Permanent Vacation, the 1980 feature-length debut from American auteur Jim Jarmusch, is possibly the most directionless entry in a filmography defined by lyrical aimlessness, and is almost certainly the director’s least seen and celebrated work. One of the finest films in the entire “young dude walks around in search of enlightenment, finding only surreal situations” genre, it follows vacant, born-too-late bebop kid Allie (played by non-actor Chris Parker) as he stumbles from one gloriously decayed New York locale to another. It’s the film where nearly every piece of Jarmusch’s aesthetic was developed, and possibly the best time capsule of punk-and-hepatitis Manhattan ever committed to celluloid.

That it’s most readily available as an extra attached to Criterion’s edition of Stranger Than Paradise tells you plenty about Permanent Vacation’s reputation. Hardly any real scholarship has been devoted to the film, which Jarmusch made before leaving NYU’s film program sans degree. In an insightful and glowing review of …Paradise that supplements the aforementioned DVD release, noted film critic J. Hoberman dismisses Permanent Vacation as “a plotless portrait of a teenage drifter.” Meanwhile, Jonathan Rosenbaum, one of the most reliably perceptive of all film journalists (and a champion of Jarmusch’s), referred to the effort as “apprentice work,” lacking in “characteristic charm, stylistic focus, and feeling for interactions between people.” Reverse Shot’s Nick Pinkerton provided what is probably the most evenhanded, thoughtful take on the film, though he also chides it for being “draggy.” But it’s just that anti-plot quality which deserves investigation. Because it’s here that we can see the beginnings of that most ineffable yet vital aspect of Jarmusch’s cinema: A slowness that suggests a constantly wandering consciousness, one untouched by anything but the basic need to just keep moving in search of something unnameable.

…Vacation unfolds as a series of unhurried snapshots from Allie’s life, which Jarmusch simply allows to play out. The film’s parade of morbid eccentrics and glamorous psychotics suggests a street-level Chelsea Girls. There are also vague references to unseen warfare and bombings on American soil, with real urban locations standing in for dystopian backdrops in the tradition of Eraserhead and Godard’s Alphaville. Yet Jarmusch shows no real interest in developing these sci-fi shadings, seeming as concerned with roving around rotting flats and vacant lots as he is with revealing the people who inhabit them. Already, in his first feature-length, we can sense the filmmaker wandering away from the influence of art house monuments, and into a headspace that couldn’t be mistaken for anyone else’s.

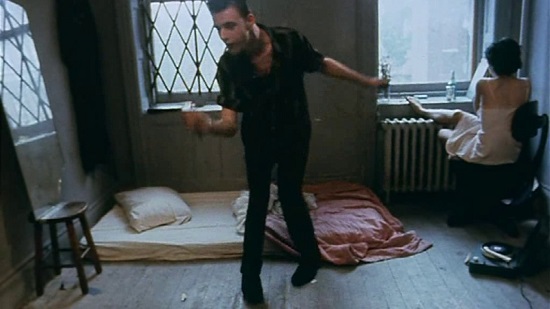

Jarmusch conveys Allie’s waking-dream mindset through languid real-time pacing. Just as in the cinema of a Melville, Ozu or Wenders, it’s this gradualness that becomes the film’s most significant characteristic. Allie is often seen walking the full length of static frames. He asks a barely-there theater cashier whether or not he should buy a ticket for Nicholas Ray’s The Savage Innocents, and she replies by describing multiple scenes from the movie at length. When he picks up a copy of Le Comte De Lautreamont’s proto-surrealist book Les Chants de Maldoror, we watch as he reads full pages of it aloud. And in …Vacation’s most memorable vignette, the nearly comatose Allie briefly springs to life to perform a show-stopping dance that lasts just about the entire length of a spaced out solo from alto sax legend Earl Bostic. As our protagonist, propelled by an obscure desire he simply calls “the drift,” moves through these episodes, his journey begins to feel like a parallel to Jarmusch’s own endless pursuit of coolness.

Which isn’t to say there’s anything conceptual or even remotely self-aware about this freeform, rough draft of a film. It contains no shortage of lines delivered in earnest that tend to draw unintended audience laughter (“I think I should just live fast and die young”). The film’s price-of-a-used-car budget is never less than apparent. There are awkwardly bumpy zooms, even more awkwardly bumpy performances and the sound mixing is spotty at best. But it’s these exact attributes that make the Lower East Side of 1980 feel all the more tangible, and allow …Vacation to work as movie that is ultimately about hanging out and just observing.

Like D.A. Pennebaker’s classic Dylan documentary Don’t Look Back, it’s the kind of film you can return to year after year because of its ability to conjure a very specific time and place. Sure, there’s Blank Generation and those slices of narco-NYC vérité from the likes of Warhol/Morrissey and Amos Poe. But those offhanded, trashy visions don’t really allow us to luxuriate in crumbling settings the way …Vacation’s deliberate pace does. Jarmusch’s eye for elegantly desolate compositions was already masterful at this point, and there’s just no better way to absorb the rubble of vintage, junkie’s paradise New York than via one of the director’s signature lateral tracking shots. Perhaps no filmmaker has been more routinely compared to musicians, and here he’s operating on an elevated, lyrical wavelength closer to that of Television than Lou Reed or New York Dolls. If …Vacation had been more widely screened in its day, you could imagine art punks everywhere copping Allie’s style and Jarmusch’s taste while attempting to translate their own shitty surroundings into poetry.

And while …Vacation has a distinct value all of its own, it’s also worth noting that lines can be drawn from this debut to every subsequent film in Jarmusch’s oeuvre. The episodic structure would become the director’s hallmark storytelling technique. Lily-white Allie, who looks like he wandered out of the cover of the Feelies’ first album, is presented, without mockery, as a “wild style” jazz hipster who looks up to Charlie Parker. This fondness for cross-culturally obsessed misfits has surfaced again and again, from Ghost Dog’s titular hero to the Americana-loving Japanese couple of Mystery Train. …Vacation’s closing scenes, in which a Paris-bound Allie meets a French hepcat newly transplanted to New York, mark the beginning of Jarmusch’s fascination with the chance encounters and partings of doppelgangers and inverses (the parting shot of Down By Law is but one echo). And wandering, existentially inclined central characters figured in numerous future triumphs, from Paradise and Dead Man to the unjustly maligned The Limits of Control. Likewise, the moody atmosphere derived from real city environments extends right up to the director’s latest work, Only Lovers Left Alive, which teased post-apocalyptic dread out of present-day Detroit’s lower depths.

Allie’s final voiceover even forecasts the conversations of Adam and Eve, the vampires from that latter-day effort who subsist on a diet of blood and endless cultural foraging. “Let’s just say I’m a certain kind of tourist. A tourist that’s on a…permanent vacation,” he monotones, with forced emphasis on the film’s title. It’s a moment that’s likely to elicit groans and cackles from modern viewers, and admittedly, it’s painfully obvious and goofy as hell. But, oddly enough, those very lines which end Jarmusch’s weirdly entrancing student film now sound like a mission statement for the director’s own restlessly inspired career.

Permanent Vacation is showing tonight as part of the BFI’s Jim Jarmusch season https://whatson.bfi.org.uk/Online/default.asp?BOparam::WScontent::loadArticle::permalink=jimjarmusch