When British film maker Jeanie Finlay released the documentary The Great Hip Hop Hoax in 2013 something very curious happened.

The film is a fascinating, surreal, uncomfortable and ultimately touching portrayal of the ‘rise and fall’ of two Scottish rappers Gavin Bain and Billy Boyd who pretended to be American in order to reinvent themselves as Silibil ‘N Brains thus securing a quarter of a million pound record deal.

But despite featuring plenty of archive material and talking head interviews with dozens of music industry figures, a story started to circulate that the film itself was a hoax.

Users of social networking sites such as Reddit started floating the theory that the whole thing was a sham and connected with enough like-minded people that a bona fide conspiracy theory – which stated that all the main players in the film, including Finlay, were actors – began to take root.

I became aware of this strange turn of events when, after I’d written about the film for VICE, I received an email from a regular reader, who angrily demanded to know why I’d fallen for such an obvious con.

I told him that the idea was crazy, that Jeanie Finlay wasn’t – as far as I could tell – an actress. I’d met her several times and she had several other films under her belt. More to the point, some of the music industry figures interviewed for the film were actually quite famous. Quite Google-able.

His response? "Nah, I don’t buy it… none of it adds up."

The worst thing about this conspiracy is even though it’s utter bilge I can kind of understand it. Finlay seems to have a knack for plucking amazing stories out of the ether. This is certainly the case with her latest film Orion: The Man Who Would Be King as well as The Great Hip Hop Hoax. They both have the kind of incredible story that leaves you thinking: "Why haven’t I heard of this before?"

If the story of Orion had been presented as fiction it would have stretched most people’s credulity beyond breaking point. Jimmy Ellis was a farm boy from Orville, Alabama who was blessed/cursed with a singing voice that made him sound incredibly like Elvis Presely and a determination to become famous, under his own steam, at any cost.

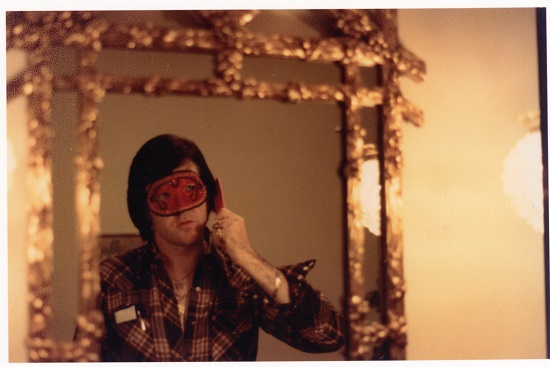

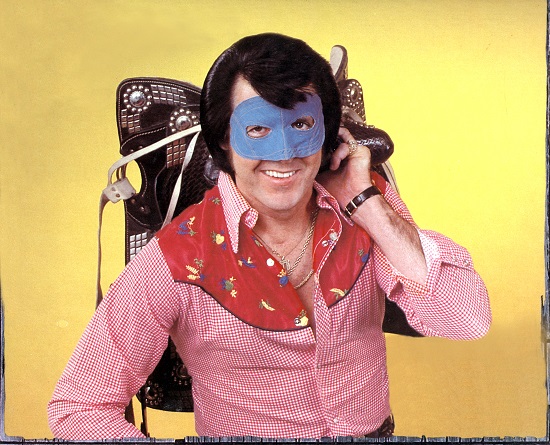

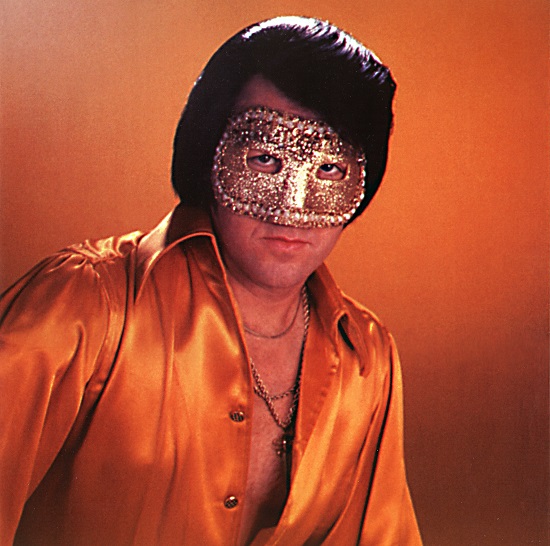

After the death of Presley in 1977, the Machiavellian boss of Sun Records, Shelby Singleton persuaded Ellis into a contract which meant he would always have to wear a mask in public and always have to guard his true identity.

