Mmm, hang on. I’ll be with you in a minute. I just have to get a can of Marley’s Mellow Mood out of the fridge. I keep it in there, next to the Reggae Reggae Tomato Ketchup. It says on the tin that it’s a herbal concoction, and in this case, the Jamaican pronunciation is spot on. Maybe I should put my African Apparel t-shirt on, the one that says ‘BOB MARLEY’ above a picture of Jimi Hendrix. I can’t work out if it’s a pointed comment on racism or just knowingly offensive. I guess I’d get biffed on the conk if I wore it in some places, though whether that’s the grimmest of Third World slums or a Western dinner party is moot. That’s the thing about dead pop stars. They always mean something to someone.

Involuntary association with unlikely merchandise is the price inevitably paid by secular saints (and, come to think of it, by religiously recognised ones too). I used to check the temperature of my daughter’s bath with an official John Lennon water thermometer, always wondering just when Yoko’s people signed that one off, possibly accidentally. No wonder it cost a pittance at TK Maxx.

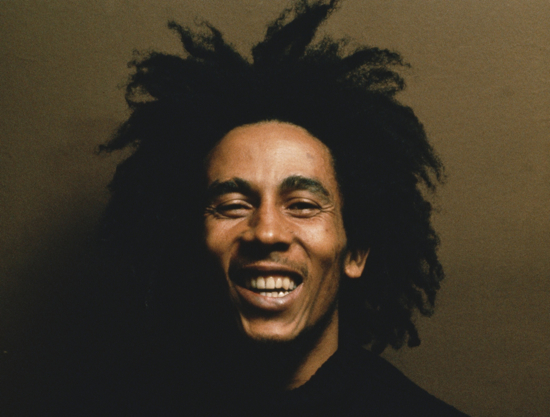

Three decades since his sadly premature death, Bob Marley isn’t far behind as a universal symbol. Weed holes in Amsterdam and walls in Africa bear his name and image: Marley is a greater, weightier presence today than he ever was when alive, and he was big then. I remember. After catching this in a Soho preview screening room, I passed an approved Tube busker playing ‘Three Little Birds’, the same tune a gaggle of schoolgirls had treated a Hackney bus to a week before. Whether tobacco giants Philip Morris really did register the name ‘Marley’ in preparation for the inevitable legalisation of cannabis is irrelevant. Everyone recognises and understands the connection. Even rumour salutes him.

So we forget that he chose to follow the traditional music business pathways to stardom – hard touring, selling his songs to other performers, letting the record company have their way even – while his original Wailer cohorts, Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston, rejected the machine. (Tellingly, the outside musicians Island Records head Chris Blackwell hired to add radio-friendly overdubs to Catch A Fire were heavyweights, like Wayne Perkins and Rabbit Bundrick – the machine was running at full power, obviously.) Marley was ambitious, not saintly. He knew exactly what he was walking into. Even at the end of Kevin Macdonald’s enjoyable documentary, when its subject’s cancer had spread so far he could no longer work, the US tour sacrificed is a double-header with the Commodores, lucrative not epochal.

Maybe he was starting to reach the black American audience he’d always craved, having already been adopted by a white college crowd. This though is the stuff of mere careers, and Marley, despite himself, is more interesting than that. He might have been as much of a cocksman/sexist pig as any of his privileged white contemporaries, yet in truth he was a chip off the old block too. His absentee father Norval Sinclair Marley, of mixed-race background but considered white in colonial Jamaica, certainly liked to play around. There’s a telling scene where wife Rita recalls a visit to a laundrette where she fell into conversation with the manageress, another Marley, who turned out to be Bob’s previously unsuspected half-sister.

If Marley fancied the straightforward life of a star, it was never going to happen, at least while he stayed in Jamaica. "I’m bringing the ghetto uptown," he joked, living in Kingston’s flashiest enclave with an endless selection of hangers-on, well-wishers and ne’er-do-wells in tow. He was as much a cacique, a local bossman, as a musician, his benediction (and contribution) sought by many. No wonder he managed to shame Michael Manley and Edward Seaga, rival white politicians ultimately in charge of feuding gangs, into a public handshake on his stage. He had big brass balls, no mistake, surviving an assassination attempt that forced him into London exile. (Without that bullet there’d have been no Punky Reggae Party. Clearly, Jah is a vexing master.)

From then on, he belonged to the world, a world which sometimes didn’t really understand its new possession. When he played at the April 1980 Zimbabwe independence celebrations (off his own ticket), a police-fomented riot broke out. Yet he retained some humility and humanity; it makes for a fascinating comparison with James Brown’s trip to Africa in 1974. (Although Mugabe was far from the dictator we know now, Marley performed for some proper villainous presidents too – maybe musicians are just resigned to working for crooks).

As for the film, Macdonald, who was the third director attached to the project after Martin Scorsese then Jonathan Demme dropped out, has a limited archive to work with. The fast editing of a Julien Temple documentary has no place here. There’s barely any old footage of Jamaica, let alone clips of the early Wailers, no matter how popular they were at the time. Even the earliest photo of Robert (everyone calls him ‘Robbie’) shows a fully formed adolescent. Forget about seeing any cute baby photos here. Bob Marley was born to a rural teenager exploited by a much older man and grew up in a dismal slum. Post-war America this was not (though the budding singer did wash ashore in Delaware in the Sixties, impressing local heads with his homegrown).

This makes Marley unusually dependent on storytellers, giving it an appropriately loping pace. You wouldn’t realise that Bunny Livingston is Marley’s stepbrother watching this, but he’s a great interviewee, both proud and unafraid to display vulnerability. The array of voices gives dignity to those who strived in a perfectly unequal and primitive recording industry. Studio One janitor and sometime vocalist Dudley Sibley, who shacked up with a young Marley on the premises, is particularly revealing of a distant era. Understandably, Macdonald is especially pleased to have captured his story.

Demystifying the sanctified is fraught with problems. In fact, the most exposed figure seen here is Haile Selassie himself, perplexed by the boisterous crowd welcoming him on a state visit to newly independent Jamaica. He looks less like a living god than a posh little man in a military uniform, a universal symbol of the planet’s ruling classes.

Throughout there’s an implication that Marley, son of a philandering member of the relative elite and a naïve country girl, represented three hundred years of one island’s cultural miscegenation rather tidily. Jamaica after all is a place where slaves included white Britons as well as Africans, and it had been colonised since Cromwell’s time. It’s a valid point. Young Robbie suffered for being mixed-race in an already divided society, which explains his attraction to the relaxed outcasts of Rastafarianism. Racially, musically, even linguistically ambiguous, Marley makes a perfect universal symbol. Macdonald’s documentary, though, never really gets close to explaining why Dead Bob has proved so much more potent than Live Bob. The tantalising possibility that backpacking cultural imperialists left their copies of Legend behind after gap-yearing across Africa and Asia, thus inspiring global Bob-love, remains ignored.