According to a recent profile in The Guardian, China’s newly named leader Xi Jinping is something of a fan of filmmaker Jia Zhangke. The claims relate to a 2007 conversation between Xi and the then US Ambassador to China, Clark T. Randt, Jr., in which the future President declared his love of Hollywood war movies and praised the awards success of Chinese films abroad. That year Ruby Yang’s The Blood of Yingzhou District had picked up the Oscar for Best Documentary Short Subject, while Jia’s fifth feature, Still Life (2006), had earned itself the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. Referring to the latter’s work as "very good" (as well as endorsing its "low cost"), Xi opened up an irony that has since been pounced on: how do you square this acclaim for Jia when his cinema has always cast a less than favourable eye on the country you will one day run?

Jia is arguably the most visible of the auteurs who make up China’s ‘Sixth Generation’. They first emerged from the film schools during the 1990s and set about re-inventing their national cinema in a distinctly different image to that which had come before. The ‘Fifth Generation’ was typified by Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige, directors who favoured visual opulence and gorgeous cinematography (as the titles made so immediately plain: Yellow Earth, Red Sorghum, Raise the Red Lantern). Rising to international prominence during the eighties – which led, in 1993, to Chen’s Farewell My Concubine becoming the first (and to date only) Chinese production to have won the Palme d’Or – they’ve subsequently been swallowed by the mainstream. Both have tried their hands at big-budgeted wuxia epics (Zhang finding the greater success in the early 2000s with Hero and House of Flying Daggers) and Zhang famously mounted the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics. Most recently, Chen’s latest feature, Caught in the Web, has been selected as China’s official entry for next year’s Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards, demonstrating the continued good favour.

By way of contrast, the ‘Sixth Generation’ have tended towards a far rougher approach. Their efforts have been largely governed by a documentary aesthetic and oftentimes made outside of the state system, thereby precluding any kind of official release. Consequently the budgets are mostly negligible unless outside funding can be found, although this has also meant that more sensitive subject matters can be addressed. Zhang Yuan’s East Palace, West Palace (1996), for example, was able to deal honestly with themes of homosexuality and police brutality. Wang Xiaoshuai, one of Zhang’s fellow students at the Beijing Film Academy, positioned his 1993 feature debut The Days, as a direct reaction to the "unnatural and pretentious" cinema of Chen and Zhang Yimou. Shot in black-and-white and only at weekends (so as to accommodate its non-professional cast and crew), this intimate tale of a slowly disintegrating marriage earned its director the attention of the authorities but for all the wrong reasons. He was blacklisted (alongside Zhang Yuan and four others of the ‘Sixth Generation’) for illegal filmmaking and yet somehow managed to continue working. 2001’s Beijing Bicycle was particularly noteworthy given its explicit nod to the Italian neo-realist classic Bicycle Thieves and all of the cinematic and political concerns that entails. If international audiences had yet to twig the impetus behind the ‘Sixth Generation’, here was an obvious indicator.

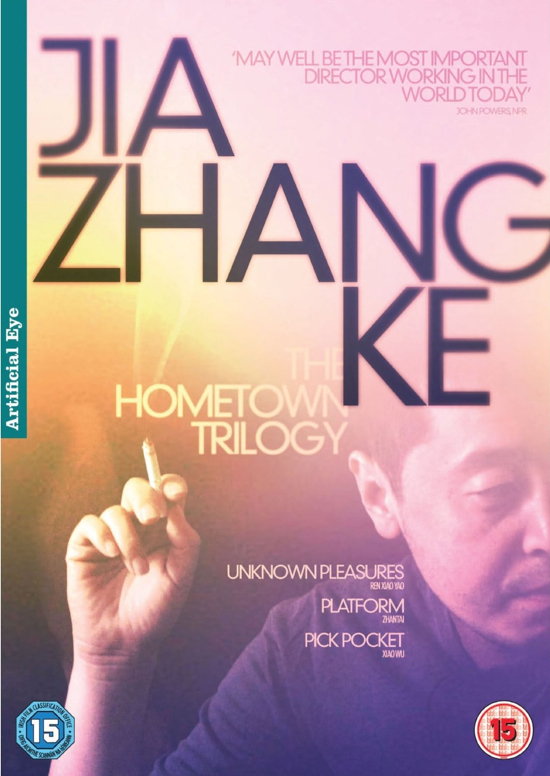

A few years younger than Zhang and Wang, Jia graduated from the Film Academy in 1997. His student efforts immediately marked him out as a defiant talent: the first, a ten-minute documentary, focused on Tiananmen Square; the second gave its lead role to a student named the worst actor in class by their professor. Upon graduation Jia left Beijing and returned to his hometown in the Shanxi province of Northern China. It was here where he would centre his first three features, all of which were made outside of the state system and now go by the title of the ‘Hometown Trilogy’. The earliest, Pickpocket (originally released in 1998 under the title of Xiao Wu, the name of its central protagonist), was a low-key character portrait shot on 16mm and told in a firmly realistic fashion. Its follow-up, 2000’s Platform, was far more ambitious: an epic, near-three-hour account of a theatrical troupe as its members negotiate the sweeping social changes that took place during the eighties. Unknown Pleasures, released in 2002, returned to the present day to focus on a group of teenagers whose youthful confusion and dissatisfactions seem to mirror the enclosed world around them.

