There is a moment in Michael Haneke’s latest film, Amour, in which the wife, whose name – as in every Haneke film – is Anne, begins to utter a single word, "mal", over and over again. Seeing the evident distress this causes on the face of Anne’s husband, whose name – as in every Haneke film – is Georges, the nurse comfortingly says, "Don’t take it to heart. They usually say something." Implying: it’s normal, don’t think about it. "She could just as easily be saying ‘mum’."

In the English subtitled version of Amour, "mal" is transcribed as "hurts" and given the situation – an elderly women, paralysed and helpless after a series of strokes – this seems the logical, sensible choice of translation. But if, as the nurse implies, Anne’s choice of word (though not, of course, Haneke’s) is as good as arbitrary, we might just as well consider the other common meaning of this French word: "evil".

What do we think of when we consider the question of evil in relation to the films of Michael Haneke? I suspect that for most people familiar with his oeuvre, one of the first things that will come to mind is the face of Arno Frisch, turning to the camera with a smile and a wink in 1997’s original Funny Games. This is a wink which, like Shakespeare’s Iago, invites you to share in its schemes and, in so doing, implicates you as accessory; an evil which charms and immediately makes you feel guilty for being so charmed.

Frisch’s character, Paul, repeatedly makes a mockery of the notion that such malevolence should have some pat sociological explanation or motive. ("Why are you doing this to us?" asks another George. "Why not?" Paul replies). The two tormentors are clearly not from the ‘wrong side of the tracks’ as it were, not ill-mannered or ill brought up in the way traditionally understood by bourgeois parents. Indeed, they are polite almost to the point of pastiche.

This excessive politeness is shared by another group of tormentors in a later Haneke picture, The White Ribbon. As in Funny Games, the arch, high manners of the children are commented on by the main protagonist the first time we meet them. The White Ribbon also shares with Funny Games a scene, in both cases roughly three-quarters through the running time, in which prayer is associated with deep feelings of shame.

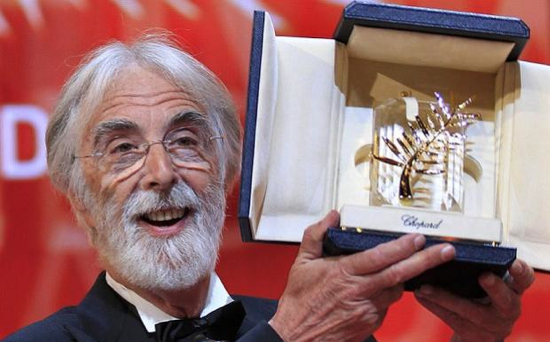

At his Cannes press conference in 2009, Haneke claimed that The White Ribbon (which went on to win the Palme d’Or) was about "the origins of evil" and, as is often pointed out, the children who appear to be at the root of the series of misfortunes which befall this quiet German village are of the right age to become the "Nazi generation". It is important to remember, however, that the movie also presents characters – perhaps just a few years older or younger than the ‘bad’ children, for instance, Eva (played by Leonie Benesch) and Gustav (Thibault Sérié) – who exhibit an almost saintly benevolence.

The White Ribbon has little of the ultraviolence of Funny Games and is in comparison a remarkably stately and slow-moving film, oblique and uneventful for long stretches of time, with a directorial style characterised by long, slow takes. Given the context already alluded to, we are reminded of Hannah Arendt’s characterisation of NSDAP functionaries like Adolf Eichmann in terms of the "banality of evil". As Arendt observed of concentration camp guards, Haneke’s ‘evil’ characters are not fanatics or sociopaths – in cinematic terms they could scarcely be further from the over-the-top supervillains of Bond films or the Hannibal Lecter-type psychos of most thrillers – but rather ordinary people in situations in which inhumanity has become normalised.

Comparing the work of Haneke with that of a superficially very different director, David Lynch, York University film studies professor Temenuga Trifonova remarked that, "Haneke and Lynch are masters of the uncanny – particularly the uncanniness of the banal and the everyday when it is decomposed, taken out of context, deprived of motivation, purpose or function – although Lynch develops the uncanny in the direction of the surreal while Haneke takes it in the direction of the super-ordinary."

When thinking of Haneke and Lynch together, we inevitably arrive at Caché (Hidden, 2005) which shares with Lynch’s earlier Lost Highway a story about a couple who begin to receive anonymous videotapes plainly showing the outside of their own house. Where the two directors take this could scarcely be more different, and their divergence illustrates very well Trifonova’s point. What is nonetheless shared in both cases is, on the one hand a temptation – practically invited by the text itself – to apply the categories of Freudian psychoanalysis. But in both cases this will only take us so far. There remain things unexplained, things which do not fit this neat schema – and both directors are almost notorious for their persistent refusal to explain their work, to say cosily what it all means and to offer this final stamp of authority over meaning.

