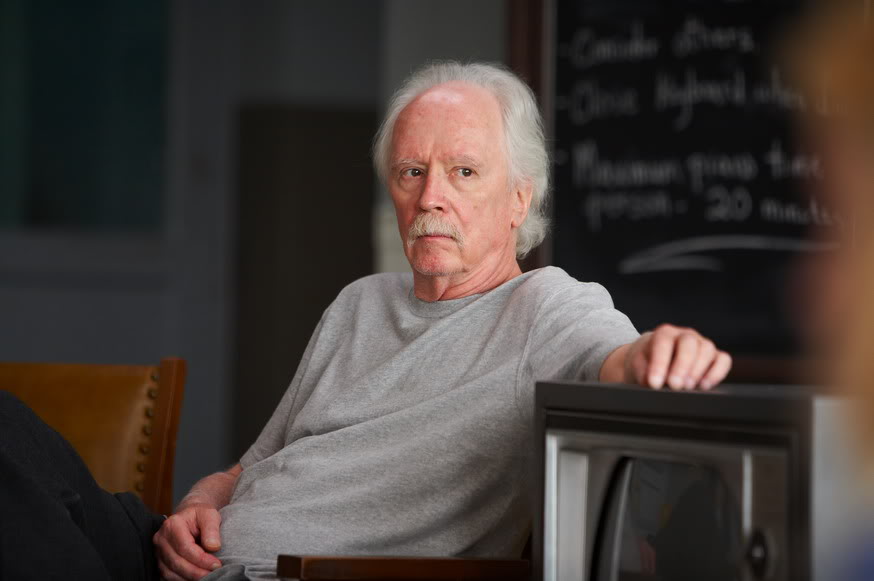

In the world of horror and sci-fi cinema, few figures carry the prestige and cult status of John Carpenter. A proper cinematographic Renaissance man, Carpenter has been writing, producing, editing and directing films since his 1974 debut Dark Star. In 1978, he rocketed to global fame with the classic horror Halloween, which birthed the slasher genre whilst also setting the bar so high that none of the following copycats such as Friday The 13th could ever equal it. One of the highest-grossing films ever made, Halloween not only launched an indefatigable franchise (and one of the genre’s defining bad guys, Michael Myers), but it also featured a timeless score, composed and recorded by Carpenter himself. He has even appeared in numerous films as an actor.

After the huge success of Halloween, Carpenter would go on to direct classic sci-fi masterwork Escape From New York; the critically-lauded, but commercially unsuccessful, remake of horror/sci-fi classic The Thing; Stephen King adaptation Christine; the oddball comedy Big Trouble In Little China; such cult gems as Prince of Darkness, They Live and In The Mouth Of Madness; and more recent B-movie explorations like Vampires and Ghosts Of Mars.

With the exception of The Thing, each one featured an instantly-recognisable soundtrack composed by Carpenter himself.

If John Carpenter’s legendary status as a film director is indisputable, he has in recent years become cited as a major inspiration as a composer, with the current synth and noise underground, from Wolf Eyes alumni Nate Young (notably in Demons) and Mike Connelly to the likes of Hive Mind, Sun Araw and Oneohtrix Point Never, often referring to his scores in their own sonic explorations. Dark atmospheres, haunted effects and subtle drone textures have long been a staple of Carpenter’s musical oeuvre, and the magpie-like tendency of many modern synth wielders, in particular, was always bound to turn to him as they looked to create their own sonic landscapes.

It was in this capacity as a pioneering composer, particularly with synthesizers, that The Quietus spoke to John Carpenter about music and films.

First of all, can you tell us a little bit about how you got into making music? Your history as a groundbreaking filmmaker is well known, but what drew you to making music as well?

John Carpenter: I grew up with music. My father was a world class violinist, a college professor, composer and a session musician for recordings in Nashville, Tennessee. He tried to teach me the violin when I was eight. I had no talent. Then he pushed me into piano. I had middlebrow chops. Then I picked up the guitar when The Beatles crashed through in ’64. I was drawn to their music, and to that of The Rolling Stones, Procol Harum, The Supremes and The Doors. From there, I went to the bass guitar. A small local Bowling Green, Kentucky, rock & roll band followed. We were called Kaleidoscope, but never made any recordings.

What made you decide to start composing your own film scores? Was it out of financial necessity, or because you felt you could capture the atmosphere of your films better than someone else?

JC: I composed the score for my first film Dark Star because I was cheap and fast. I talked to a couple of other composers but they all seemed weird. One guy had glitter all over him. Not that wearing glitter is a bad thing… it just didn’t inspire confidence.

How do you set about creating a score for your films? Do you start with the visuals and then extrapolate the music from what you’ve shot, or is the process of making music for your films symbiotic with the shooting and editing of your films?

JC: For me scoring is all improvisational. After the movie is cut, I synch my synthesizer to the cut footage and just start playing. Mostly I play all the parts. Sometimes I get a line based on a sound I hear driving to work. Sometimes the tempo of the temp music track inspires me.

Can you explain what your equipment was when you started out, and how it has evolved over time?

JC: God, I don’t remember what gear I used in the beginning. For Assault On Precinct 13 and Halloween I worked with Dan Wyman. He taught synthesizers at USC and used old tube synths. He had to tune each one before I could play.

A lot of your earlier films were defined by their emphasis on electronic instruments. Can you tell us what drew you to electronic music?

JC: Simple. I could sound big and powerful and I could play all the parts.

How long does it usually take you to compose and record a film score?

JC: It usually takes me a month or two these days to record a score. The score for Assault On Precinct 13 was finished in one day. Halloween took three days.

