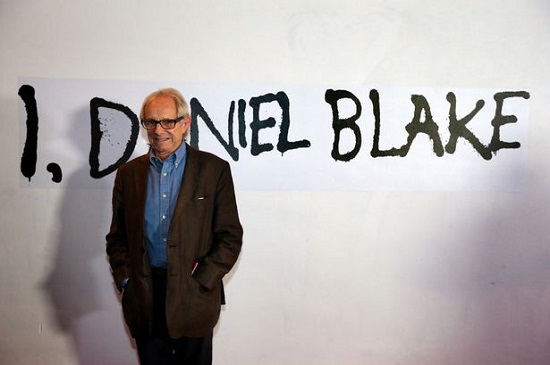

Fresh from his Outstanding British Film BAFTA win for I, Daniel Blake, Ken Loach tells me how troubled he is by the lack of working class voices at the ceremony. Typical of his quiet modesty, there is no mention of the film’s multiple successes or of the award itself, nor the second Palme d’Or of Loach’s career after The Wind That Shakes the Barley. Instead, he’s more interested in an issue that has been at the heart of his ground-breaking cinema for over fifty years.

“The people who presented the prizes, never mind the people who won, there were more presenters from Eton than any working class voices. You heard no working class voices amongst the presenters. Where were all the voices from the regions? I didn’t hear one. Where are the voices from the working class Londoners? I didn’t hear one. I mean, just think about the image they’re projecting. Why does every presenter have to be posh?”

For someone documenting social inequality since his direction of the 1966 BBC TV play, Cathy Come Home, it is perhaps unsurprising that Loach notices just how prominent the social injustices he’s been battling against all his working life still are in society. In his BAFTA acceptance speech, the importance of telling the truths about our society are just as crucial to him now as they were fifty years ago, and so too is calling the government to account for their dehumanising treatment of the poor in receipt of benefits.

“The most vulnerable and the poorest people are treated by this government with a callous brutality that is disgraceful…films can do many things; they can entertain, they can terrify, they can take us to worlds of the imagination, they can make us laugh, and they can tell us something about the real world we live in. And in that real world…it is getting darker, as we know.”

His acceptance speech chimed with many, not least the most poor and vulnerable who Loach portrays in I, Daniel Blake. The widowed Dan, a hard-working and skilful carpenter, is forced to claim benefits after suffering a heart attack. Still undergoing treatment, he is told he is unfit for work by his doctors and consultants and is ordered to rest. However, mirroring a situation thousands of people have found themselves in under the brutal new benefits system initiated by the former head of the Department for Work and Pensions, Iain Duncan Smith, Dan is deemed fit for work after undergoing an Atos health assessment by a “healthcare professional".

Dan is thrown into a Kafkaesque nightmare of bureaucracy featuring a lengthy and complex appeals process, degrading interviews and patronising CV workshops. Loach made the actor Dave Johns who plays Dan fill in a 52-page application for Income Support to help him empathise with the nightmarish system claimants are put through. His situation is also mirrored in that of Katie, a single mother given the run around as she is forced to move from London to Newcastle and claim Job Seekers Allowance. She faces tough sanctions in an inflexible system designed to punish rather than help those most in need of support.

I ask Loach how it feels to still be tackling issues of poverty, fifty years since Cathy Come Home highlighted the government’s failures on homelessness in the UK. “I think it’s not a surprise given the way politics has gone since the election of Margaret Thatcher really. It’s been one long process where the power of the big corporations and the power of big businesses is prioritised over the collective interest of the people. The economic system produces mass unemployment – it produces levels of poverty, of inequality, of people in precarious work where they can’t earn a living. And in order to justify that, people have to be told that the poverty is their own fault.”

For Loach, I, Daniel Blake was always about creating a truthful representation of poverty under the current Conservative government. The manager of the Tyne and Wear Jobcentre Plus so damningly criticised in the film, Steve McCall, recently argued that the film was not a true representation of people’s experiences, something echoed by Iain Duncan Smith shortly after the film’s original release. Loach, however, explains the painstaking research he and long term writing partner Paul Laverty carried out to ensure they captured the true reality of the many claimants.

“The research was done with PCS members who were job centre workers. The film is actually full of ex job centre workers. We said to them ‘anything you see that isn’t right – just tell us!’ so they contributed to it in a big way. We know it is accurate. There was someone last night in Coventry [Loach attended a free public screening of the film to raise awareness of the issues in the community] who was a PCS official and he said, ‘no question, of course it is accurate.’ People like Iain Duncan Smith, they’ve created [the system] – of course they’re going to say it’s not like this or that – they’re responsible.”

