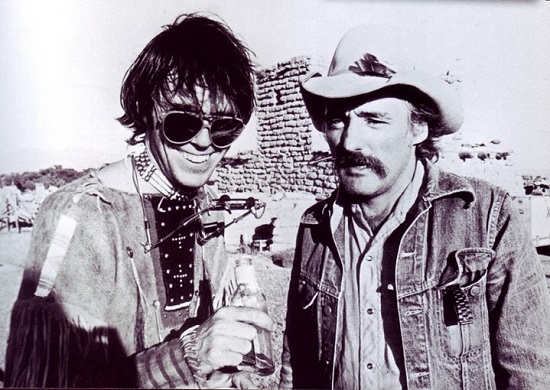

December 1985, a courthouse in Los Angeles. Sally Kirkland has filed a lawsuit against Dennis Hopper and Neil Young, relating to an incident which had occurred five years previously. Hopper had been performing knife tricks on the set of the Young’s Human Highway whilst reportedly under the influence of amyl nitrate, marijuana and tequila. The knife in question was not a dummy prop but the real thing, the result being a deep wound on Kirkland’s behalf and a severed tendon. She was suing Hopper to the sum of $2 million and seeking restitution from Young for his failure to control the actor. During the trial (which Kirkland would lose) one of the witnesses was asked what Human Highway was about. They replied: "I haven’t the faintest idea."

Young offered up a better explanation in his 2012 autobiography, Waging Heavy Peace. "It was a sort of day-in-the-life concept, all taking place in one day, just a regular day, the day the earth suddenly ended in a world war. It was a comedy." This explains the basics, but ignores the details. It doesn’t let on, for example, that Devo were among Hopper and Kirkland’s co-stars. Or former child stars Dean Stockwell and Russ Tamblyn. Or that the entire picture was filmed on an immense Culver City sound stage, giving it a look of pure artifice. Or that it flopped massively, is considered unfinished by Young and can only be viewed nowadays if you’re able to track down one of the laserdiscs or videotapes released during the mid-90s. (And you’re better off going second-hand; still-sealed copies fetch a small fortune.)

Young’s filmmaking aspirations had first seen fruit in April 1973 when Journey Through the Past premiered at the US Film Festival in Dallas. Shot on 16mm over the preceding few years it mixed up home movie-type passages with archive performances from Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, plus footage of the rehearsal sessions for Harvest. Heavily influenced by Jean-Luc Godard (his favourite filmmaker at the time), there was also room for some amateurish dramatised sections which only added to the air of self-indulgence. A scene involving shooting-up wasn’t met too kindly by the British censor, meaning we never got the chance to see the film over the here (not that Warner Bros. put any kind of muscle behind the release). Or at least not until it surfaced in the first of the Archives volumes, which is probably where it belongs: nestled among outtakes and alternative mixes, there only for the die-hards.

During its early stages, Human Highway looked as though it would become something of a Journey Through the Past Mark II. It too would be entirely self-financed by Young and, initially, filming began whilst he was on tour. Onstage footage was shot alongside backstage footage, much of which had an indulgent edge: tomfoolery on the tour bus; Young receiving a milk bath from co-star Geraldine Baron. There was also a ritualistic sequence in which a collection of cigar store Indian statues were burnt on a bonfire. All very hippy-ish, all rather directionless. However, it was also during this time that Young hooked up with Devo for a jamming session, resulting in an eight-minute version of ‘Hey Hey My My (Out of the Blue)’ with Mark Mothersbaugh in full Booji Boy get-up on synthesiser and vocals.

Young had been turned onto Devo by his then-wife, Susan. In fact, she proved integral in bringing together a number of Human Highway‘s key talents. A member of the Topanga Players, she was pally with many of the residents in the bohemian South Californian enclave. It was Susan who introduced her husband to Hopper, Stockwell and Tamblyn, all of whom were somewhat burnt-out by this point but would become firm friends. Hopper was in the midst of various addictions from which he wouldn’t properly emerge until the mid-80s. Stockwell and Tamblyn, meanwhile, had been acting since their youth (they first met when working on Joseph Losey’s The Boy with Green Hair in 1948, aged 12 and 14) but were now in a state of semi-retirement. Stockwell could count everyone from Gene Kelly to Gregory Peck as his co-stars, while Tamblyn was best-known for his musical roles: Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, tom thumb, West Side Story. Come the 70s they made just the odd exploitation pic to meet their bills, and otherwise enjoyed a simple existence.

