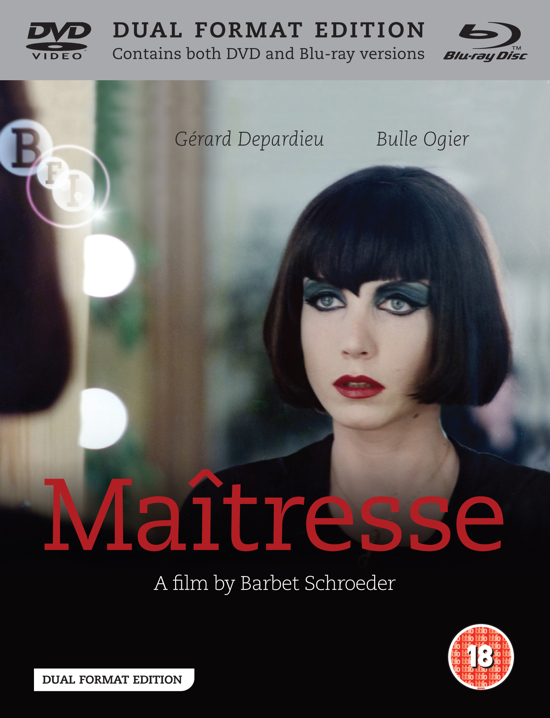

Barbet Schroeder’s drama Maîtresse has been released on Blu-ray and DVD to coincide with the BFI’s Uncut season, which marks the British Board of Film Classification’s centenary this year. The season attempts to chart the evolution of debates around censorship and explore how attitudes within the BBFC changed over the course of its existence. Maîtresse is an apposite addition.

The BBFC – back then, the C stood for Censors rather than Classification – had to reject the first submission of Maîtresse in 1976 under the Obscene Publications Acts (1959 and 1964). Then, in 1979, the Home Office’s Committee on Obscenity and Film Censorship (the Williams Committee) recommended fundamental changes in film censorship. The terms ‘indecent’ and ‘obscene’ needed to be retired, its report said, and material restricted on the basis of liability to cause harm, or having caused harm in its production. Essentially, this reappraisal allowed the BBFC to approve Maîtresse in 1981, albeit with nearly five minutes of cuts including the notorious unsimulated scene in which a woman nails a man’s genitals to a block of wood, and the harrowing (documentary) abattoir scene. It wasn’t until 2003 that the BBFC passed the film in its entirety.

These cuts are what make Maîtresse‘s place within the history of censorship in Britain interesting. This odd little picture was controversial precisely because it couldn’t be accused of being indecent or pornographic overall, but the censors’ first opinion, pre-Williams Committee, was that the scenes that were indecent were integral to the film and couldn’t be cut without damaging it. After 1979, Maîtresse was still considered liable to cause harm and to have caused harm in its production, but now it could be approved with those bits cut out. It could be argued that this approval was less respectful of the film and its audience than outright censorship, especially given the BBFC’s previous comments on the integrity of the film as a whole.

Maîtresse begins with petty criminal Olivier (Gérard Depardieu) arriving in Paris. He goes door-to-door looking for work and things to steal, claiming he wants to see what’s "behind people’s walls". It’s not long before he meets and falls for Ariane (Bulle Ogier), who also likes seeing inside people’s lives – but does so working as a dominatrix. By torchlight, Olivier discovers the basement where Ariane sees her clients.

The symbolism is generally, sleazily obvious: Ariane standing under a neon halo, or feeding insects to a Venus flytrap. The theatricality is specific; there are gloves, masks and strange shoes, props, curtains and mirrors. Ariane describes her work as creating ‘scenes’, visual recreations of fantasies – her own mises-en-scène. When they’re shown, Ariane’s authority actually looks quite difficult to accept – she’s clumsy with props, unconvincing with words – but her clients’ will to believe gets them past it, just as audiences see beyond shaky scenery and bad wigs.

Maîtresse is about what happens to this fragile balance after Olivier arrives. It explores the dynamics between Ariane and her clients in counterpoint to their romance. The movie plays with how the power between them shifts as their relationship develops, and it constantly challenges its own assumptions. For example, the connection between the couple’s shared voyeurism – which is not confined to the overtly sexual – and the performative aspects of sexual domination is one of its key concerns, and that tension is constantly rebalanced. Ariane has intellectual and financial power, and all Olivier has is masculinity, but he both accepts and pushes against these limits. He wants to do the driving, but follows her lead sexually. At one point, Olivier describes Ariane as an exhibitionist, but the difference between sex involving role-play in public with him and her performances for clients is profound. Their relationship is not one of dominance and submission, just informed by them.

Olivier’s young but questions nothing. He has no fear. Perhaps he’s not intelligent enough to be afraid. He’s thrown into what should be incredibly uncomfortable situations involving strangers and rules he’s not been told, yet Ariane trusts him to understand them. She doesn’t ask how he feels about her scenes till afterwards, assuming he was scared – so she wanted him to be, or wanted to pretend he was. Although he’s inexperienced, he takes it all in his stride. Is he performing too? Did she see a kindred spirit in him? The point is, it’s the opposite of how she treats her clients – in those relationships, negotiation and agreement of boundaries is fundamental. This is made clear when Olivier attempts to punish a client outside of the limits he’s agreed with Ariane. Something less cruel that hasn’t been agreed is less acceptable than something more painful that has. In creating scenes designed to assuage guilt with physical ‘punishment’, she’s kinder to her client than she is to Olivier.

Maîtresse shows us the things that are new to Olivier through his untutored eyes. It’s sympathetic, never judgemental of Ariane and her clients, but the thing about documenting fetish in this way is, it’s quite boring. What’s meant to be extreme – long shots, no cutting away to spare pain or embarrassment – becomes dull too easily. Maîtresse juxtaposes banal domesticity with long fetish scenes, but the sudden bursts of violence, rather than being shockingly effective, feel bland because they’re part of the same intellectual landscape as the domesticity. This constitutes a good point about sex in itself, and the way the film makes this point is probably the basis for the BBFC’s initial judgement that cuts would ruin it – but it also means watching the movie is a cold, detached experience despite its evidently abundant understanding of the kind of sex it portrays.

Luckily for the BFI, this release also coincides with the incredible popularity of Fifty Shades of Grey. That book’s apparently quite mild portrayal of BDSM has led to much debate about pornography in popular culture. It’s also been criticised for inaccurately portraying BDSM as a symptom of damage from traumatic childhoods. By contrast, Maîtresse is sensible and humane, even with hammer and nails. Ariane’s clients are normal people, their kinks – however ‘extreme’ – nothing to be ashamed of. For this reason alone, it’s a timely release.

Maîtresse is out now as a Dual Format Edition, containing both DVD and Blu-ray versions, and screens twice at BFI Southbank this weekend as part of the venue’s ongoing Uncut season.