Bullets Of Justice, which showed at this year’s Mayhem Film Festival

Day One

You’ll maybe want to imagine an orchestral stab or a muffled slamming noise as the words ‘Day One’ intrude on your internal screen. Zombie references are definitely appropriate as I write: Mayhem Film Festival is a four-day marathon of contemporary horror, sci-fi and cult film, with its longest day clocking in at over 12 hours of premieres, screenings, Q&As, quizzes and interviews, and pauses barely long enough for a pint. Red eyes are standard, OK?

I’ve attended at least one day of Mayhem every year since I moved to Nottingham five years ago, and this was the second time I have wrestled my way through the entirety of the festival. I have this in common with a growing number of enthusiasts – Mayhem does everything it can to make watching the worst things humankind can imagine into a treat, and aims for accessibility above all (knowing your genre ABCs is very much not required). There are many friends I only see at this event, people from elsewhere in the folded-down industrial infrastructure of the East Midlands, but also from further in the UK and abroad. This year I was with my wife Sophie and our friend Emma, who travelled from Sweden via Finland to stay with us for the festival. Sophie and I first met Emma in January, at a hotel in Marbella which caters on-season for the TOWIE crowd, but has a winter sideline providing rooms for trans women attending a nearby specialist hospital, and for football teams at coastal training camps. Sharing a breakfast buffet with stoical women in various stages of surgical recovery I had expected – that’s what Sophie was there for too – but I’d not predicted the presence of the entire Standard Liège side. Allez les rouges! Bunch of cuties.

Mayhem, as far as I know, has no plans to offer facilities to the Belgian First Division, but is no less hospitable an experience for that. It takes place in Broadway Cinema, a former Wesleyan church that housed the Nottingham Film Society from 1959 onwards, re-developed in 2006 into the deco-inspired light box of its current incarnation. The Broadway building’s lambent modernity and the calm sweep of its terrace beam out leisure among the busy Victorian frontage of Hockley. Broadway’s staff are intimately involved with Mayhem, from programmers and projectionists to the bar and kitchen, which offer themed food and guest beers and ciders in the ghoulishly-lit cafe bars (transformed within hours from the genteel tea and biscuits of the Thursday morning Silver Screen). The entire cinema is given over to designer Dan Lord’s gory, sigil-heavy aesthetic for the duration of the festival. Picking up our passes we’re greeted, as are all festival-goers, by the organisers; lecturer and writer Chris Cooke, Broadway film programmer Melissa Gueneau, and filmmaker Steven Sheil, whose kindness and hospitable engagement with their audience is key to the festival’s philosophy.