If we think of Caché and Funny Games together (after all, Haneke himself set about remaking the latter almost immediately after the release of the former), then we are forced into the surprising conclusion that the analogue of Arno Frisch’s malevolent Paul is not Majid (Maurice Bénichou), the external force which seems to threaten the solidity of the family, nor even his son (Walid Afkir), the aggressive young man, but rather Georges Laurent himself, Daniel Auteuil’s ‘bourgeois-bohème’ pater familias. After all, it is Georges, like Paul, who has the power to rewind the tape. He has the power over final cut – ironically, a power which is reserved far more often by auteurist European directors like Haneke himself than by those filmmakers of the Hollywood production line which he is often supposed in opposition to.

Oliver Speck has commented at length on the tendency to self-reference in Haneke’s films: the video monitor which both shows and obscures the violent action at the centre of Benny’s Video (1992); the direct address to the camera in Funny Games; the endless frames-within-frames which mark his shots – whether TV screens in Caché or Code Inconnu (2000) or the doorways and window frames of The White Ribbon. But, as Speck remarks, what is most shocking is not "the alienation effect of breaking the fourth wall" but, rather, "the subtle device that brings about the shock of realising that we are not gazing at something, but with something". What this reveals, however, is not just the always partial, fragmented, irreducible nature of Haneke’s images, that there are always other points of view, other perspectives, etc. but our own guilt as spectators, our own complicity in everything which proceeds.

In an interview on the Artificial Eye DVD of Caché, Haneke recalls seeing a documentary on the French TV channel Arte about the massacre of October 17th 1961, when French police attacked a demonstration by pro-FLN Algerians in Paris, ultimately killing some 200 protesters – either beating them unconscious and herding them into the Seine, or carting them by bus back to police headquarters to be tortured and murdered by officers in the station courtyard. This massacre was covered up and repeatedly denied by the French government for four decades, only coming to light shortly before Haneke set to work on his film. How could this still happen, Haneke asked himself, in 1961? Why, we might ask, this insistence on still in 1961? What this ‘still’ means, of course, is still after the Holocaust.

Like his contemporary, the artist Anselm Kiefer (Haneke was born in 1942 in Munich, Kiefer in 1945, 300km west down the A96 in Donaueschingen), the Holocaust and the weight of history’s guilt is one of the master themes of Haneke’s work. The White Ribbon deals with this explicitly, of course. Likewise, Caché uses one man’s secret shame as a metaphor for the national secret of October 17th.

In Kiefer’s early work he employed a series of controversial performances and photographs to force Germans to confront a guilt that he felt was being elided. Haneke similarly is not afraid of using shocking means to break through the complacency of his audience. But in Haneke’s films, violence is more often something hidden by the camera than exposed by it. Even in Funny Games, every blow occurs just outside the boundary of the frame, simultaneously drawing attention to that frame and frustrating the audience’s sadistic desire for graphic violence.

Think of Benny’s Video, one of his first features, now 20 years old, in which another polite young man with his finger on the rewind button, again played by Arno Frisch, has an obsession with violent movies. But when Benny invites a girl (Ingrid Stassner) back to his room and murders her with a captive bolt pistol for slaughtering animals, the violence, again, happens just outside the frame of Benny’s video monitor through which we, in turn, are watching the events unfold.

Later, we see Benny and his mother (Angela Winkler) on holiday in Egypt, with Benny keeping a constant video diary of their travels. All the while we are made aware, without seeing it, that back home Benny’s father (Georg, played by Ulrich Mühe) is taking care of the gruesome task of covering Benny’s tracks: cutting up the girl’s body into pieces small enough to cleanly dispose of, scrubbing away every trace of blood. The camera, then, is precisely what hides the stain of guilt, of violence.

The apparently candid nature of videos in both Benny’s Video and Caché is really a veil which both hides (and in hiding, finally draws attention to) a family secret which must finally come back to haunt, in apt demonstration of Freud’s theory of the uncanny. If we are to ask then, what is the source of evil in Haneke’s films, the director seems to be leading us to the startling conclusion that evil is in cinema itself.

Amour is in UK cinemas now. Michael Haneke’s adaptation of Franz Kafka’s novel The Castle (Das Schloß), originally broadcast on Austrian television in 1997, is released as a stand-alone DVD this month by Artificial Eye.