The rise of the music video coincided with the rise of the VHS – inevitably, the two quickly became firm friends. At one point during the early eighties, Making Michael Jackson’s Thriller could call itself the biggest selling videotape of all time, and this despite it being a mere hour-long documentary on the creation of a promo. Though both formats were relatively new, certain bands and labels were savvy to the creative opportunities. Mute Records, for example, established Mute Film and put out the likes of Johnny YesNo (a 30-minute noir pastiche soundtracked by Cabaret Voltaire) and Halber Mensch (which teamed up cult Japanese director Sogo Ishii with Einstürzende Neubauten). Duran Duran and ABC both conceived of concert hybrids: Arena mixed live footage with science fiction, while Mantrap opted for debonair Cold War thrills. Others would simply turn a single promo into a mini-movie, as with David Bowie’s Jazzin’ for Blue Jean, or do much the same with an album’s worth, as Kate Bush did with The Line, the Cross and the Curve. The latter, incidentally, received its premiere at the London Film Festival, but these were very much intended-for-video affairs. Indeed, most have since slipped away into obscurity thanks to the VHS’ obsolescence. Unable or unwilling to make the DVD upgrade, many remain firmly in the domain of the collector or the memory of the long-term fan.

Not all of the tapes that occupied the music section were quite so inventive. Plenty of them were simply content to throw together a bunch of vids with maybe the odd bit of live material and call it a day. Picture Music International, the visual arm of EMI, did just that, regularly releasing such titles as Marillion: The Video EP and Cliff Richard: The Videoconnection. Their first Pet Shop Boys VHS, Television, did much the same (six promos and nine snippets of TV appearances in the space of half an hour) and there were similar plans for tape number two. Except the band’s visual ambitions had started to expand. Soon there would be collaborations with Derek Jarman (a Turner Prize nominee by the time he’d directed promos for ‘It’s a Sin’ and ‘Rent’) and Polish animator Zbigniew Rybczyński, not to mention more ostentatious plans for their second VHS.

Jack Bond was the director of choice and an interesting one. Between 1967 and 1979 he had made a trio of features (plus one short) with his partner Jane Arden. These were difficult films and deeply personal with it, experimental in nature and heavily linked to Arden’s mental health. (I wrote about them in greater detail for the Quietus last year.) When she committed suicide during the Christmas of 1982, Bond effectively suppressed every one of their collaborations. You couldn’t find them in the shops or on the telly, while requests for film festival screenings or one-off repertory showings were all refused without question. They eventually resurfaced in 2009 thanks to the British Film Institute, but when Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe came calling 20-plus years beforehand the only works of his to have been readily available at the time were his contributions to The South Bank Show. To those who recognised his name, Bond was more likely to be considered a maker of television, not a maker of films.

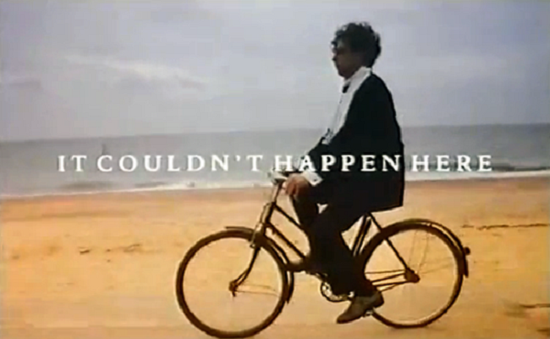

With that said, there was no intention – initially, at least – for It Couldn’t Happen Here to represent a return to features. Long before it had a title, it was conceived as a collection of interrelated music videos that would combine into a single narrative. Much like The Line, the Curve and the Cross, in fact. Yet with Bond installed as producer and co-writer as well as director, the project grew into something much larger and, it must be said, far stranger. Perhaps feeling a little creatively starved from making hour-long documentaries about Catherine Cookson and Roald Dahl, here was a chance to properly reinvigorate those talents which had made the films with Arden so extraordinary. Not that The South Bank Show format should be dismissed out of hand; Ken Russell was doing some interesting work within the strand around the same time too.

