“…like any dealer he was watching for the card that is so high and wild he’ll never need to deal another…”

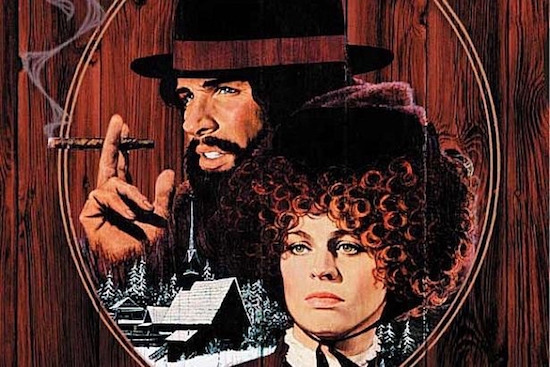

So utters Leonard Cohen in the opening titles of Robert Altman’s 1971 western McCabe & Mrs. Miller, now available in a restored Blu-ray edition from Warners. Altman may have seemed an odd fit for the Western, but a genre built on American history and myth couldn’t be more suitable for a director who seemed like he was purposely sent to shake things up. McCabe was certainly an opportunity for that, and to paraphrase Kurt Russell in Big Trouble In Little China – itself a Western in Chinese-American clothing – it really “shook the pillars of heaven” as it eschewed a traditional score for the laconic poetry of Cohen.

Of course, songs had already been an incredibly important part of Westerns – the campfire sing-along writ large as the main title. Subsequently you have True Grit opening with Glen Campbell crooning the words of Don Black to the music of Elmer Bernstein, and Frankie Laine musically explaining the story of Gunfight At The OK Corral, not to mention Tex Ritter’s High Noon, the latter pair with lyrics by Ned Washington and music by the great Dimitri Tiomkin. But these pictures had full scores as well – no-one had “just used songs”. But by the time the seventies rolled around, the Western had just been through a revolution of its own with the creation of the Revisionist Western, where the West was not only wilder than ever but also now reflecting on its own existential crisis. The life of a cowboy was no longer the pure-heart white hat whose actions were always lawful and true.

The sixties was a long and often painful gestation period for the Revisionist Western, not least because it saw the rise of the enfant terrible of the genre, Sam Peckinpah, whose Ride The High Country (1962) and The Wild Bunch (1968) ostensibly bookended the decade, the former exploring the dimming idealisation of the genre, the latter its nihilism. McCabe came in right after a change of pace for Peckinpah – the charming The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970) – and both share similar qualities: the partnerships of Warren Beatty’s McCabe and Julie Christie’s Mrs. Miller next to Jason Robards’ Hogue and David Warner’s Joshua, the former running a brothel, the latter a water spring, with both representing the evolution of the West as it moves from the old world to the new. Like McCabe, Cable Hogue also features a set of wonderful folk songs, in this case by Richard Gillis and Jerry Goldsmith (who also wrote the gentle score).

However, with McCabe, Altman helped the genre evolve further by using songs that had already been written, in the case of three songs taken from Cohen’s 1967 album Songs of Leonard Cohen, namely ‘Winter Lady’, ‘The Stranger Song’, and ‘Sisters of Mercy’. Altman was a fan of the record already and stated he used to put it on while high, and suddenly remembered it while editing, while Cohen allowed the use of his songs because of his love for Altman’s Brewster McCloud (1970). The film’s soundtrack isn’t limited to his songs – it includes fiddle by Brantley Kearns and guitar by David Lindley, who as part of the band Kaleidoscope played on Songs, as well as the twinkly Brahms that comes from Mrs. Miller’s music box – but it belongs to them.

‘The Stranger Song’ opens the film and immediately blends with the soft and dreamy photography of Vilmos Zsigmond to create something markedly different for the genre that now feels as valid and classic as anything by Bernstein or say, Jerome Moross. Interestingly, the film version of the song features an extended instrumental section by Lindley, described by critic Robert Christgau as “a long, elegiac, Spanish-tinged”. Cohen’s lyric here – “He was just some Joseph looking for a manger” – is a great introduction for McCabe, and has the glint of subversion that was always a trademark for Altman’s pictures.