Though made with a considerably lower budget than his later features (Platform and Unknown Pleasures would secure some of their finance from France and Japan) Pickpocket nevertheless sets out the Jia style with a quiet confidence. Bookended by genuine documentary footage, the suggestion seems to be that the film itself is equally valid as non-fiction. Jia shoots handheld, utilises only natural sound and employs only non-professional performers (though lead actor Wang Hongwei would capitalise on his wonderfully charismatic performance by becoming a regular for the director). The sense of place, especially, is superbly realised: shabby suits, shitty ringtones, incessant smoking and grotty, poorly furnished surroundings. Indeed, this is as much a portrait of the city of Fenyang as it is of our titular pickpocket, which arguably only adds to the feeling of authenticity. Not only are we getting a window into little-seen aspects of Chinese lives (petty thievery, poverty, prostitution), we’re also getting a window into a part of the nation that’s rarely been captured on film, a situation that’s hardly changed since Jia’s success raised its profile.

Any hint that these are just local tales told by a local boy are pushed aside by larger concerns. Pickpocket takes place during the Hong Kong handover from the UK back to China, though it has little immediate effect on our central players. And yet it’s impossible not to discern the changes that are happening around them. Xiao’s one-time ‘business’ partners and associates are slowly going legit, crimes are being cracked down on and crumbling buildings are being evicted and pulled down – but still he stays put, unsure, unable or unwilling to adapt.

Similar tensions permeate Platform and Unknown Pleasures. In the former we see the gradual influence of Western culture, sudden surges in progress and the attendant uneasy mixture of optimism and pessimism they bring. Bell-bottom trousers are just the first sign of youthful rebellion, while the theatrical troupe go from performing anti-capitalist songs to becoming the All-Star Rock ‘n’ Breakdance Electronic Band (!). Such progress has made firm roots by the time of Unknown Pleasures but it sits among high unemployment, highways that go nowhere and only the barest hint of future promise. Amid such scenes we witness the announcement that Beijing will host the 2008 Olympic Games, though within such a desperate locale how can you fail to detect Jia’s sour thoughts on how this will affect the nation as a whole?

Perhaps aided by a growing curiosity about China in the West, not to mention his very obvious qualities as a filmmaker of course, the ‘Hometown Trilogy’ firmly established Jia’s standing on the world stage. Between them they garnered numerous festival awards and nominations (Unknown Pleasures was a contender for the Palme d’Or in 2002) as well as distribution deals across the globe. Artificial Eye had the good taste to pick up all three for UK release – they’re now repackaging them for a new DVD box set – and yet all of them remained effectively unseen in their home country. You could buy the collected screenplays or possibly find them on bootleg discs, but the chances of watching them on the big screen were non-existent. It is only in more recent years that the bans have been lifted, although this goes hand-in-hand with Jia’s own ‘legitimacy’. Since 2004’s The World he’s actively sought – and gained – state approval for each one of his features.

Interestingly this hasn’t led to a compromise in either style or subject matter. The World, set in a massive theme park of the same name situated on the outskirts of Beijing, is another sourly satirical look at capitalist folly. Viewed through the eyes of the overworked and underpaid who man its security and perform on its stages, the movie treated its characters with typically humanistic respect but never once pulled its punches. The corruption and criminal undercurrents on display were clearly speaking to wider concerns within society and the system.

Two years later Jia headed to the Three Gorges region, an area that would soon be flooded to accommodate a multi-billion dollar dam project, for the award-winning Still Life. Once again the director was able to capture a point in time just as sweeping change was taking effect, and as with previous features he did so through everyday folk and the seemingly anonymous (both of its main characters hailing from the Shanxi province).

In the same year as Still Life Jia also completed Dong, a documentary on the artist Liu Xiaodong that served as a companion piece. It too was shot in the Three Gorges region, capturing Liu as he painted workers as well as the feature film’s lead actor Han Sanming. Sharing some of Still Life‘s footage (or vice versa) it becomes impossible at times to detect where the boundaries between fact and fiction lie, an aspect which has taken on increased prominence in subsequent efforts. The documentary format has assumed a far greater presence in Jia’s filmography these past few years, whether its 2007’s Useless (about fashion designer Ma Ke), 2010’s I Wish I Knew (about the history of Shanghai) or his contributions to campaigning anthologies. Even his sole feature since Still Life, 2008’s 24 City (another nominee for the Palme d’Or), acted as a hybrid work, containing both genuine interview material and more conventional performed passages.

All of which makes the next project somewhat surprising. Like those ‘Fifth Generation’ filmmakers before him, Jia is turning his attentions to a big budget martial arts epic. Currently going by the working title of In the Qing Dynasty, this is the kind of picture that’s easy to be cynical about. Indeed, despite gaining official approval The World, Still Life and 24 City all made barely a ripple at the Chinese box office, whereas Hero became the highest grossing film in its history. Any suggestion that Jia is simply chasing the money is going to be hard to escape, although he has stated that he intends to "infuse a more humanistic message besides commercial elements". Whether he succeeds or not remains to be seen, but in the meantime we have a remarkable body of work – and particularly the ‘Hometown Trilogy’ – at which to marvel.