While Bond and Russell were working in television, a new generation of British filmmaker had begun to emerge keen to offer up their own distinctive brand of highly visual cinema. There was Jarman, who had earned two of his first professional credits as a production assistant on Russell’s The Devils and Savage Messiah, and there was Peter Greenaway, who somehow managed to translate his incredibly avant-garde sensibility into commercial success. They were also a mere five years older than Bond, which may just have spurred him on too. He would be able to compete with the likes of Caravaggio and A Zed & Two Noughts, to demonstrate that he once had the potential to be in their position. Those films with Arden had been perfect syntheses of style and content, whether it was the pristine surfaces of Separation gradually slipping into confusion (to mirror its central character’s breakdown) or the uneasy fusion of reality and performance that made The Other Side of the Underneath such a riveting – and oftentimes difficult – viewing experience. But then the Pet Shop Boys were likely to make for an entirely different collaboration than those Arden had allowed for…

It Couldn’t Happen Here went under the working title of A Hard Day’s Shopping, an overt nod to the Beatles’ 1964 movie via a cheeky wink to one of the tracks off second album Actually. Much of the film’s soundtrack would come from that LP (plus a couple from debut Please), but the reference to A Hard Day’s Night is perhaps misplaced. That was all about the larks, whereas the Pet Shop Boys feature had slightly more erudite concerns. Its true lineage can be traced back to Catch Us If You Can, essentially an attempt to replicate the Beatles’ big screen success with the Dave Clark Five, only it found itself with John Boorman as director and Peter Nichols as director. Having the men who would later be responsible for, respectively, Point Blank and A Day in the Death of Joe Egg in charge meant an oddball, disjointed affair with existential leanings and plenty of surrealist touches.

Indeed, such a description fits the bit for It Couldn’t Happen Here too. The film opens in Clacton-on-Sea and slowly proceeds to London. (Catch Us If You Can provided a road movie in the opposite direction, taking us from the city to the sea.) Tennant and Lowe serve as lonely wanderers, initially apart, who barely interact with the madness that surrounds them. This isn’t a social realist England, but rather a construct of cultural reference points: saucy postcards, beachside biker gangs, Carry On movies (Barbara Windsor co-stars), the cheeky nudist pics of George Harrison Marks – and that’s just in the opening scenes. There will soon be end-of-the-pier entertainment, a stiff-upper-lipped RAF pilot and a brief one-shot appearance by the mostly-forgotten British hip-hop outfit X Posse. All the while the Pet Shop Boys slip in and out of song; even Windsor gets to lip-synch the Dusty Springfield parts to ‘What Have I Done to Deserve This?’.

Stylistically, Bond would appear to be taking his cue from Federico Fellini. A scene in a strip revue pinches a visual quirk from Toby Dammit (the Italian director’s contribution to Eurohorror anthology Spirits of the Dead) and much of the atmosphere is akin to those phantasmagorias created in Satyricon, Casanova and more besides. The overriding presence is that of Amarcord, Fellini’s 1973 love letter to his own childhood growing up in a small coastal town during the thirties. Tennant and Lowe spent their youths by the sea too – in a North Shields fishing port and Blackpool, respectively – and find their younger selves represented onscreen. Except the nostalgia which gave Amarcord such warmth is nowhere to be found. Their schoolboy equivalents are harangued by Joss Ackland’s blind priest, who later appears as a punning serial killer: “I’ve just been fishing with Salvador Dalí. He used a dotted line.”

Needless to say, It Couldn’t Happen Here is a somewhat dark, dour experience almost in spite of the number one singles and Arlene Philips choreography. Bond delivers lyrics as downbeat narration (Tennant is on voice-over duties, naturally; Lowe doesn’t open his mouth until the halfway point) and nabs a monologue from Canadian philosopher William Newton-Smith. There’s also a creepy ventriloquist’s dummy, a commuter on fire and the Pet Shop Boys evading gunfire. Meanwhile, any humour is of such an arch, downmarket variety that it becomes firmly wrapped in inverted commas. At times it seems to make no sense whatsoever – the sharp, almost surgical coherence of Bond’s Separation is entirely a thing of the past – but the overall effect is never less than fascinating. What other film offers up muscle men, mud wrestlers, thigh-flashing nuns and the fleeting glimpse of Neil Tennant in a tasselled gold lame suit? If a DVD or Blu-ray ever emerges then perhaps a director’s commentary can iron out some of the confusion. Until then it’s more than enough to marvel at the visual richness and sheer audacity of it all.