Both Laverty and Loach interviewed hundreds of people about their experiences for the film, but found a wall of secrecy when it came to involving the DWP itself. “The job centre workers weren’t officially allowed to speak to us. We weren’t even allowed to go into a job centre just to see the layout, just to observe it from a design point of view. You can go into a police station, you can have a policeman come to work in the film (as there was in the film), but job centre coaches were not allowed to speak to us, they weren’t allowed to be in the film or they’d face a dismissal. So the secrecy with which they operate is absolutely disgraceful.”

Like many of Loach’s films, I, Daniel Blake focusses on just a small number of characters to tell a much more complex story. Dan, Katie and China are the three central characters Loach uses to explore a process systematically failing hundreds of thousands in the UK. I wonder if it’s difficult to condense so many testimonials into just a handful of characters, but for Loach, finding the common threads of each helped to create a simple story with a powerful message.

“It was a mass of bureaucracy and a mass of regulation and hundreds of stories. That was what Paul Laverty did. We did a lot of research together and Paul did a lot more on his own and then out of that we talked about the characters we would like or that we thought would be important. Paul then wrote the two main characters and then he began to distil a very simple short story out of the many complexities of the situation.”

The poverty on display in I, Daniel Blake is much worse for Loach than that he saw in the 1960’s at the start of his filmmaking career. “We’ve got all this new technology, we should be able to share out the work, we should be able to share out the benefits of it, but in fact it is used to extract profit for a few and to impoverish the vast majority. So I think it’s not a surprise [that things are worse], but what is shocking is the public debate as it were, doesn’t point out this absurdity. We’ve had all this new technology, all these new inventions – we can feed everyone on the planet, we have the resources to live with all our problems solved, yet we’re locked into a system which cannot do that, which actually makes this worse, so there’s that paradox and that is the most shocking of all.”

“In the 1960’s,” he continues, “there was a sense that if there was a problem, people would work together for the common good. And that follows the 1945 settlement where we founded the National Health Service, money was put into council housing, there were good houses built, we owned the gas, the water, the electric, the coal mines and the steel industry. All that has been thrown away; Thatcher destroyed that and that’s why it’s much worse today.”

The fiercely socialist Loach supported Labour until the Blair-Brown years. Whilst he’s still no longer a member of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn represents a new hope for Loach in getting the party back to its socialist roots. Loach speaks regularly at Labour Party events and I, Daniel Blakeeven got a mention in the House of Commons when Corbyn challenged Teresa May to watch the film for a true understanding of the misery her party’s policies inflict on the poor.

Loach speaks candidly about his hopes for the Labour Party of the future. “The answer in the end has to be political,” Loach begins. “We’ve got to have a political party that will change it. And it needs a big social movement alongside the political party, but for me Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell, if they can stay in power and if we can get a huge movement behind them, then they will change it. If they lose, then I think we’re set back another 50 years because I can’t see anyone else doing it. I think it’s really critical… everyone will have criticisms of the Labour Party certainly and the Labour Party in the past I would oppose tooth and nail. They allowed sanctions and the work capability assessments so I’ve no, no support for the Blair-Brown government whatsoever. But I think Corbyn is facing the opposite direction. If we can keep him in power and if he could get elected in, I think things will change. But the biggest obstacle to that are all those Labour MP’s who do nothing by attack him. They’re the problem. They’ve got to go really if we’re going to win.”

Whilst his forthright views will no doubt annoy anti-Corbyn supporters, Loach’s unwavering belief in the socialist roots of the party come from a passionate and urgent desire to radically change the status quo of British Politics. Often considered his masterpiece, his direction of Kesarguably sought such a change back in 1969. Facing a life down the coal mines, the failure of the education system to help the working classes was brought into the consciousness of many through Billy Casper, in the same way Cathy Come Homebrought the issues of homelessness into the House of Commons and in increased donations to the then newly formed Shelter and Crisis charities.

Like Kes, I, Daniel Blake, looks at the inadequacies of the education system as the middle-aged Dan faces alienation from the “computer by default” rigidity of the DWP; Katie longs to get back to her books to escape the poverty she is in, her only hope being the Open University. With a government cutting adult education, closing libraries and introducing divisive grammar schools, the government’s refusal to allow self-improvement, according to Loach, seems to be a central theme to keeping archaic class orders firmly in place, an issue he still feels is relevant to his filmmaking.

