Firstly I should say I’m disappointed in myself for not immediately registering this as a ‘nunsploitation’ film, despite being well aware of low-budget B-movie fandom culture’s love for the ‘-sploitation’ suffix, adapting it with gleeful promiscuity across a vast number of eyebrow-raising 1970s European cheapies. Maybe it was the surprisingly classy sun-dappled framing of Love Letters Of A Portuguese Nun’s‘ opening scene, where the virginal Maria plays at innocent courting rituals with her boyfriend in the leafy privacy of a forest. Surely director Jesus Franco’s reputation rests on more than just prolific sleaze, right? Given the time, the locations and a relatively steady hand behind the zoom lens, even he could turn in some respectable filmmaking once in a while… right? And yet within twenty minutes we have a sinful priest masturbating to loud orgasm in a confessional. Nunsploitation it is, then. We are, of course, very firmly in Franco-land throughout.

That’s not to say Love Letters isn’t a high point of his filmography, at least by traditional cinematic standards. It remains tonally consistent and thematically focused; it isn’t uneven in its pacing and doesn’t feel overly rushed in its production. Maria’s headlong fall into a milieu of sin, sex and Satanism is always underpinned by her sincere belief in God – the benevolent Christian version, who is supposed to look out for poor young girls like her, victimised by the corruption of Lucifer and the blind fervency of the Inquisition. Though the performance of Susan Hemingway as Maria is blankly unconvincing, we always return to her private moments of prayer, magnified by Franco’s trademark extreme close-ups, and this is the steady presence of a moral truth, even in the absence of God himself. When deliverance comes, it’s perfunctory and from a very secular source: an intervention by the local Portuguese prince, who makes no distinction between the Inquisition and the errant Satanic convent that’s been operating with impunity in its shadow.

Never the subtlest of filmmakers even among his low-budget peers, Love Letters is an outright condemnation of the Catholic church’s ongoing obsession with sexual sin, albeit one that quickly overextends into the realms of absurdity. In Franco’s view of history, the ideological dominance of Catholicism over its subjects, and the seclusion of its monasteries, covents and confessionals, creates the perfect environment for prurient cruelty to take hold. He was a voyeur with a hatred for authoritarianism, and this is as good an expression of those traits as one could reasonably expect.

Maria’s playful rebuff of her boyfriend’s advances is witnessed by the prowling Father Vicente, who wastes no time in shaming the girl, outing her as a hopeless sinner to her mother, and extorting the family’s savings from them before carting Maria off to a convent for a life of endless penance. That the convent turns out to be a secret Satanic sex cult is slightly more of a surprise. In other films, it’s Catholicism’s cycle of repression and guilt that drives people to evil, but here Father Vicente and the ‘High Priestess’ Alma have somehow done a full one-eighty into rampant Lucifer-worship. Franco wouldn’t dream of disguising his own arousal at all this, so what the hell, why not. Pasolini had abducted teens forced to eat their own shit by the heads of state, and the cinema cognoscenti had to stomach it. Love Letters is lurid but not exactly high camp all the way, and Franco makes the most of his beautiful locations by turning in a relatively tasteful film that buffers its more outrageous moments with simple, elegant photography.

It’s certainly true that the notably artful Euro-horror homages of today – from Cattet and Forzani’s giallo Amer (2009) to Peter Strickland’s brilliant The Duke Of Burgundy (2015) – reach back slightly further than 1977 for their most direct influences. Strickland in particular singled out several of Franco’s films from ’73 and ’74 for their drowsiness and wandering narratives. But these soporific qualities are absent from Love Letters, which shows little sign of psychedelic visual touches or the kind of loose-ended impressionistic storytelling popularised by the counter-cultural New Waves of the 60s.

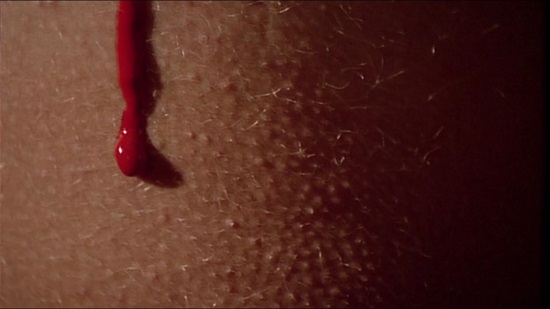

In a way, I rather miss all that stuff. There are a few scenes in sequence, when Maria first arrives at the convent, where the linearity seems to break suddenly down into psychosexual nightmare logic. But it’s only a brief indulgence, and Franco gets the film back on track after this terrifically entertaining diversion. The High Priestess is disturbed by her inability to bear Satan’s child, and Maria is next in line for this dubious privilege. It’s hard not to think of Rosemary’s Baby (1968) during the ensuing ritual, and neither Franco nor Polanski can entirely pull off the visual presence of the Antichrist in their respective scenes. Franco’s is of course cheaper and sillier, but with its rapturous editing – an overabundance of shocked/aroused observers clutching big wooden crosses to their naked breasts – it does at least achieve the balance of sleaze and ecstasy it clearly strives for.

By the time he made Love Letters, Franco was deep into a prolific spell of filmmaking that would last until the turn of the 1990s. In 1977 alone he made nine films, and this sits among an uncertain chronology of women-in-prison movies, some starring his long-time muse and enthusiastic partner Lina Romay. Most Franco fans (or advocates, we might call them) cite the early 70s work as his best output; not many will argue that anything after Love Letters is as intoxicatingly odd and memorable as Vampyros Lesbos (1970) or The Female Vampire, Romay’s 1973 screen debut. But there’s still a good chance this is his last ‘decent’ film, before the wave of low-budget Euro-exploitation broke into a torrid backwash of home video pornography throughout the 1980s.