From that point on Ellis was for all intents and purposes Orion and Shelby did everything but tell the public that this strange masked man was Elvis reborn. Enough people believed it – or wanted to believe it at least – that he became a sensation in the southern states of the US, selling over a million records, playing to packed houses for years to follow.

And my first response to hearing all of this? "Why have I never heard of this guy before?"

But it’s not just a knack for digging up interesting stories that makes Finlay such an especially talented film maker. As Orion (and her documentary about a Stockton-On-Tees record shop Sound It Out) shows, she has a knack for filming ordinary people and finding out extraordinary things about them as well as humanising characters that many would initially find unsympathetic, gauche or unremarkable. She locates heroism in the quotidian, among the overlooked. As such her films tend to (genuinely) transcend their apparent subjects (they are nearly always music related) to tackle bigger, more universal themes of what it means to be human.

I interviewed Jeanie in London recently, as Orion: The Man Who Would Be King has now become available to watch or buy via iTunes.

Photography by Steve Kelley

I’m pretty sure I’d never even heard of Jimmy Ellis or Orion until you mentioned him to me in conversation about three years ago – even though he was, relatively speaking, a big deal at the time. I was wondering where you find these strange stories and how many of these ideas do you go through until you find one, that you can put into production?

Jeanie Finlay: With Orion it felt like Jimmy Ellis was always there. It came from being with Steven [Sheil, film director, husband] at a car boot sale about 12 years ago. We get competitive about who can buy the most interesting thing – books, comics, records, that sort of thing. And one day I found an Orion record – the blue version of Reborn. I took it home and read all of the information on the back of the sleeve and this raised a question about who he was for me. When I looked into it, there was only one article on Jimmy Ellis on the internet written by Mike McCall who appears in the film. So all I had was the bare bones to the Orion story. And I just forgot about it because I wasn’t even making films back then. It wasn’t until six years later I began to think about it [in terms of a potential film].

But in general terms of what stories will make a film, it’s massively instinctive and unscientific. I will be struck by a feeling of, “Yeah, that’s totally a film.” And sometimes it’s a creeping certainty. Sound It Out developed slowly out of a joke. I would go home [to Stockton-on-Tees], it would be terrible apart from going to the record shop with my daughter. I’d joke to Tom [Butchart, owner of Sound It Out records], “Oh I’m going to make a film about this shop.” And sometimes I feel it’s about having confidence in my own ideas – having the confidence to test them out. So I just kind of turned up at the shop one day and started making a film. With Orion it always felt like it could be a film. With The Great Hip Hop Hoax it felt like it could be a film. With Panto! I was watching a production of Aladdin and during the interval I was watching the people on stage and was thinking, “I wonder what their lives are like – I wonder how they got here.” And I couldn’t stop thinking about it. So I don’t have a massive long list of ideas that I’m constantly throwing out, it’s more like I fall in love with an idea and then remain devoted. Sometimes I think that being a filmmaker is a test of your own resilience and relentlessness. You have to be relentless in the face of people telling you there’s no audience for your idea or that it’s boring.

Obviously with your films you start with an interesting proposition but are you relying on something else clicking into place after you start filming?

JF: Sometimes it’s just a matter of trying stuff out. For example when I started off doing Orion I knew the bare bones of the story but I also knew whether it would make a film or not depended on the people that I met and on the archive material I could source. But as soon as I started filming and I got a sense of this man that I would never meet coming to life, I felt pretty early on, “Yeah, there’s somewhere to go here.” Early on you need to make a decision about what kind of film you want to make. With Sound It Out I always knew I wanted to make a portrait. With Hip Hop Hoax I always knew there was a driving narrative. But with Orion I thought it would be a mix of the two things. I shot another film this summer about Indie Tracks the strange and wonderful music festival that takes place on a heritage railway line and originally I thought it was going to be about conflict between these two very different groups of people but it became clear very quickly that it wasn’t and it was in fact about nostalgia and vintage passions and how that shapes people’s lives. You have to fine tune your emotional awareness when you’re interviewing people. I do all of my research, I write it all down and then I just listen to what they have to say.

