It’s 1978. The scene is a discotheque in a shopping mall. Flashing lights, bippety-boppety basslines, guys with big sideburns and even bigger shirt collars. Everybody’s dancing and having a good time. Except for one man. Huge, bald, and very angry, the music seems to have sent him into a psychotic rage. He clutches his ears and screams before thrashing out wildly at anyone near him.

Outside, on the mall’s main concourse, a political rally is in progress. People start streaming out of the disco, past the prospective voters. “There’s a bald man in there and he’s going bat shit!” screams one man as he rushes past. “Disco blue,” goes the vocal refrain in a song by The Humane Society for the Preservation of Good Music, “You’re making me blue all the time”.

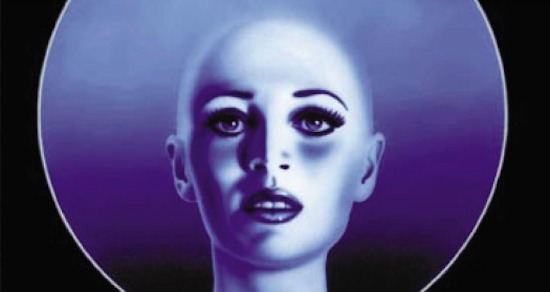

With its low production values and its rampaging jock, this could almost be a stand-alone short made by DJs Steve Dahl and Gerry Meier as part of their “Disco Sucks” campaign. But in fact it’s a scene from a very odd late 70s horror film called Blue Sunshine, directed by Jeff Lieberman. The story concerns a series of violent murders, each one committed by a different person who, up until that point, had seemed like a perfectly normal, upstanding member of the community – except for their occasional shortness of temper, their inexplicable headaches, and a strange tendency for their hair to fall out.

It transpires that all the killers were at Stanford together ten years earlier. And all of them had bought some ‘experimental’ strain of LSD called ‘Blue Sunshine’ from a guy called Edward Flemming (played by Mark Goddard) who is now running for congress. One man, a Cornell graduate named Jerry Zipkin (Zalman King), falsely accused of one of the crimes, is out to uncover the whole sordid affair.

Throughout the 70s, another Cornell graduate and former U.S. State Department employee called John D. Marks had been publishing a series of books highly critical of the CIA and its “cult of intelligence”. While Lieberman’s film was in production, Marks was turning reams of documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act into a best-selling book called The Search for the Manchurian Candidate about the CIA’s experiments using LSD.

Amongst the laboratories Marks exposed as complicit in the CIA’s top secret MK ULTRA project, was the psychology lab at Stanford. There it was that a young Ken Kesey, a student at the time, would volunteer and get his first taste of the drug that he would later spread across the USA in a multi-coloured bus marked FURTHUR. “No one could enter the world of psychedelics without first passing, unawares, through doors opened by the Agency," wrote Marks. "It would become a supreme irony that the CIA’s enormous search for weapons among drugs … would wind up helping to create the wandering uncontrollable minds of the counterculture.”

With shooting beginning before the book came out, it’s unlikely that Lieberman was aware of Marks’s revelations – and, anyway, he doesn’t push his story quite that far. In the end, the aspiring congressman Flemming is just another ex-hippie ex-dealer now gone straight and heading for the upper echelons of American society, like so many other baby boomers around that time. Still the film packs the eerie paranoid punch of early Cronenberg and mid-70s Pakula – even if, in this case, the conspiracy does not quite end up going “all the way to the top”. With its odd mix of political thriller and psychedelic horror, it’s hard for contemporary viewers of Blue Sunshine not to think of MK ULTRA, its accidental engineering of the psychedelic underground, and the bleak post-Altamont comedown from the first Summer of Love.

Blue Sunshine remains a curious cinematic monument to the death of the hippie dream. All the principal characters are of an age to have left college around ’68. The protagonist, Zipkin, is an outsider precisely because he’s the only one who hasn’t gone straight, cut his hair, and got a respectable job. But it’s hard to know whether, in Lieberman’s eyes, that makes him a hero or anti-hero. As Kim Newman puts it in his book Nightmare Movies, “Lieberman sums up the spirit of 1968 when he has one potential freak out confess that the break-up of the Beatles affected her more than the break-up of her marriage. The flower children have become the Living Dead.”

The scene in the disco was apparently frequently used as a projected backdrop when bands like The Ramones played at CBGBs. Steve Severin and Robert Smith later named their one-off duo record after the film. Severin, apparently, was qute the fan. This is not entirely surprising. The film has plenty to recommend it to lovers of strange music. In particular, a very interesting score – full of Xenakis-y string glissandi and creepy pitched percussion – by Charles Gross.

Gross would later work on some pretty big films (Turner & Hooch, Air America, etc.), but this was one of his first features. Back in the 50s, he had studied under Darius Milhaud at Mills College, at around the same time that Milhaud’s other pupils, Morton Subotnick and Ramon Sender, were starting their (pre-San Francisco Tape Music Center) ‘Sonics’ concerts series at Mills which would give works by Terry Riley and Pauline Oliveros their first performances. Milhaud had also taught Xenakis himself, a few years earlier in France.

Finally, Blue Sunshine can be seen as part of a trilogy of great mall films from the late 1970s. American suburbia had been re-shaped by shopping malls in the 1960s and 70s, their growth spurred by laws encouraging out-of-town developments like the accelerated depreciation laws of 1954 and, later, the possibility of commercial enterprises avoiding corporate income tax through banding together in Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs).

At the beginning of the 70s, Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock had regarded the rise of shopping centres with wide-eyed optimism for all the ‘choice’ they offered consumers. Despite the cautionary note of much of that book, he is positively ecstatic about California’s Newport Center. Visitors to the recently erected shopping plaza, he wrote, “cannot fail to be impressed by the attention paid by its designers to aesthetic and psychological factors. Tall white arches and columns outlined

against a blue sky, fountains, statues, carefully planned illumination, a pop art playground,

and an enormous Japanese wind-bell are all used to create a mood of casual elegance for the

shopper. It is not merely the affluence of the surroundings, but their programmed

pleasantness that makes shopping there a quite memorable experience. One can anticipate

fantastic variations and elaborations of the same principles in the planning of retail stores in

the future.”

But by 1978, certain cracks were beginning to appear in the veneer of this utopian gaze. Dawn of the Dead had made literal the trope of zombified mindless consumers staggering about an increasingly threatening mall to the twinkling percussion of Muzak. Two years earlier, the dystopian Logan’s Run had provocatively suggested that, in the future, everything will look like the Mall of America.

Blue Sunshine, likewise, spends its final act showdown in a mall. It’s the place where all the film’s themes come together. A shopping mall, the film seems to be saying, is a place uniquely inhospitable to someone in the throes of a really bad acid flashback.

A few years ago, there was talk in Variety and elsewhere of a remake. Original writer-director Jeff Lieberman was even onboard, talking up how well he believed the flim’s themes will “resonate” with “Millennials”. So far, nothing has coming to pass (and, frankly, it’s probably for the best). We can only guess, then, how this deeply, deeply strange film might have been re-imagined for an age in which the American mall is in terminal decline and the borderline between the real and the imaginary is under assault from forces far more pervasive than pills and blotting paper.