Stockwell and Tamblyn’s association with Young extended beyond Human Highway. Stockwell had penned a screenplay with Herb Bermann (a TV actor who also co-wrote eight of the tracks on Captain Beefheart’s Safe as Milk) entitled After the Gold Rush, which proved especially influential on the album of the same name, plus he’d designed the sleeve for Young’s 1977 LP American Stars ‘n Bars. Tamblyn would later choreograph and appear in music videos as well as mastermind the series of Greendale concerts in 2003 that later gave birth to a feature-length movie and a graphic novel. Both actors also had sufficient input into Human Highway to earn themselves co-writer credits, with Stockwell receiving a co-director nod too (though his name appears a tad smaller on the screen than that of Young’s Bernard Shakey pseudonym).

The pair’s key contribution was the creation of their own characters and the dialogue to go with it. Young had visions of an all-improvised movie made up entirely on the spot, though understandably some structure was eventually applied. The earlier footage, including the Devo jam, would be reinvented as a lengthy dream sequence, with the main narrative now taken up by stranger concerns. By 1980, and to the tune of almost $3 million, Young had created a massive set on which to film his tale and the barest outline of a plot. He would play Lionel, a simple-minded garage attendant who dreams of becoming a big time rock ‘n’ roll star. The garage at which he works is in the shadow of a nuclear plant manned by Devo and has just been taken over by Young Otto (Stockwell), who has plans to burn it to the ground and claim the insurance money. Filling out the cast list are Tamblyn as Lionel’s best buddy Fred (who is also a bit of a goof, though a slightly more level-headed) and the various patrons and employees of the garage’s adjoining diner: Hopper plays the chef, Kellerman a waitress and so forth.

"Think Jerry Lewis," is Young’s instruction in Waging Heavy Peace when it comes to describing Lionel. He’s also cited The Wizard of Oz and Japanese Kaiju (giant monster) movies as an influence. They somehow conflate into a Day-Glo vision of Americana that’s oddly timeless. The cinematography (by David Myers, who’d worked predominantly in documentary) harks back to these bygone eras – Lewis comedies, MGM musicals, Godzilla pics – yet the music is all over the place. Lionel talks of Johnny Ray and the diner plays Hank Williams on the radio, but there’s also room for Devo covering folk standard ‘Worried Man Blues’ (previously recorded by the Carter Family, Woody Guthrie, Johnny Cash, et al) and providing a cut from their debut album. Meanwhile, every car in earshot is blasting out tracks from Young’s Trans LP.

Trans, of course, was one of the albums which saw Young getting sued by Geffen Records for making music "uncharacteristic of Neil Young". Of its nine tracks, six were made with synthesizers and vocoders, including a cover version of his old Buffalo Springfield single, ‘Mr. Soul’. He would later reveal that this pronounced shift in style was inspired by his son, Ben, who was born with cerebral palsy in 1978, and the communication difficulties that entailed. But at the time it was interpreted as sheer bloody-mindedness, especially when – after Geffen had requested a "rock ‘n’ roll" album for its follow-up – he delivered Everybody’s Rockin‘, a collection of rockabilly covers and some new material cut from a similar cloth. That bloody-mindedness shines through in Human Highway too, especially in the figure of Lionel, who was deemed by many who attended test screenings to be box office suicide. After all, who would pay to see Young play a complete idiot?

More from Waging Heavy Peace: "It is the dorkiest damn movie ever made and it walks a very fine line right on the edge of being too dorky. Some may say it falls over that line."

He’s not wrong. Human Highway often falls over ‘that line’. The air of improvisation and emphasis on goofiness means that much of the humour, however off-the-wall, feels a touch strained. Young includes some great sight gags and the some nicely judged sequences, but there’s no denying how wayward the whole thing is. And yet it fascinates for much the same reason: the bizarreness of it all; the odd mix of Hollywood child stars, fuck-ups like Hopper and the equally off-the-wall charms of Devo; the way in which it plays out like an alternate David Lynch movie (who would later nab Stockwell and Hopper – and the oversaturated cinematography – for Blue Velvet, and Tamblyn for Twin Peaks). At its best, Human Highway can be wonderfully infectious, as with the show-stopping reprise of ‘Worried Man Blues’ that closes the picture and sees Tamblyn choreograph the entire cast through a pull-out-all-the-stops musical number. At its worst, it’s an indulgent mess, though one that has enough in its favour to warrant at least one visit.

After the credits have rolled, the viewer is invited to "Watch out for Human Highway II". It never materialised, but then Young has never considered Human Highway to be a finished product. The version that played to San Diego test audiences in 1982 was different to the one which officially opened in 1983 which was, again, different to the one that emerged on VHS and laserdisc in 1995. Bringing up the film on a number of occasions during Waging Heavy Peace, Young insists that he is excited to be working on a final edit once more, this time intended for the Netflix and Blu-ray crowd. "I think it will still get panned," he states, though I wouldn’t be too sure. Whilst it’s unlikely to reveal itself as a forgotten classic, no matter how much of reworking it receives, Human Highway certainly has the potential to become a bona fide cult favourite.