Since the late ‘70s Julien Temple has been documenting Britain on both the big and small screen. His debut film was The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle, which still remains controversial amongst punk rock fans. Temple somewhat rectified it with The Filth And The Fury which told the Pistols’ story through the band members instead of their manager Malcolm McLaren.

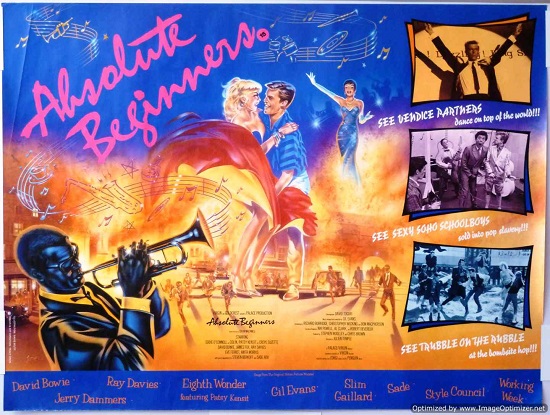

Throughout the ‘80s Temple made some of the most iconic music videos of the era for artists like Culture Club, David Bowie and Dexys Midnight Runners. However he had a itching to go a step further and direct a narrative feature film, which culminated in Absolute Beginners, an adaptation of Colin MacInnes ‘Mod bible’ of the same name.

The film is a technical marvel from the highly acclaimed opening tracking shot to the end. However it was blamed for the undoing of Goldcrest Films and was considered by the media to be a British Heaven’s Gate. Temple was forced to flee the UK to Hollywood so he could get work, but in more recent years he has returned to the UK and has made a strong succession of music documentaries. Absolute Beginners is also available on Blu-Ray for the first time from next week.

How do you feel about the Absolute Beginners Blu-Ray coming out after all these years?

Julien Temple: Yeah, it was circling Pluto for 30 years or 35 years, whatever it is, so it’s good to see it back in orbit. Yeah, I mean the whole thing is mixed emotions to me—it was kind of brutal baptism of fire in a lot of ways and I obviously didn’t get to finish editing it – we were kicked off of the shoot. So, you know, I do feel like it’s kind of a botched thing in some ways. I think there’s some fantastic things about this film, which is why it’s probably survived, but it was flawed in certain areas that I hold myself responsible for. Also the nature of the way we were treated didn’t help at the time, and I had to leave England after shooting it, because I couldn’t get any work here. I had to survive the kind of mental meltdown that goes with that kind of thing. So it’s mixed emotions. I’m proud that it looks good on Blu-Ray, because you spend a lot of time making it look good, but yeah – a cocktail of emotions

One of the things the film is known for is the great tracking shot at the beginning. What is your favourite cinematic tracking shot?

JT: I like Orson Welles’ shot in Touch of Evil, I like Martin Scorsese’s homage to Absolute Beginners in Goodfellas as well. I love a great tracking shot and I like Rope, which is a tracking shot for the whole film.

The film covers immigration, racial tension and a Mosely-inspired politician. Does Brexit passing bring up any thoughts about the events and attitudes depicted?

JT: It was analysing the beginning of the immigration process in the fifties, although immigrations is what this island is based on like every other place. But you know, in modern terms, immigration really hit London in the fifties, and the film has that in its course, so yeah, it is a film with a Brexit resonance. I was trying to make a socially, culturally responsive film in a Hollywood musical format because I thought it was the complete opposite of punk rock, but it is a social commentary as well as a song and dance piece.

I understand you and Jeremy Thomas have been working on a Kinks film for awhile. How is that coming along, and when can we hope to see it?

JT: Yeah, we’re getting that up and going actually. We’ve got a very good script, got the two main actors, now we just need the last bit of money.

I also understand that you have shot most of a film about the last few years of Marvin Gaye. What can you tell us about that project? Any news of whether it will come back to life?

JT: It went down in flames, or up in flames—the producers lied about money, so we shot for about five weeks and then they told us no one was going to get paid. Just another tale of the movie business, I guess!

I have read that you didn’t get to edit Absolute Beginners, and that you were later offered the chance to re-edit it. What led to your decision to leave it the way it is?

