When I first became aware of John Fahey around 7 years ago, through his connections with esoteric NYC underground improvisers the No Neck Blues Band, I had no idea that instrumental steel-string acoustic guitar music minus vocal accompaniment was something I needed in my life. Yet when I first heard the eerily beautiful, mournful notes of ‘When the Springtime Comes Again’, I was instantly struck, as if by lightning, by the singular originality of Fahey’s sound, which seemed to call forth emotions in me that only the likes of Bartok had previously evoked. Then a year later in December 2006, at the Thurston Moore curated All Tomorrow’s Parties, my friends and I were preparing to leave our chalet in order to catch The Melvins’ second performance, when Fahey’s 1978 Rockpalast performance came on the TV. We all sat down again and watched him instead. As much as we all liked The Melvins, they’re no John Fahey.

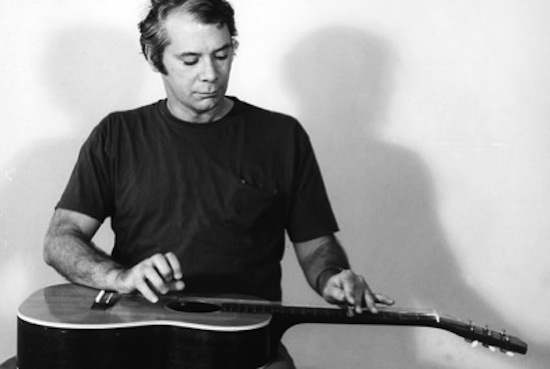

James Cullingham’s wonderful, expressionist documentary In Search of Blind Joe Death – The Saga of John Fahey, admirably portrays the many facets of the man behind the music and the myth. Fahey was a musicologist, folklorist (with a Masters from the University of California, where he wrote a study of blues guitarist Charlie Patton,) writer, independent record label boss, painter and prankster philosopher as well as a guitarist. A true American original of the stature of Sun Ra, Charles Ives or Harry Partch, Fahey existed in his own self-created universe with its own designated deity, which he called the Great Koonaklaster. Cullingham’s documentary beautifully evokes the landscapes which influenced Fahey in his formative years: fast-running river water and russet autumn trees, railroad tracks and trains in motion, box-turtles – the totem animals of the Great K. It also utilises collages of Fahey’s illustrations to lyrical effect.

A quote from Fahey’s first collection of stories, How Bluegrass Music Destroyed My Life, sets the tone for what is to follow: "There is something about guitars – maybe something magical – when played right – which evokes past, mysterious, barely conscious sentiments, both individual and universal. The road to the unconscious past. Guitar is a caller. It brings forth emotions you didn’t know you had." Reading Fahey’s writing, apparently saved from the garbage and coerced into print by the interest of his friend Jim O’Rourke, reveals how much of an original thinker Fahey truly was, even from his early eccentric childhood onwards.

Pete Townsend is one of several musicians who acknowledge the effect that Fahey had upon them. He explains how, upon first hearing Fahey’s unorthodox tunings, he thought "how is he doing that?" and adds: "He seemed to me to be the kind of folk guitar playing equivalent of William Burroughs or Bukowski." Members of The Decemberists and Calexico also appear to express their admiration, whilst Keith Connolly of the No Necks graciously debunks the notion that Fahey in later life was burnt out and difficult to deal with, saying: "he was doing exactly what he thought he should be doing, with the kind of presentation that he thought the time called for." Sadly, known Fahey associates Thurston Moore and Jim O’Rourke are absent from the documentary, which amounts to my only criticism of the film. Presumably they would have appeared, had their own personal schedules allowed it.

For its relatively short running-time of 57 minutes, the film covers the whole run of Fahey’s career. From the formation of Takoma records in 1959 – a necessity in terms of getting his own material released, which became an icon of independent record labels – through his adventures collecting old blues 78s in the black sections of the cities in the deep south and his rediscovery of artists like Skip James and Booker White, to his later, gratifying acceptance by a whole new generation of artists like Thurston Moore. Fahey plays the ‘gentlemanly outlaw’ throughout and although his later disintegration, due largely to the recollected pain of childhood abuse and self-medication through alcohol and chloral hydrate sleeping tablets, is apparent, it only serves to endear us all the more to the man. The mystique that built around the erratic behaviour of his later years, both on and offstage, is as essential a part of the ‘rock and roll myth’ as any stories told about certain electric guitarists of lesser artistic merit. Although the later clips of Fahey’s playing increase in increments of sadness, he is clearly still capable of producing music of great beauty. In this sense, his self-destructiveness is a further expression of the kind of iconoclastic and irreverent bearing best typified by his appearance on a 1970s guitar playing show, included in the documentary, where he casually flicks the ash from his cigarette into the sound hole of his recumbent Hawaiian guitar. Although such ‘punk rock’ asides as this add a delightful depth to the documentary’s depiction of the man, it is Fahey’s timeless music that constantly shines through. Anyone who is unfamiliar with his music should immediately seek out tracks such as the wonderfully titled ‘The Approaching of the Disco Void’, from the Live in Tasmania album or the gorgeous ‘When the Catfish is in Bloom’, preferably from The Great Santa Barbara Oil Slick. The latter track is so utterly evocative of the rural American landscape that you can almost see the wheels spinning on the wagons of the early settlers, almost hear the wind rustling through endless cornfields.

In Search of Blind Joe Death – The Saga of John Fahey is to be screened in coming months at Festivals in Belfast, Buenos Aires, Chicago, Madrid and Perth, Australia. It will be shown on BBC Four later this year and will also appear on DVD via Tamarack Productions.