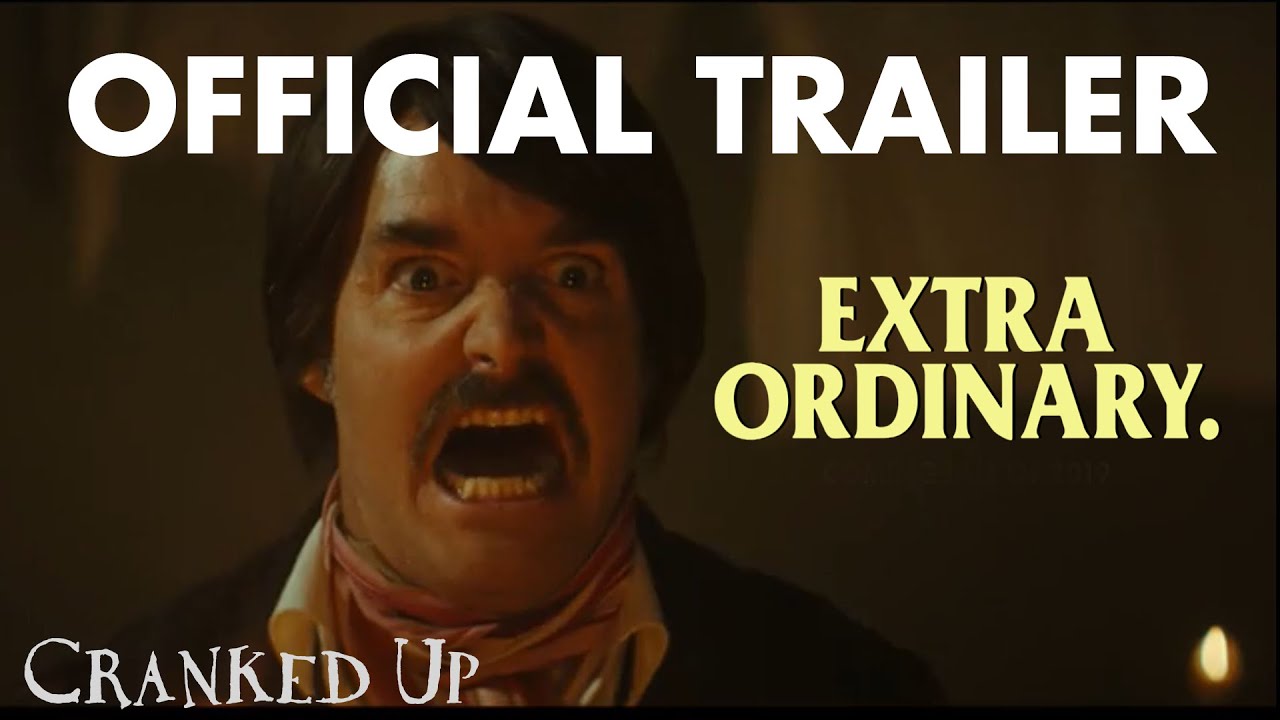

The first evening’s line-up begins with the hilarious Extra Ordinary (2019), a debut horror comedy from Irish writer-directors Team Daddy, whose lead performance from Maeve Higgins as retired child psychic and driving instructor Rose Dooley is nothing short of delightful; I’m seriously infatuated with this character, and I very much hope to see her again (ideally for a driving lesson). The only title this weekend to boast its own Soundcloud channel, Extra Ordinary blends perfectly observed Irish character comedy with occult histrionics in the Wheatley mould. Not always effectively – a couple of the jokes misfire a little, particularly the possession of Barry Ward’s Martin Martin by his wife Bonnie, a swishy turn that’s somewhat out of place in such an otherwise sweet-natured film. The climactic scene too feels less unhinged than daft, but it’s all pretty forgivable given the fun the writers and cast are evidently having; I laugh out loud, a lot, from start to finish, where in my daily life I am more likely to murmur "lol". After the showing, co-director and single Daddy Mike Aherne joins us for a Q&A (I can exclusively reveal that while he does not himself believe in ghosts, he knows people who do). Following its deservedly warm reception at Mayhem, the film is set to return to Broadway for Halloween.

Also a first night stand-out is Adam Egypt Mortimer’s Daniel Isn’t Real (2019), with Patrick Schwarzenegger in the title role: a Bateman-esque performance worlds away from his lead in last year’s maudlin Midnight Sun. The film has garnered praise for the performances of both Schwarzenegger and co-lead Miles Robbins, as well as its clever writing. But for me, it’s the design and effects that are most powerful. The storyline focuses on Luke (played by Robbins with studied art-brat sulkiness), whose imaginary childhood friend Daniel re-emerges to increasingly violent effect following the breakdown and hospitalisation of Luke’s mother. Set in a beautifully shot New York, the narrative attempts to balance a psychological reading with the possibility of more cosmic forms of mayhem, though is stronger when exploring the latter (and may leave some viewers queasy at the implied relationship between mental illness, trauma and violence).

Boundary issues: Patrick Schwarzenegger encroaches on Miles Robbins in Daniel Isn’t Real

Brought to screen by the producers of last year’s extraordinary Mandy (think Taken on very bad mushrooms), Daniel Isn’t Real is similarly good to look at, with very effective use of colour to convey the increasing contrast between internal and external realities. While ostensibly drawing on doppelganger and possession genre fodder, Daniel Isn’t Real also has clear affection for psychedelic point of view noir such as Requiem For A Dream and Memento. The film aims for empathy alongside demonic world-building, and doesn’t quite succeed – the ending feels a little drawn-out and incoherent in its attempts to show enough of both. But this is a visually appealing modern horror, coming to theatres in early December.