What do you think electronic instruments brought to your films, in terms of atmosphere?

JC: There’s something about synthesizer sounds that drives and underlines certain moods and tempos. When the electric guitar was invented suddenly there was rock & roll. Check out the scores for The Exorcist and Sorcerer from the 1970s. They still sound modern.

A lot of people think your film scores sound "simple", in terms of composition, but the theme for Halloween, for example, is in 5/4 time, so far from it! Did you have full reign to experiment with your scores? How did you integrate such explorations with the need to emphasis the dramatic nature of a film score?

JC: Most of my scores are simple. I would differ with this assessment on Big Trouble In Little China and In The Mouth Of Madness which I think demonstrate more complexity. The secret of scoring music for movies is to unify images, movement and sounds. And, yes, I have full reign to explore…

How do you feel about the fact that the Halloween score has become one of the most recognisable in film history?

JC: I didn’t expect it, but I feel great about it.

I’ve heard that they’ve now invented light sensitive novelty devices for halloween, where the movement of people in front of the device causes it to play the theme from Halloween. Somehow, that manages to be both amusing and scary. Where do you think the horror element of the score comes from? It obviously doesn’t follow the Hammer style of horror music. In the same way that your films often suggest horror as much as they show it, how do you think a film score can be used to suggest horror rather than overtly demonstrate it?

JC: First of all, I loved the Hammer scores of James Bernard, one of my musical heroes. His Quatermass and X: The Unknown scores are the greatest. His secret? He used to sing the title of the movie and that became the main melodic line. [His theme for 1958’s The Horror Of Dracula is derived from the rhythm of shouting, ‘Dra-cu-laaaaaa!’, Ed] The horror (scary) element in movie scoring comes from mood over complexity. Also from silence.

When it came to electronic music, were you aware of other electronic musicians, especially those involved in film scores, such as Giorgio Moroder or Vangelis? What sort of interaction did you have with those guys?

JC: I was aware of electronic musicians but had no interaction with them. Maybe I was scarred by the glitter-covered musician I met earlier.

The score for Escape From New York appears to draw inspiration from the music of Debussy. Can you describe the importance of classical music in the way you approach your film scores?

JC: There is actually a Debussy composition (‘Engulfed Cathedral’) used in Escape From New York. It is credited in the end title roll. For some reason a few disgruntled folk claim that I stole it without attribution. I consider this a crime against humanity. Todd Ramsay, the editor on Escape From New York, used ‘Engulfed Cathedral’ on the temp track. It worked well with the scene.

Horror cinema has long been characterised by its music, from Bernard Hermann’s theme to Psycho to John Williams’ iconic Jaws score, via the murky sound effects on The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Exorcist‘s use of Tubular Bells. How do you feel your own scores fit in that canon, and were you inspired by how other composers worked on film scores before composing the music to Halloween?

JC: I was hugely influenced by Bernard Hermann. His science fiction/horror scores were simple and welded to the images. Also Dimitri Tiompkin. His score for the original The Thing was fabulous.

The music on The Thing was notable in that you brought in Ennio Morricone to do the score, rather than do it yourself, yet at the same time he seemed to borrow much from what you had done on earlier films. Was his presence a studio imposition, or did you want to leave one part of the creative process to someone else for a change?

JC: I got to work with Ennio Morricone! His film scores are seminal. My God, who wouldn’t want to work with him? Ennio was a kind man, a gentleman, very wise and talented. He was a dream to work with.

Since the mid-eighties, you seem to have changed your approach, musically, shifting away from electronics towards a more prominent use of guitars. Can you take us through the thought process behind this change?

JC: I used guitars on Vampires and Ghosts Of Mars (there are a couple guitar lines in Escape From L.A. and In The Mouth Of Madness). I don’t really see it as a major change in that most of my work was still done with synths. On Ghosts Of Mars I used Joe Bishara as a sound designer on some of my stuff. He brought an electronic depth to my stuff.

Do you think you will return to a greater emphasis on electronics in the future?

JC: As I said, I never left electronics in the first place!

Your scores have been cited by a lot of modern synth/ noise/ underground bands as a huge influence. Are you aware of this? What do you think of the resurgence in interest in your scores, as well as those of Goblin or Vangelis? Is it a case of people catching on belatedly to the innovations you spear-headed?

JC: I’m flattered by this. But there are also tribute bands to the scores from Sonic the Hedgehog and Mega Man video games so I try to keep this stuff in perspective

In the early days, you were pretty much the sole driving force behind the music of your films, but recently you’ve been known to collaborate with guys like Jim Lang. What was the creative decision behind these collaborations?

JC: I’ve had many collaborations: Dan Wyman, Alan Howarth, Jim Lang, Dave Davies, Shirley Walker, Bruce Robb. I need help.

A number of your films have been remade recently, from Halloween to your remake of The Thing, via The Fog. How much involvement do you have with these projects? Do you think the current Hollywood emphasis on remakes betrays a lack of invention? Do you think it would be possible for a maverick such as yourself to make a name for yourself today in the way you did back in the seventies?

JC: The movie business has changed so much since I got in and I’m glad I got in when I did. But Hollywood has always remade and recycled older movies. The cost of making movies has risen tremendously. Studios look for what is closest to a sure thing.

Finally, what are your projects for the future? Can we expect a new John Carpenter film – and score – to hit our screens in the not-too-distant future?

JC: Future projects? A couple scripts in development (writing, raising money). Weekly jams with my son on my Logic Pro setup. Lots of NBA basketball watching. Enjoying this fabulous life that happened to me.