‘Sisters of Mercy’ introduces McCabe’s prostitutes and notably the male reactions, the gawping construction workers and McCabe’s own shyster approach to it all that comes to a head when Alma stabs one of the punters. Cohen’s music just lingers as it’s clear McCabe is in over his head, and it’s no coincidence that this immediately precedes the arrival of Mrs Miller. Mrs Miller’s theme is ‘Winter Lady’, and we first hear it echoed in her smoky yellow room, post-opium session, but it’s used beautifully when she stands outside in the falling snow, scared at the inevitable fate of her and McCabe, Cohen uttering “you chose your journey long before you came across this highway”.

The final gun battle is almost devoid of sound entirely, the quiet wind punctuated by the ear-shattering shotgun blasts. No music at all and surreally serene, despite a church being set on fire – it’s only when the town notices do we hear a cacophony of shouting as everyone runs for ice, along with the movement of the locomotive. ‘Winter Lady’ plays again at the climax, cutting between Mrs Miller’s opium-sedated face and McCabe’s dead body in the snow, before Altman zooms into Christie’s haunted eye.

Two months after McCabe, another Revisionist Western scored by a celebrated musician trotted into town in the guise of Peter Fonda’s The Hired Hand. Advertised as “Peter Fonda is riding again…” to capitalise on the success of Easy Rider, it received a gentle and understated score by Bruce Langhorne, who had worked with Bob Dylan amongst others. His working relationship with Dylan would interestingly coincide in 1973 when he worked on Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, which Dylan was tapped to score to the disgruntlement of Peckinpah’s regular collaborator Jerry Fielding, although he would brilliantly score the director’s next picture Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974).

Both Dylan’s score and songs for the film are superb, with his guitar work sounded decidedly less anachronistic as it might. However the centrepiece was, and still is, ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’, seen in the film as Slim Pickens’ Sheriff Baker and his wife wait for the inevitable after he’s shot. Both The Hired Hand and Pat Garrett were critical failures initially, but have gained new reputation as masterpieces since being released on home video. Another film released at the same time was 1972’s Buck and The Preacher. Capitalising on the success of recent ‘blaxploitation’ films like Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song and Shaft, Buck and the Preacher is a revisionist western both in terms of its approach to the genre but also because of the way it used not only an African-American cast but also African-American music for its soundtrack. Directed and starring Sidney Poitier, the film also featured Harry Belafonte and had a jazz score by Benny Carter, who had previously arranged recordings for the likes of Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday.

Before long, partnerships were being struck up, such as Walter Hill and Ry Cooder, who began their work together on the 1980 Western The Long Riders, which featured many real-life Hollywood brothers as siblings from American history, with Stacy and James Keach as the James’ brothers. Hill would go on to make many neo-Westerns in his career with Cooder scoring, such as Streets of Fire, and Last Man Standing. The Clash frontman Joe Strummer had a similar if shorter relationship with Alex Cox (of Moviedrome and Repo Man fame), with one of their collaborations the 1987 Western Walker, scored by Strummer with a Reggae influence.

And it continues today. Famous contemporary examples include Antonia Bird’s Horror-Western Ravenous (1999), which saw Blur’s Damon Albarn working with composer Michael Nyman, while the obvious choice would be Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, who have scored a fair number of both Revisionist and Neo-Westerns. John Hillcoat’s The Proposition (2005) was the first attempt at the genre from the pair, and their stirring and gritty score led them to films like The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and Hell or High Water, and it’s no surprise they’re held up in such high regard given the sheer quality of their scores; beautiful and evocative, and always hauntingly melancholic.

But the lightning strike that was McCabe & Mrs. Miller is still here, in a fresh digital restoration that looks gorgeous. The softness of Zsigmond’s photography may seem like it lacks detail, but it’s just part of his technique. Cohen’s songs sound incredible, and it features a neat ten-minute period documentary as well as an informative commentary by Altman and producer David Foster. There’s never been a better time to hunt this one down.

McCabe & Mrs Miller is out now on blu-ray