Day Two

Every year, Mayhem is at pains to offer international and historical genre films at this point in the programme; 1967 folk horror Viy is a feast of period filmmaking, a grim Soviet Wizard of Oz. Based on the novella of the same name by Nikolai Gogol, and set in a rural seminary at some point in the pre-communist past, Viy uses beautifully painted sets, a full orchestral score and surprisingly inventive special effects to convey the gradual devastation of a young monk, Khoma, by a witch he foolishly provokes while out carousing with his fellow novices (despite Gogol’s own strongly-held religious beliefs, Soviet directors Konstantin Ershov and Georgiy Kropachyov are clearly Team Witch, and fittingly unabashed about showing the monastic tradition as purest hypocrisy, in thrall to feudal powers and prone to violence and exploitation). With lengthy bucolic interludes, drunk cossack dancing and plenty of impromptu folk singing preceding the eventual infernal havoc, this gem of a film is available from Severin Films and deserves your immediate attention.

Comrage: Natalya Varley as Pannochka in Viy

Similarly cynical about its country’s religious history, but tonally light years away from the fantastical Viy, is Polish drama Sword Of God (The Mute) (2019). Directed by Bartosz Konopka, whose allegorical short documentary Rabbit à la Berlin, tracking the lives of bunnies within and, finally, beyond the Berlin wall, attracted an Oscar nomination in 2010, Sword of God sees its UK premiere at Mayhem. Konopka’s unrelentingly brutal, weirdly alienated religio-historical drama, a tale of two Christian knights at pains to convert a pagan mountain community, somehow fails to convey much more than the vicious banality of the colonial project, despite some stunning location cinematography and an excellent score from Jerzy Rogiewicz. The film’s attempts at conveying pre-Christian social and emotional ways of being verge on the facile; humans sleep and wake together in piles of undifferentiated pagan bodies. The film’s saving grace is its refusal to turn away from the genocidal legacy of the Catholic Church, which I suspect plays very differently in Polish theatres than it does at an East Midlands festival full of horror geeks.

Genre film enthusiasts we may be, but Girl on the Third Floor (2019) is a genre bent too far, a haunted house with several inhabitants too many to manage. Initially, the film’s central conceit – that its would-be family man, Don (played by CM Punk in his debut lead role), is an absolute dickhead – is refreshing to watch. Then the film decides it’s less about the intrinsically haunted nature of modern masculinity, and more about your toothy zombie demon doll. Oh, and about the ghosts of suburban sex workers, and about sinister lady pastors. I don’t fucking know. Seeing Girl On The Third Floor screened at Mayhem is bemusing, since this is a festival that has represented the haunted house genre beautifully in the past. Last year’s Sunday afternoon screening of The Witch In The Window (2018) made a full auditorium of tired, jaded Mayhemites gasp with its big reveal. No effects, no monster, just a shared moment of realisation. I hope CM Punk is OK, he’s the least worst thing about this film.

Witness the shitness: CM Punk as Don the dickhead dad in Travis Stevens’ Girl On The Third Floor

Despite a late screening of The Hidden (1987) to look forward to, Day Two effectively ends for me with the existential horror of Color Out Of Space (2019), Richard Stanley’s return to directing after a 27-year hiatus, offering an interpretation of the Arkham classic, made and remade regularly in the last decade. Stanley’s version overlayers Lovecraftian lore with a thoroughly contemporary climate anxiety, and genre favourite Nicolas Cage reins it in just long enough to make the family relationships believable, before delivering a fittingly apocalyptic second half. Despite the film’s B-movie and splatter references, the tension Stanley manages to build, the wyrd disconnection the family endures before understanding the world is coming apart, are grounded enough in sci-fi horror and each well conveyed in performance and in design (particularly sound design, with Colin Stetson’s score taking much of the credit). More than anything, Color Out Of Space is generous – so much detail, so much saturation – and the Mayhem audience responds equally affectionately, particularly to Cage. The film will inevitably draw comparisons to Alex Garland’s relatively pious Annihilation (2018), but Color Out Of Space manages a sense of threat throughout, despite its cornier moments, without ever taking Lovecraft too seriously.

