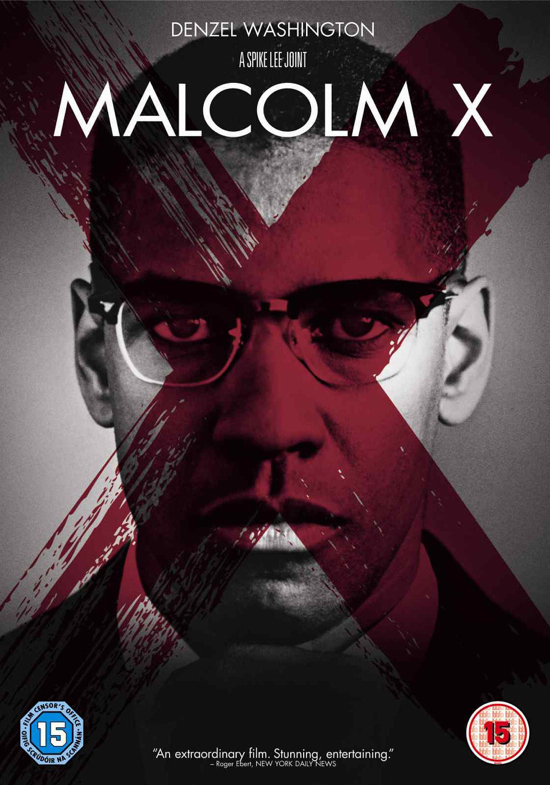

On its release in November 1992, the long-awaited biopic of Malcolm X topped out at number three in the US box office, right behind the sequel of a certain stranded little rich kid (this time in New York) and the peculiar misadventures of a vampire. It seems things in the film world haven’t advanced that much in those past twenty years – instead, studios seem merely to have consolidated these two concepts and produced, well, Twilight, as is my understanding.

But Spike Lee’s self-declared dream project was also a long time coming. Under the auspices of Marvin Worth, who had already produced an Oscar-nominated documentary on the subject back in 1972, the dramatisation went through years of rewrites, with stars ranging from Richard Pryor to Eddie Murphy attached at various stages. The production eventually settled on a version of the treatment originally penned by Arnold Perl, director of the aforementioned doc, and novelist James Baldwin. Both men had long since passed away by this point, and the latter’s family requested that his name be removed from the credits due to the extensive revisions (hence the final screenplay was credited to just Lee and Perl).

Lee campaigned hard for his chair as director and, after a protracted fight with distributors Warner Bros, ousted Norman Jewison (who helmed the classic 1967 racial drama In the Heat of the Night) on the grounds that an African-American director should be in charge of such a significant black figure’s biography. The feature went into production with a reduced budget, and came out the other end at a time of serious racial tensions.

So the story goes, executives at Warners had only just begun viewing Lee’s four-hour rough cut when the LA riots broke out in April 1992, unleashed by the acquittal of Rodney King’s videotaped police beaters. It is this videotape that intercuts the superlative opening credits of Malcolm X, with one of the title character’s more inflammatory speeches reproduced over the image of an American flag burning to leave behind, in almost superhero fashion, an X.

The first step in countering racism is to recognise it, and the movie opens in fine fashion during the war years in Boston, when a teenage Malcolm (Denzel Washington) still carried his preacher father’s surname Little. In a sweeping sepia shot we’re introduced to zoot suited Shorty (Lee) as he bops down the street towards a barbershop where Little will soon undergo his first ‘conking’: a humiliating ritual symbolic of the white man’s insipid domination, straightening hair by singeing the roots and scalp with a combination of egg, potato and lye. The sequence, a near-slapstick depiction, ends with Malcolm saying proudly, "Looks white, don’t it?"

From here we get in harsh tonal shifts a flashback of his earlier years, the "nightmare" that opens his 1965 autobiography, as told to Alex Haley, on which the script is based. In it we see the effect of his mother’s nervous breakdown and the attack on his Omaha home by Ku Klux Klansmen at a young age, cut into Malcolm’s loafing around and subsequent relationship with Laura (Theresa Randle) – a girl abandoned to become a prostitute and addict. "One of the shames I have carried for years is that I blame myself for all of this," he writes, as he leaves her in favour of a white woman, Sophia (Kate Vernon). Malcolm eventually makes it to Harlem where he finds employment, for a time, on the New York-Boston train line. He falls in with the wrong crowd, an apparent victim of the forced choices young black people face in the ghetto, though by his own admission he was always drawn to the rough side of the city. Malcolm then starts working for local gangster West Indian Archie (an outstanding Delroy Lindo), running numbers and doing coke, and finally lands himself in jail.