Speaking as one interviewer to another, I’m really jealous of your ability to make people open up. What’s your secret?

JF: [LAUGHS] I’m always amazed at how open people are. I do genuinely love interviewing people. I’m not pretending to be interested in them which really helps I think. I think I’m a stranger in the situation, so I go to places where I’m out of place and I think that helps. When I was doing Goth Cruise, people asked me, “Are you going to goth up?” But I’d say, “Don’t be ridiculous – can’t I just be myself?” And I think maybe I am just a better version of myself. Less sweary. More punctual. And I feel like the interview happens in the space between [the subject and me], so there’s chemistry or sometimes it leads to people telling me about things that are really hurtful or upsetting. People cry all the time or I end up crying. It’s very emotional. Also a lot of people say they forget about the cameras during the interview, which when you’re talking about a two camera set up with lights, is really good.

In terms of archive material do you feel like you landed on your feet with Orion? It feels like there was a lot of material for you to work with, especially photographs.

JF: It got better as the process went on. I went through layers and layers and layers of the fan community surrounding Orion.

How big is the Orion fan network these days?

JF: It still exists. It’s not huge by any standards. There are probably 300 people in the Orion fan network that I belong to; that I speak to. I don’t speak to them every day but every week.

What do they think of the film?

JF: Some of them are totally frustrated because it’s not out in America yet. There was a lot of trepidation and worry but then some of them came to Nashville [to see a screening] and they loved it. I was very worried about this beforehand because it’s not a hagiography in any way. But I think people responded to the fact it was true. It’s a lot of micro-communities which are connected by this bigger Venn Diagram. I feel like they’ve really taken me to their hearts but that took years. They were quite suspicious of me at first. And quite rightly so.

When you start doing something like Orion do you ever have a feeling along the lines of, “Why has no one already done this?”

JF: Totally.

Because I’m totally flabbergasted that I’d never heard of this before meeting you.

JF: I was really surprised myself. I found the story in the act of buying a record at a carboot sale. The story was there it was just that no one had noticed it before. So it felt like magic – like something I could do. There was talk of someone making a fictional feature film out of the story and then another documentary maker started doing their own version of Orion after I’d started doing mine but that didn’t come to anything. I’d gotten so far down the line and had gathered up so much material and had interviewed so many people who are now no longer with us. I was on a one way journey by that point. I had to finish it.

What do you think would have happened to him had he not met Shelby from Sun Records who persuaded him to put on the mask?

JF: I honestly don’t know. I get the sense that he never would have been fully satisfied. It wouldn’t have mattered what else he achieved in his life, he would never have been able to put out that fire inside him – this burning desire to become famous. This fire inside him was never going to get put out no matter how much he drank or how many women he slept with. I get the sense it’s like the X Factor conundrum. Is it enough to be able to sing down the pub in front of your mates or do you have to become well known for having that talent? Because then when you feel you have to become well known you enter into this whole industry which is about so much more than just being about whether you’re a good singer.

Even if you only take a cursory look at any of the many, many photographs there are of Jimmy Ellis as Orion, it’s really clear that he’s not Elvis isn’t it?

JF: Yeah, totally.

We’re talking about some kind of strange psychological phenomenon really aren’t we?

JF: I think it was a really appealing lie that came around at the right time in the right place. And Shelby Singleton was there to capitalise; and really he had no qualms about playing on people’s emotions. For example, he got Boomer Castleman – Orion’s guitarist – to write a song called ‘John’ on the day that John Lennon died and they got it out really quickly. Before his body was even cold. But yeah, the fact that he doesn’t even really look like Elvis makes the story even richer. There was a three way fantasy going on. Jimmy didn’t believe that wearing the mask would affect his career or his life and that by being Orion his dreams of being famous would still come true. Shelby was spinning a fantasy to the public, and then the fans were spinning their own fantasy. “Well… he doesn’t look exactly like Elvis but maybe… just maybe…” And it was enough. That three way fantasy was held in place in the flimsiest of ways. It was a weird alchemy of fantasy and lies.

To me, in some ways, Orion is like a glimpse into a bygone age where pop music had precedence over nearly any other means of entertainment you could care to mention. It’s impossible to conceive of an Elvis-like figure happening now so by extension it’s even more impossible to conceive of an Orion-like figure happening now.