"They’re alpacas, Lavinia, okay?" Nicolas Cage faces down a cosmic threat in Color Out Of Space

Day Three

Having been warned by a friend that it contained some distressing scenes of animal suffering, I decide to skip the morning showing (a UK premiere) of The Pool (2019), Ping Lumpraloeng’s nail-biting survival horror, in favour of having my first ever contact lens fitting. Giddy with unaccustomed clarity, and with that holiday feeling that workaholics get when we flake, I also skip Audrey Cummings’ She Never Died (2019), an interesting-looking zombie cannibal mashup with Olunike Adeliyi in the lead, as it includes scenes on a snuff movie set. Both these titles look appealing, especially She Never Died, which promises a darkly comic companion piece to 2015’s He Never Died, cult favourite starring Henry Rollins – and skipping them isn’t a judgement on their makers, I just know when stuff is not for me.

Catching up with Sophie and Emma back at Broadway (Sophie confirms with a wide-eyed nod that I made the right decision), I consider skipping After Midnight (2019) too. On paper, I’m not the ideal candidate for a mumblecore monster breakup film whose lead character is some sad sack Floridian shooting deer for his jollies and crying into his PBR. I settle reluctantly into my seat, and am swiftly and joyfully won over.

After Midnight‘s appeal is difficult to describe. It’s a monster movie, and a breakup movie, and it’s an effective example of each of those separate genres as well as using one as an allegory for the other. It’s the emotional heft of the writing and performances, in part, that make this possible: co-director Jeremy Gardner plays the lead, Hank, enduring heartbreak that’s truly distressing to watch, the kind that can turn your bed to bones and make you believe you’re cursed, hunted, singled out for despair by malign forces. When he starts to encounter those forces at his door in physical form, Hank is torn between confronting himself and hunting the monster outside. Gardner and co-director Christian Stella, a long-time collaborator also on board for 2012’s The Battery (a zombie/buddy movie mashup similarly concerned with relationships in the context of existential threat), take their time – it’s fully possible, as a viewer, to forget you’re waiting for a monster – with daringly long static shots and extended, slow dialogue. A particularly lovely scene is the dreamlike conversation between Hank and his girlfriend Abby (Brea Grant) at the door of the house, a single shot lasting several minutes. A meditation on the monsters we create by not loving well, After Midnight is the unexpected hit of the festival – in dozens of conversations, I never encountered anyone who didn’t like it, and the Mayhem team rhapsodised about it. If this particular monster scratches at your door, let it in.

u ok hun? Hank (Jeremy Gardner) faces the music in After Midnight

Pausing only to fail once again at winning an A0 poster of The Human Centipede 3 – Mayhem is peppered with pop quizzes, and these posters, left over from the film’s UK premiere at Broadway, are always the prize – I prepare myself for the treat of the weekend. Mayhem’s short film slot – two hours of the best horror, sci-fi and cult film shorts around, in live-action or animation, many of them UK or world premieres – is sourced by Melissa Gueneau from many dozens of local, national and international entries, and is the section of the festival where I most often encounter the unforgettable, the unpalatable, and the simply inexplicable. This year’s standouts include Vidar Aune’s Creaker, a haunting with an exceedingly gory twist; NOM by Angel Hernandez Suarez, a beautifully shot modern vampire short; the tensely claustrophobic Unmade, by Mayhem’s own Steven Sheil; Andrew Hunt’s calmly devastating Alaskan zombie short, Frost Bite; Charles Thurman & Neal O’Bryan’s Toe, a Švankmajerian romp through a frankly revolting folk tale; and Wild Love, a perfect macaron of love, death, revenge and prairie dogs, by Paul Autric, Quentin Camus, Maryka Laudet, Léa Georges, Zoé Sottiaux & Corentin Yvergniaux. Special mention also goes to Calvin Lee Reeder’s The Procedure Part 2 and Kate McCoid’s It’s Not Custard, both of which made me actually retch. At this point in the evening, too, I attempt for the first time ever to take out my new contact lenses, which results in my almost peeling off the membrane of my right eye while my wife looks on aghast. I don’t hold Mayhem responsible for that exactly, but it doesn’t feel entirely out of keeping. Should you wish to take a moment to imagine me carefully tearing off the jelly-soft flesh of my eye in ultra slow motion, accompanied by this lovely rendition of Handel’s Laschia Ch’io Pianga, please go right ahead.

