Sometimes it’s difficult to believe that we’re almost a quarter of the way through the 21st century. The relentless passage of time has likely been blowing people’s minds since they first started counting it, but there’s something about the progression of our current era that’s particularly hard to grasp. This could be partly due to the fact that we’ve already experienced several versions of this era before. Countless sci-fi films tried to envisage what life would be like in this new millennium, and while it was obvious that few of these predictions would turn out to be accurate, the ways in which reality diverged can still leave a feeling of emptiness, or missed opportunity. It often seems as though we’re living with the same forbidding mood and alienating social structures depicted in a lot of classic sci-fi cinema, only without space travel, cyborgs, or any other exciting parts that made it bearable to viewers.

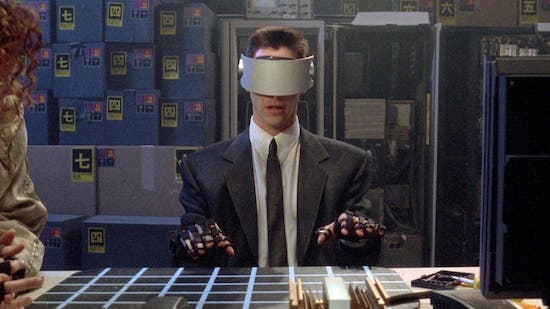

This year saw us catching up to the setting of an unfairly under-appreciated sci-fi movie, which was one of the most notorious commercial and critical flops of the 90s. Johnny Mnemonic has a strange, incoherent vision of the year 2021, and it completely failed to resonate with audiences in 1995. Despite this, it still draws more than enough eerie parallels to our own version of dystopia. It’s also a fascinating time capsule, from a relatively recent period that also feels impossibly remote.

The film was based on a 1981 short story of the same name by William Gibson, the influential sci-fi author who is credited with inventing the “cyberpunk” subgenre. Its titular character is a courier who allows corporations to keep their most sensitive data safe, by transporting it in a special storage device implanted inside his head. Offered a huge fee to carry a new bundle of data exceeding even his enhanced memory capacity, Johnny takes on the job in the knowledge that he could suffer permanent psychological damage if he doesn’t offload it on time. He’s soon caught up in a conflict between the powerful corporate world and an underclass that has been devastated by the effects of NAS (Nerve Attenuation Syndrome), a global pandemic caused by over-exposure to technology.

Though this scenario might seem a little ridiculous today, Gibson was one of the first writers to see the extent to which various emerging developments – data processing, artificial intelligence, and particularly the internet – could completely reshape our world. He was particularly interested in how they could be used as a form of control, and how they might also be taken out of the hands of authorities and reappropriated by people living on the fringes of society. With a sixth sense for how things were likely to play out in the years to come, he also coined the term “cyberspace”, in another short story in 1982. This was a few months before internet technology was first standardised, and a full decade before it made its way into the popular consciousness in the form of email and the world wide web. Though Gibson intended his phrase as nothing more than a meaningless commercial buzzword, we’ve now fully accepted the idea that the rapid transfer of digital information has created a kind of virtual “space”, which is somehow separate from the physical world.

By the time Johnny Mnemonic made its way from page to screen, it was becoming clear that the internet would have a central role to play in the future of society – though the details of how it would work were still a little hazy. 1995 saw the release of two other films also trying to dramatise the new information superhighway, for a moviegoing public now enjoying what Microsoft’s Windows 95 software had to offer, but perhaps not yet familiar with the gurgles and bleeps of a dial-up modem. The Net was a taut thriller starring Sandra Bullock as a prototypical Extremely Online woman, whose identity is erased as part of a shady government conspiracy. Meanwhile, Hackers starred Angelina Jolie and her soon-to-be husband Johnny Lee Miller as gifted high-schoolers who use their web surfing skills to disrupt global markets and extort a number of major corporations.The figure of the “hacker”, and the cyberpunk genre more broadly, would reach its cinematic zenith four years later with 1999’s The Matrix. The Wachowskis’ hugely popular martial arts/sci-fi hybrid closed out the decade, and ushered in a new century, with the oddly plausible idea that there might not be much reality left outside the computer.

Johnny Mnemonic has aged less gracefully than The Matrix, but it still has all the makings of a cult classic. It also stars Keanu Reeves, doing a kind of dress rehearsal for what would be his most iconic role. Surrounding the film’s bonafide star, who was hot off the success of Speed at the time, are some entertaining and intriguing figures. The main antagonist, a Yakuza boss named Takahashi, is played by Takeshi “Beat” Kitano, a Japanese former stand-up comedian and game show host. Starting at the end of the 1980s, Kitano had made an impressive pivot to directing and acting in a number of idiosyncratic gangster films. He’s sadly underused in Johnny Mnemonic, but an arthouse/Hollywood, East/West encounter between him and Reeves is satisfying, and he manages to infuse his scenes with the deadpan menace that became his trademark. Teutonic B-movie mainstay Dolph Lungdren is also along for the ride, as a psychotic hitman who styles himself as a street preacher, and early hip-hop star Ice-T plays the defiantly “low-tech” rebel leader J-Bone. A rebel scientist, Spider, is played by former Black Flag frontman Henry Rollins, whose anti-establishment hardcore punk credentials go some way towards compensating his lack of acting chops.