“[Education] is a huge element. It’s a huge issue and they’re stripping out every vestige of civilised society. The shutting of libraries is just vandalism, cultural vandalism. Where I live, the library is being moved from a good central location where everyone can use it to some old council offices on the edge of the city. It’s going to be cut back, the number of books will be cut back…[The councils] see nothing but money. They see no value in what the public contribute and what we can collectively do culturally and educationally to live a good, civilised life. And everything they can raise money on, they will sell. It’s a huge struggle.”

Typically, Loach’s filmmaking contains actors from working class backgrounds. Actress Hayley Squires (Katie) and comedian Dave Johns (Daniel) have both spoken passionately about the need for increased representation of the working classes in cinema. With few British working class voices visible on screen, it’s something Loach feels the film industry must change.

“The people who pay for films can commission films that are representative of the people. Stories that represent the whole life that is going on, people’s daily lives – they can commission films like that. They commission far more about the Royal Family and the aristocracy then they do about the real lives of people which are much better stories frankly.” It’s something he sees entwined with the lack of working class voices at “showpiece occasions” like the BAFTA’s. “It’s not realising that the richness of language is in dialect. Apart from being snobbish, it’s anti-academic. I mean, history is contained in language, and in the formations of language, in the rhythms of language and the vowel sounds. It not only contains our history; it contains our humour. Try listening to a posh comic – he won’t make you laugh! The comedy is expressed through working class language.”

Despite its brutal and emotive realism, I, Daniel Blake has moments of humour where it’s mostly used as a device of solidarity to unite those struggling to cope under the weight of a system designed to crush. Yet the mood towards the end of the film darkens considerably as we see the system finally breaking its two central characters. According to official government figures, in the period following the introduction of the new, tougher benefits tests, over 2,380 people died shortly after being declared “fit for work” by the DWP. Increasingly seen as a national scandal, campaigners are fighting for Iain Duncan Smith and his department to face prosecution for the deaths. Of those who make it to appeal, over 60% are successful in having all their benefits reinstated, something further exposing the flaws in the already failing system.

For Loach, it was important to cover the issue. “Those cases were very much in our minds. I think it’s over 60% of cases when they go to appeal, the opponent is successful. There are worst cases – there are people who have been driven to suicide and there’s one very important case of Michael O’Sullivan in Camden. We met his daughter, Ann Marie, who is a terrifically brave young woman. They’ve established, in a Coroner’s Court, at the inquest into Michael’s death that the DWP were in part responsible for his suicide. This is a really critical judgement, and [the family] are demanding an apology and justice from the DWP and the DWP are ignoring them. The arrogance of that in the face of a legal judgement is just absolutely shocking.”

Loach is certain that Iain Duncan Smith should face prosecution for the deaths of those affected. “I don’t know whether it will happen – it certainly should. I mean that man should not be in public life. Leave aside the fact he’s so sanctimonious and self-righteous which turns your stomach when you look at him. Nevertheless, for the misery he has inflicted and is proud to have inflicted, he should. That’s what is so disgusting – he is proud of his work.”

One of the most emotive scenes in I, Daniel Blakeinvolves the food banks Loach talks of. When Katie visits a food bank after struggling to feed her family and herself, she takes to extreme measures when facing collapse from hunger. Loach again blames such instances squarely on Duncan Smith. “You go to food banks and you see people who are so desperate because they’ve got no money and they’ve got kids, and the anxiety and worry and the sheer hunger that man has imposed – he should be driven out of public life. The man is an absolute disgrace.”

Despite being an octogenarian, Loach is as politically active as ever, frequently speaking at Labour events and raising awareness about the political issues in I, Daniel Blake. Through the film’s distributor, Loach has even arranged for the film to be shown for free in community groups up and down the country. I ask him about retirement and he is typically coy on the subject. “I don’t know really [laughs]. We’ll have to see. I take each day as it comes.”

Loach is one of only a handful of artists challenging the treatment of the poor under the current government through cinema. Look closely and it’s hard to find the working classes. They’re not visible on the screen, at our awards ceremonies our even our televisions any more. Unless there are more like Loach, the real cultural vandalism will be the failure of the arts to support the communities who need our help now more than ever; the voices from the regions must be heard.

I, Daniel Blake is out on DVD and Blu Ray now