medium to explore. There’s a lot of innovation in games but it’s a very expensive development process, whereas with film you can just do it on an iphone to see if it works.

There’s also the influence of comic books. You have Barbarella hopefully coming up, you’ve been connected to Moebius and Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Incal…

With The Incal there’s a rights issue which makes it impossible, so it’s never going to happen. Barbarella? we’ll see. It’s still on the table, but it’s a big thing to crack. It’s interesting how much of a respected art form comics have become and how they have evolved. I find that very intriguing. And there’s the big difference between European and American comics. The European scene seems to be more intelligent, but then the Americans have the most visually striking elements.

We should get back to the book. What did you set out to achieve when you put it together?

A lot about the book is the sense of a time capsule – documenting an era that’s gone from our minds and from which the people are mostly dead. Because we’re in the era of the digital revolution we can no longer document quantity as we could. There’s so much, and so many people are making their own waves and movements and definitions that we can no longer label it. Which is great, it’s a very fresh start. But for me it’s interesting producing a book that shows what it was like – like a historical artifact. Like being in Doctor Who and going back in time. I approached it very much like editing a movie, that’s why it took so long to finish. It had to have a flow. When would it dip? When does something exciting happen? When do you surprise the Audience? I enjoyed that process a lot.

So you’re pushing abstraction toward a narrative. A film of yours like Valhalla Rising operates on an abstract and a narrative level, too.

I’m interested in making films that have subtexts. How do you switch back and forth between them? When you become less oriented around the plot the subconscious kicks in. How do you feed that monster inside people as well as coming back to plot structure? It’s like you have a skeleton and that’s the structure, but the blood needs to flow from somewhere else and that’s the heart. The heart is the subconscious

Is that tension something you look for, or is it something that appears by accident?

It’s process. From idea to the finished film. The project is not done until every possible potential of manipulating it has been tried. I don’t have much interest in result. I like to create a process.

How do you feel when you look back at your films then?

I don’t. You are forced to sit through it at Cannes, but other than that I don’t find it interesting. It’s done. I control them, but I fear watching them. It took me a long time to watch a movie like Bronson again. I have to get away from it to be able to look at it new.

Obviously soundtracks are very important to you. Do you have music in your head when you’re directing a film?

I use music as an inspiration. I try to label each of the films as a type of music while I make them and then I use that music as a reference. Music is a great inspiration. I listen to it on set a lot. I tend to be listening to music constantly.

So what was the music that went with Only God Forgives, for example?

A lot of Thai country and western music.

And Valhalla Rising?

Einsturzende Neubauten.

Yeah, I had a feeling it might be…

Drive was Kraftwerk.

What about Bronson?

The Pet Shop Boys

That makes perfect sense. May I ask what the inspiration has been for (Refn’s forthcoming film) The Neon Demon?

(long pause) …Giorgio Moroder.

Well, now I’m excited.

The Act Of Seeing is out now from FAB press