If you had to name Britain’s contribution to the genre of avant-garde film you’d probably think of the work of Derek Jarman and Peter Greenaway who perfected a sophisticated kind of moving painting approach to film. Both men played with surrealist set pieces, alternative narrative structures, lyrical imagery and stunning compositions. But for all their censor-baiting nudity and frank depictions of transgressive sexuality they always seemed, to me at least, a bit conservative. Which is to say that both filmmakers’ considerable arsenal of ideas was very, well, public school: Greenaway was and is still obsessed with Renaissance paintings; Jarman even made a film entirely in Latin; both seemed to revel in issues of class and Britishness and have classical music soundtracks. Jubilee may have been the first punk film but Jarman’s disdain for punk culture made it more of an anti-punk film. Both filmmakers were boundary pushing but neither strayed that far from traditional aesthetics and ‘good taste’.

So where were the real punk filmmakers? Where was the D.I.Y., burn everything and start from scratch, ‘anyone can make a film’ kind of attitude? Where was Britain’s answer to the shoot from the hip No Wave cinema or uncompromising Brakhage style experiments? One could argue that Ken Russell, (also steeped in classical allegory) was quite punk: more iconoclast than iconic. But even he was no match for the likes of Jeff Keen.

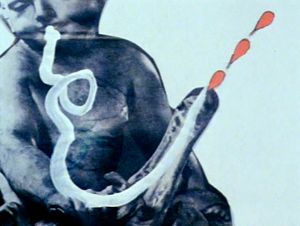

Jeff Keen was making insane film mash-ups while Russell was still paying his dues at the BBC. Upon seeing Marvo Movie, one of Keen’s first films, Russell was famously quoted as saying, "It went right over my head and seemed a little threatening, but I’m all for it." Marvo Movie is just as jarring a watch today. It’d be easy to write the whole thing off as a five minute wank if it weren’t so fucking good. It’s like a really long Ken Russell-esque surreal montage but made out of paper and kitsch travelling at breakneck speed to a soundtrack that sounds like Nurse With Wound. As his style ‘matured’ he somehow managed to cram even more media – cutouts, stop motion animation and melting toys – into the mix, all sped up, solarised or double exposed until the people and cartoons become indistinguishable. Keen’s rapid-fire images appear just long enough to burn themselves into your subconscious like subliminal advertising. You find yourself laughing at wordless jokes that you can’t explain and you dare not blink because if you do you’ll miss 15 more such jokes.

You’d think that Jeff suffers from ADD but it’s probably more like Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. As a soldier in WWII, Keen worked mainly on tanks preparing for the D-Day invasion. Freud talks about how the victims of trauma are condemned to repeat endlessly their trauma in an effort to master events which were once out of their control. You can certainly feel a compulsiveness in the way Keen layers his images and replaces, say a gun, with a gun made out of dismembered barbie dolls. His films are pure chaos but a chaos of his own design, meticulously constructed, brick by brick. There is also a churning rhythm to most of his films. Each wave of senseless drawing-fits inevitably ends with one character eating or fucking another and the whole scene consumed by fire before it starts again.

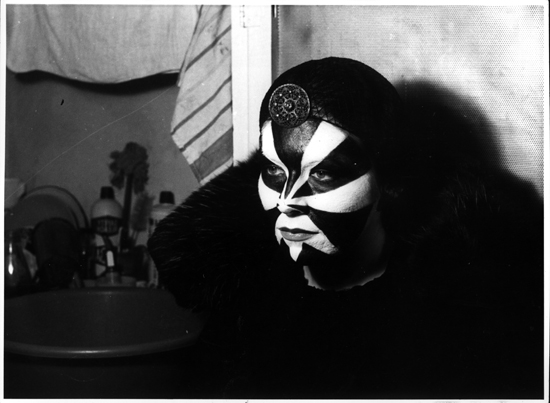

If you watch enough of these films together you start to recognise his pantheon of recurring characters: the Cat Girl, Vuluptua, and of course Kino himself. You also start to recognise familiar scribbles, such as the cryptic cloverleaf shape (resembling a double set of cock and balls), which attains a certain gravity after the 100th time you see it.

Keen’s childlike, obsessive creativity and love of pure nonsense makes his films very Dada-like (if there ever were true Dada cinema) which is surprising since he was 37 when he made his first film in 1960 to fill space in his local film society programme. It is probably that age difference that makes his work so different from the feel-good psychedelia of the baby boomer generation. While the 20 something hippies were uncritically embracing whatever utopian idea would get them laid, Keen had already experienced the darker side of humanity. You can see this critical detachment in one of his earliest films Like the Time is Now which makes fun of the beatniks in a cutting, slapstick manner.

Keen embodied the punk ethos before punk. His spare use of words, e.g. – "Like, the electricity is melting man", "This is the copy where’s the original," "The Film of the Book!" – is very similar to that of Punk’s first artist Raymond Pettibon, who also drew heavily on Dada. He can also be seen doing graffiti and stencils, defacing advertising long before Keith Herring made a career out of it. He was even filming disturbing, mask-wearing performance art before Paul MacCarthy.

The cacophonous ‘music’ is also worth mentioning. Just like the images it is formed out of layers and layers of found material, pure noise and the occasional drum machine, integrating distorted schlock-horror vocal samples before Cabaret Voltaire made that cool.

In his massive body of work, which totals about 9 hours and fills 4 DVDs, there are some missteps: sometimes the images fail to grab you for a minute, sometimes the onslaught of art is too much to comprehend, like visual white noise. Keen was in his element with 8mm, the perfect D.I.Y. medium, just grainy enough to blend the joins in his collages, so understandably his first forays into camcorder technology are a bit unsteady (although he certainly wasn’t timid about giving it a try). But then with Art War, originally broadcast on Channel 4 in 1993, he regains his swagger, no doubt spurred on by images of the first Gulf War. In Art War the military subtext rises to the foreground with a deafening explosion-laden soundtrack all careening past in a breathless 6 minutes. Even at the age of 60 he could be just as confrontational, edgy and funny as when he began.

It’s exciting to discover that their was another wave of British experimental film operating just under the radar all this time. With his films finally available to own, we can only hope that a new generation of artists and filmmakers can throw their film school teachings and aesthetic preconceptions out the window and produce films that are as visceral and slap-you-in-the-face original as these lost gems.

GAZWRX: The Films of Jeff Keen is released by BFI films on 23 Feb

The BFI Southbank will be screening a selection of his films now until 27 Feb.