The project’s worlds-colliding vibe is demonstrated most clearly by its director. Robert Longo was a visual artist who first came to prominence in the late 1970s, and who went on to shoot music videos for the likes of R.E.M and New Order in the 1980s. One of his most recognisable early works is a black-and-white drawing that was used by experimental guitarist Glenn Branca as the cover for his album The Ascension. (Incidentally, Branca’s downtown NYC collaborators Sonic Youth had paid homage to William Gibson’s fiction on their seminal 1988 album Daydream Nation, attesting to the popularity of the author’s ideas and subversive style amongst avant-garde tastemakers). Longo had been planning to adapt one of Gibson’s stories for many years, and the pair initially intended Johnny Mnemonic as a low-budget arthouse film. However, they were unable to secure funding unless they upped the stakes considerably. Working with Gibson’s own screenplay, Longo signed on to make a wide-release, $30 million blockbuster, for the first and last time in his career.

His film might not have much in the way of character development or narrative tension, but Longo’s neo-expressionist fine art pedigree is clear throughout. He uses all kinds of off-kilter angles and atmospheric lighting to create a strange noir atmosphere, as well as effectively realising some of the source text’s most indelible imagery. The rebels’ ramshackle base, Heaven, is a particular feast for the eyes, with its monolithic tower of salvaged mid-90s TV screens, and a glowing green water tank housing a code-cracking dolphin.

Ironically, the most appealing parts of the film are what cause it to fail as an effort to see into the future. What gave Gibson much of his counter-cultural clout was his rejection of the cold sterility of Star Trek, 2001: A Space Odyssey and other sci-fi classics – although this was a lot closer to how things would turn out in reality. He always liked his dystopias organic, dynamic, and grimy, and the satisfyingly tactile production design that Longo uses for Johnny Mnemonic stays faithful to this aesthetic. Even the internet is presented as a messy, vibrant thing, visualised as a 3D virtual reality world where a clunky animated Johnny avatar navigates fields of pulsating colour and solves abstract picture puzzles.

In fairness, Johnny Mnemonic was arriving just as the first wave of internet-mania was starting to crest, and very few people could have predicted how incredibly ordinary the takeover of this technology would become. Maybe it says more about our current way of living, and how deeply embedded we are in “cyberspace”, that we can no longer see it as something alien. Instead of being an imposition we’re forced to deal with, the internet has continuously met us more than halfway, subtly coaxing most of our routine activities online with promises of comfort and convenience. In doing so, it has exerted more control than any artist, filmmaker, or sci-fi author could possibly have imagined. And it’s our imaginations themselves that have been the most deeply affected by it.

What happens when the future we’ve all been dreaming of turns out to be so disappointingly mundane? Is it forcing us to live in our own fictional versions of reality? Towards the end of Johnny Mnemonic, J-Bone hijacks the airwaves to share a decrypted code that could provide the cure to NAS, the rampant neurological disease also referred to as “the black shakes”. Megacorporations have apparently been keeping this cure a secret from the world, as it’s been much more profitable for them to simply treat the symptoms. It’s not difficult to read this as a critique of mass media, capitalism, and particularly the corrupt private healthcare system in the US, although this war of information could now be interpreted in a number of other ways. Many people are rejecting the official narrative surrounding our own global pandemic, but in doing so they’re also refusing a vaccine that is freely offered, and sometimes even denying the existence of the disease altogether. The cyberpunk gesture of rebellion against the powers that be is becoming much less straightforward, as people are no longer able to agree on where the power lies.

There’s another famous Gibson aphorism that neatly sums up this situation: “The future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed”. As global inequality grows and the social fabric continues to fray, much of the population seems to feel outpaced by reality. And without the possibility of imagining a better world to come, different groups have been enabled by the growth of the internet to interpret the present however they see fit. Cinema is also giving up on forecasting what’s to come, relying on an endless cycle of safe reboots and reimaginings of the past, while algorithms increasingly divide audiences into their specific niches. Watching Johnny Mnemonic in 2021 offers a nostalgic reminder of a time when it was fun to guess what “our” future might be like, even if it was pretty far off the mark. Maybe futuristic sci-fi was never intended as a prophecy or a warning. Rather, it was something that encouraged individuals to see themselves as a collective, with a shared fate.

The Matrix Resurrections is released in cinemas on December 22