Thus ends the first hour of Malcolm Little’s tale and, judging by the excruciating length of some sequences (for example the dance hall number), this is meant to be the ‘entertainment’ portion, before the spiritual conversion. None of it is particularly entertaining though. Many of the scenes, over-played and near-farcical, are spliced with deep traumas, including the suspected murder of his dad. It’s an effect seemingly intended to jar the viewer, but it comes off as uncontrolled, undermined by Lee’s scattershot approach. The director seems too aware of his audience and, having been warned by such vocal figures as poet Amiri Baraka "not to mess up Malcolm’s life", he throws all of his style into a handful of set pieces. The remainder are noticeably restrained, even venturing into TV movie territory, with a melodramatic score to underline the emotion. Washington’s narration over much of this means we basically have an hour of exposition. There are however some directorial flourishes that do work, notably the periodic ominous gunshots. Sudden pistol fire resounding at choice intervals reminds the viewer of Malcolm’s inescapable fate.

The realisation of these gunshots becomes more lucid in the second half as the picture’s most intriguing elements come to the fore, during the activist’s self-education in prison and beyond, once his conversion to the Nation of Islam is complete. But it is as if Lee is saving all of the early provocative feeling from the Rodney King footage for the NOI phase, and that fire of the opening credits dissipates, smoking out any momentum. In prison Malcolm begins to convince himself of ideas he will hold for much of his life, notably a realisation of the black man’s position in white America. He copies out the dictionary and reads voraciously by his cell’s dim light, while the earlier sepia tones are leaked in favour of the grey scale of his lengthy incarceration. Malcolm’s learning of the cold reality of the streets prepares him for his role as spokesperson for the NOI and sidekick to Elijah Muhammad (Al Freeman, Jr). Once released he gives speeches spouting the racist segregationist views of Muhammad, all lovingly reproduced and heartfelt in delivery, while becoming a hate figure for the media, portrayed as the militant leader of a coming revolution. Malcolm, of course, later discovers that his leader has been impregnating young secretaries on the sly. When he exposes this truth he is forced out of the group, spelling his violent end at the hands of three shooters, which comes in a surprisingly shocking finale.

Amid widespread acclaim, a few critics were sensible enough to separate the man from the film and not get bogged down by the gravity of it all, recognising an extremely conventional and even by the numbers biography. In retrospect this seems very much to be the case, though if anything Malcolm X highlights the inherent problems in producing accurate biography, and not mere interpretation of select facts. The movie was always intended as a primer, according to Lee, a jumping-off point for audiences to discover more about Malcolm for themselves. Whether it achieves this goal is up for debate, with academics still arguing over the autobiography’s veracity in the light of newer works by Bruce Perry, detailing among other events Malcolm’s early homosexual encounters, and Manning Marable, who argues that "liberal Republican" Haley’s input skewed any chance of an honest portrayal of the man.

We get then, perhaps, an even more diluted portrait from Lee, with several heavy-handed editorial changes. Malcolm’s brothers Wilfred, Philbert and Reginald are excised from the picture entirely, replaced by the fictional character Bains (Albert Hall), despite Reginald being the man who first got his sibling involved in the NOI. Also missing is half-sister Ella, a larger-than-life woman who funded the pilgrimage to Mecca, in favour of a bolstered version of his wife Betty (Angela Bassett), who seems to play a minimal role in the autobiography (arguably telling of the NOI’s attitudes toward women). Alex Haley, the journalist assigned to ghostwriting said book, is himself conspicuously absent, despite the pair’s close relationship. Lee was also compelled to omit any references to Louis Farrakhan, after receiving "specific, direct threats" from the NOI leader.

Despite the final hour dealing with Malcolm’s exile from the organisation, little is done with the reels in terms of illustrating his perennial evolution. Malcolm’s slow awakening to his position is, as in the autobiography, frustratingly slow. It takes him until well into his thirties to admit that not all white men are devils. So it is unfortunate that so much of this biopic’s substance is devoted to his early and middle years, resulting in a sanded-down vision of Malcolm that smoothes over the rough parts (as did Haley, reportedly, in editing out his subject’s alleged anti-Semitism). It’s full of ideas X later retracted in favour of a more inclusive Pan-Africanism, and his view that only Islam can bring peace to America.

He travelled extensively during his last two years, to Mecca and around Africa. It was after these visits to the continent that he shifted his people’s concerns, crucially, from civil rights to human rights. Lee opts for a more closed and mythical approach, and though notable for its set pieces and recreation of some of the man’s more well-known speeches, the film seems to skim over the ideas relayed to his followers around 1964 and 1965, after his Hajj and before his assassination.

Context seems to be the key, in understanding both the book and the movie. Despite each of them being controversial in their own right, it is all-important that during Malcolm’s life race relations weren’t just a hot-button topic for political one-upmanship, but an issue that had real, murderous consequences. The film ends aptly in Soweto, with a cameo from Nelson Mandela. Though unwilling to repeat X’s famous phrase "by any means necessary", Mandela aids in the final message. On this note of anti-racism Lee completes his odyssey, albeit with less force than his hero Malcolm: a man who found his answer yet continued asking questions.