JT: Well, I had been asked to do that, but you know I’ve got a lot of things on, so I can’t do it at the moment. Maybe one day I’d do it. It was very difficult because the way it happened was that we got fired, and we were blamed for bringing down he film industry and stuff like that. When the shoot finished we were taken off it, the producers and myself, and they had three editors—one took the beginning one the middle and one the end and they cut the opening shot up into about a thousand pieces. They didn’t like the ambition of that, I guess, and they couldn’t make it work. So they said you’ve got two weeks over Christmas but you can’t reprint anything. So we spent most of the time trying to put that opening shot back together. We ran out of time to truly make the full impact on it, so that was one of the most difficult things to take at the time, partly because the other two films that Goldcrest had done together were probably twenty times more over budget than our film. I think we were very much blamed for the hype, which made it very difficult as well, because we were pretty young at the time. The movie industry was kind of like “if you want to make a film come back in 40 years, and start sweeping the floor and work your way up,” so we couldn’t get the money for it. We tried to get it in The Face and the NME and we created a kind of publicity blitz, which kind of snowballed out of control, so people were reviewing it before they’d seen it and there were national cartoons about how it was destroying the film industry. The whole thing was a very feverish atmosphere to be working in. Obviously, in other countries it didn’t have that backwash, so in France and Spain and America, it was much less seen through that lens of hype that surrounded it.

What were the biggest design challenges with creating the visual appearance of the film, such as the sets and musical numbers?

JR: Yeah, you know a musical is a complex thing. So there was a lot of pre-planning that went into the film. It took us a lot of time to get the money. We had a false start the year before, so I did have a whole extra year working on the visual side of it. The Soho set was a miraculous thing, and it was very sad when we had to pull that down. It really became a second home for all the Soho clubbers at the time, who were the extras, so they’d leave the clubs and come to the set, so it had this vibe of a club. It would have made an amazing night club actually! But yeah the sets were fantastic – the art direction on it and the camera work on it’s just great. It looks great in 70mm, that’s really how it should be seen.

I would love to see a 70mm print of it some time.

JT: Yeah, you can see all the camera cases at the back of the set in some of the shots in 70mm!

Do you have any regrets about not doing a more straightforward adaptation of the book?

JT: I’m certainly happy to live with the way I did it. I didn’t want to make a Ken Loach film.

How do you go about choosing subjects for your documentaries, and how many of them are commissions?

JT: Well, that’s hard to say… probably none of them are commissions, other than people asking me if I’m interested in something. It depends: a lot of them I want to do, sometimes people say something and it sounds interesting. You know, if I can get excited about it, I don’t mind whether I’ve thought of it or someone else has. It’s kind of great in some ways to do things you hadn’t necessarily expected you were going to do.

Of all the music videos you’ve done, which one is your personal favourite?

JT: Well I like “My Way” with Sid [Vicious]. I don’t know, I did a lot of them, and some are really bad and some are good. I don’t know, there are loads of them. I loved working with some of the people, so that’s a big part of whether I like it or not, in a way.

Do you have a Dennis Hopper story?

JT: I do…Well, I first met him [when I] was shooting a thing [‘Running Out Of Luck’] in Rio with Mick Jagger, for his ill-fated solo album. The idea was he’d gone to Rio to do a video or a long-form video and wanted to have a New York dance set built on some Rio stage, so we needed someone to play the video director. I just saw Dennis Hopper in the lobby of the Copacabana Hotel sitting there one day, and I thought, “Oh, he would be the perfect guy to do this.” So we approached him. He was there trying to dry out on drugs, which is a funny place to go and do it, but anyway, he said “yeah, sure.” So, you know, we shot with him. But by then he was not the Apocalypse Now Dennis Hopper. He was great to work with.

Do you have any thoughts about the 40th anniversary of punk?

JT: I was more interested in the 39th anniversary! I mean, it’s all a bit of a media circus and, you know, not really what it was about. Anything that keeps the underlying ideas of it alive is good. I think it’s wrong to make it into some kind of museum piece or collectors item. I found that funny, the guy saying I’m going to burn my £2.5 million collection of punk art; the idea that it’s worth such a fortune is such a bullshit notion in the first place. I’d say burn the notion before you burn the art! But I’m not that impressed by anniversaries really.

How do you feel about being at the stage of your career where your work starts being the subject of retrospectives?

JT: It’s a distraction from keeping going, in a way. I mean, in a way it helps you, I mean for many years… I guess I’m trying to make up for lost time because Absolute Beginners did impact on what I was able to do for about 25 years. I just want to get on and do some stuff, really.

What is your next film project?

JT: Well, I’m actually working round the clock at the moment to finish a film about Keith Richards, his childhood. It ends with the Stones beginning, and it’s going to go out on the 23rd of July. It’s called The Origin Of The Species. Interesting guy! He’s a hilarious and funny guy, whatever else he is.

Absolute Beginners is available on Blu Ray from the 25th of July