JF: I’m not sure really. The thing about Orion that allowed it to happen was that he was a real phenomenon in the southern states of the US and he travelled from town to town to town. Orion happened pre-Google so it was a word of mouth thing. So you’re being told by believers to believe. When you have a group of fans, the alchemy isn’t just directed at the man on the stage, it’s directed outwards as well. People found lifelong friends through being his fan. Also they could get close to him in a way they could never get close to Elvis Presley. There was a real kindred spirit. What’s strange is today we have stars like Taylor Swift – and in terms of music sales she’s massive – but as for perpetuating that kind of hoax? I’m not sure that they could.

How did you feel about Jimmy Ellis once you found out about his promiscuity and his trophy keeping and things like that?

JF: I don’t know. It was weird. There was one thing that would happen in every interview I did and someone would always lean over and say conspiratorially, “He loved women… he would have loved you.” And I don’t know if I’m supposed to feel good about that. It was quite strange really. My feelings about him really changed and flexed as I met different people. I don’t think you have to like someone to make a film about them, you just have to find them compelling and feel empathy for them. But he was supposed to have been very charismatic. People speak about him with such love, he was truly charismatic.

How do you approach filming America as an outsider? I’m really impressed with this feel you have for downhome USA. Not just in Orville, Alabama but in places like Nashville as well. How long did you spend shooting all of your cutaways? How long were you there in total?

JF: I was probably there for five weeks over the space of three years. It’s not that much. My cameraman is called Stewart Copeland and he’s a rock drummer [LAUGHS]. He’s in a band called Bully who are signed to Columbia. He’s from Tennessee, and he and I would spend a lot of time filming. Let’s put it this way, I spent a lot of time on porches drinking strong drinks out of glass jars. I think if you don’t know a place, sometimes the things that are really obvious about it become apparent straight away. It’s a cliche but there was the Spanish moss and I kept on thinking about this in terms of it being a trap. Also being a Northern wuss, I was too hot all the time, so I wanted the film to feel very hot because it’s boiling in the South. There are also all of these impressive antebellum houses that have been taken over by nature. I don’t think you should be afraid of showing obvious things. We shot cotton fields because they’re everywhere. We shot the house where Jimmy Ellis grew up in minute detail. There was this hornet’s nest we shot in minute detail, and I don’t think it’s even in the film. In the opening credits we have a shot of Orion walking through a field of lights because I had a dream about it [LAUGHS]. It was shot in a light installation called Submergence in the Lux gallery, Oslo. There was this artist called Squidsoup that I really like and they were like, “We’re setting up in Oslo, so if you can get out here you can shoot for as long as you want.” So I managed to raise some money and went to Norway. We got Norway’s most famous Elvis tribute artist and we filmed him walking through the lights for hours. No one actually needs to know any of this when they’re watching the film! But some of those sequences did take ages to do.

Have you accidentally ended up as a female director who is extremely adept at portraying what’s wrong with men? I mean, I take it this was never an aim of yours?

JF: No. The films take so long. When I started filming Orion – I couldn’t get anyone to fund it. Then I started filming Hip Hop Hoax and we hit a legal wall. I made Sound It Out and then I made Panto! and that’s when Orion got funded. So sometimes it might be that you had a notion six years previously. And maybe you only see these patterns retrospectively. So even the whole music documentary thing is quite weird as that had never been my mission. You know, I make films about things I’m obsessed about. And I’m obsessed about the grit under the glitter. The idea of the depth you can find in pop culture. The deep emotional impact in a seemingly frivolous story. You’re committing five years of your life to something so it had better be something that you’re obsessed with. But the whole male thing? I don’t know. I’m purposefully making my next film about a woman.

What’s your favourite Orion song? Does any of this music have any kind of intrinsic value for you?

JF: It’s weird because I only listen to this music for its narrative value but I really love ‘Honey’. I think that song is amazing and spooky. It could be in a David Lynch film easily. I love the production on it. I really like ‘Don’t Judge A Book By It’s Cover’. I’m doing an Orion EP in December to go with the DVD and I’ve just been really selfish and chosen four tracks that I like. My choices are: ‘I’m Not Trying To Be Just Like Elvis’, ‘Honey’, ‘Don’t Judge A Book By It’s Cover’ and ‘Georgia Pines’.

Orion: The Man Who Would Be King is now available to buy or hire from iTunes