Day Four

Steven Sheil and Chris Cooke describe Sunday morning as the festival’s ‘what the fuck’ slot, and agree that Valeri Milev’s Bullets Of Justice is their what the fuck-est presentation to date. More than usual, this year’s Mayhem has avoided screening straight genre films in favour of mashups and detournements, but Bullets of Justice is another creature entirely. High camp, gore, action and fantasy, fearlessly disgusting and with a twist no sane person would see coming, it’s not for the faint of stomach. Incestuous mercenary siblings Rob and Lena carve their way through a post-genocidal society of mutant pig supersoldiers which now farm human flesh. There are gasping, ragged plot holes here – at times the film feels unfinished, so much is left unresolved, possibly due to its provenance as a video series – and yet it is constantly entertaining, and leaves me seriously considering growing a handlebar moustache.

The gleeful carnage of Bullets of Justice could not be further removed from Kwon Lee’s thoughtful, skin-crawling survival horror, Door Lock (2018), here seeing its UK premiere at Mayhem. Door Lock is a South Korean reinterpretation of Spanish stalking thriller Mientras Duermes, which is told from the perspective of the stalker, Luis Tosar as the tortured, violent Cesar dominates the screen, and his struggles and motives are the true subject of the film. Featuring outstanding performances from Gong Hyo-Jin as stalking victim Kyung-Min and Kim Ye-Won as her ebullient best friend Hyo-Joo, Door Lock has entirely different aims from those of its Mediterranean antecedent.

This is a movie refreshingly uninterested in the motives behind violent misogyny. In an implicit rebuke of its predecessor, it presents the ordinary scrutiny of women by men as a pervasive form of surveillance, treating institutional sexism as an equal threat to the more explicit violence Kyung-Min also experiences, and offering a particularly scathing portrayal of the police response to male violence. While Door Lock‘s themes are patriarchy, security and technology, its principal subject is fear: the camera focuses closely on Kyung-Min, alternating between long shots of her in corridors or alleyways and close ups of her face as she wrestles with everyday anxiety or immediate terror, the scenes of friendship and solidarity between Kyung-Min and Hyo-Joo are the film’s only hopeful moments. It’s a tough watch, particularly for suvivors of stalking, domestic abuse or sexual violence. Following the film, I find several shaky and tearful people in need of the comradely affection only the toilet queue can bring. Door Lock is an astute and suspenseful thriller with plenty to satisfy fans of the genre, but its real strength lies in its sympathy and respect for survivors, and in its understanding of structural violence. More of this please, at Mayhem and elsewhere.

Call me ACAB: Gong Hyo-Jin as Kyung-Min in Door Lock

Mayhem in its own words: festival directors Chris Cooke and Steven Sheil and programmer Melissa Gueneau discuss the festival’s history, legacy and future ambitions

Having attended Mayhem a few times now, some clear themes emerge in your programming each year. What do you see as emerging themes this year, and how do they reflect what’s going on in horror, sci-fi and cult filmmaking at the moment?

Steven Sheil: I think this is a really interesting time for genre films – there are a lot of people who are twisting horror into new shapes and even redefining what we mean by horror. We’re seeing a lot of films that have horror/sci-fi aspects to them but which don’t follow traditional genre narrative lines – I think both Daniel Isn’t Real and After Midnight would fall into that category.

I’d have to say that one emergent theme is masculinity. A lot of the films we saw this year touched on notions of male relationships, whether that be romantic or sexual or familial and I think part of that is that it’s a bigger conversation in the world currently. In terms of how they’re used in horror, men are both something to be afraid of, and subject to a lot of fears and anxiety about their place in the world, and I think it’s really interesting that those questions are being tackled.

Which of these films were you each personally most excited about bringing to Mayhem?

Chris Cooke: There are many, especially some of the smaller, less hyped films, but Color Out Of Space for me – I like Richard Stanley and it has been a long time (27 years) since a new feature film… HP Lovecraft is a really fascinating writer and Nicolas Cage is a fan-favourite, so we were delighted to be able to put the film in front of our audience so quickly after the UK premiere. That and the Russian classic, Viy – any film with coffin surfing is a winner for me.

SS: Color Out Of Space was a big one this year, definitely. But sometimes the films I am most excited about bringing to the festival are ones with moments that have shocked or surprised (or maybe even appalled) me, because I want to have that experience of seeing them with a crowd. In those terms, The Pool and After Midnight were probably the ones I was most excited about presenting.

Melissa Gueneau: The Pool was probably the one I was most excited to put in front of an audience. I reacted so strongly to it just watching it on my own that I couldn’t wait to see how 200+ people would respond together … and it didn’t disappoint! I just love to see everyone go through the rollercoaster of emotions we put them through for just under two hours.

The short film section has been the highlight of Mayhem for me over and over again, as that’s often where I first encounter fresh horror talent. Can you talk about the short film production and selection process, and (for anyone considering entering) what you look for when you’re making the choices about what to show in this section?

CC: We started out as a short film festival, 15 years ago – Nottingham needed a platform and space, not just for new talent, but for emerging genre filmmakers specifically.

MG: I’ve been overseeing the shorts submissions for the past five years now. We receive more and more films every year, from more and more countries, and the quality gets higher and higher every year too, which makes it harder for us, but that’s only a good problem to have.

Most films come to us organically, but I also get in touch with specific groups and filmmakers to make sure they’re aware they can submit their film. We want to be able to offer a diverse mix of films, stories, styles, and voices; and we also want to have local/regional, national and international titles. We do have to consider how the films will fit alongside each other and find a way to make the programme cohesive and diverse all at once – it is essentially the soul of the festival.

If someone has a short they want to submit, I’d say just go for it. As long as it’s within our realm of horror, sci-fi, cult and the edges of it all, I almost definitely want to see it.

There’s a large number of people in the Mayhem audience who come every year. After 15 years, do you feel you know your audience? Do we ever surprise you? When you’re watching with us, do you feel part of the audience or do you feel somehow ‘with’ the film?

SS: I’d like to think that by this point we’ve got a good idea of what might work for our audience but it’s also a two-way thing – we get a lot of people who buy passes for the entire festival before we even announce any films.

I try and make an effort to be in for films, or moments in films, where I really want to see and hear the audience reaction, because that’s one of the things that makes it all worthwhile. Hearing a big laugh or a loud gasp or a general moan of disgust is great because it tells you that the film is working the way that it should and the way we hoped. In those instances I guess we’re slightly outside the audience – because we know what’s coming – but there’s a real sense of gratification about knowing that you’ve given people a memorable moment, because that’s what got us into the genre in the first place – those moments.

Do you feel Mayhem is gaining a reputation in the UK film festival scene? What particular role does it play, what do you feel the festival does best?

CC: I think the reputation has built around the programming and the venue – we have a great location for the festival, it is welcoming, inclusive, creating a perfect base for audiences to relax and get to know the films and to say hello to each other, make friends, etc. The programming has grown in reputation because we can be quirky, take fans off the beaten track, curate things across each day, introduce them to new talent and of course, screen must-see titles.

SS:I hope that the festival has a reputation for being open, friendly and welcoming. Even though we’re showing the wrongest stuff imaginable, our crowd are very friendly and polite and generally good-hearted and I hope that comes across to newcomers. We want people – whatever their background or relationship with horror – to feel like they’re welcome. There’s no entry requirement in terms of fan-knowledge about the genre and we try and make it as fun as possible, maybe especially because we’re offsetting what’s happening on screen. Horror is great for catharsis – it deals with bad thoughts and bad happenings and a festival like ours gives a space to process those things, so we want to make it as welcoming as possible so that people can live out their bad dreams on screen in comfort.

The 2019 Mayhem Film Festival ran 10-13 October