Irreversible is a film that represents a certain quandary – it is a film that is so staggeringly difficult to watch that it casts a long shadow of doubt over recommending it to others, and indeed anyone who, having read this essay, may decide to watch it should do so advisedly. When it premièred at Cannes in 2002, large chunks of the audience abandoned it early and there were even reports of people being physically sick. It is not entertainment; it transcends that, as masterpieces of an artistic medium often do.

At the alternate polarity there is the strong conviction that this is a film everyone should watch if only ever once (and once, for most, will be enough). It is a film to be considered of vital importance in terms of philosophy and temporality, and demonstrates a filmmaker pushing at the very outer reaches of what cinema is capable of expressing.

Perhaps more importantly, it is a commentary on sexual politics, on masculinity and femininity, and whilst one might be very trepidatious about applying the label of a ‘feminist film’, it certainly observes the credo of J.G. Ballard when he said he aimed to “rub the human face in its own vomit and force it to look in the mirror.”

Ostensibly a film about rape and revenge, the narrative progression is reversed, bookended by the overriding dictum that ‘time destroys all things’, so that we see segments of time over the course of a night moving from the future to the past.

Explaining the night forwards, Alex (played by Monica Bellucci) and Marcus (Vincent Cassell) are an amorous new couple who attend a party with Alex’s ex-partner Pierre (Albert Dupontel). Tiring of Marcus’ intoxicated state, Alex decides to head home, on the way passing through a subway tunnel where she is subjected to a horrific sexual assault. Learning of this, Marcus and Pierre proceed to try and track down the perpetrator which leads them to The Rectum (the kind of place that looks like a Dante and Marquis de Sade joint venture project), in which they carry out their violent revenge.

The technique employed by Noe in reversing the chronological sequence of events is profoundly effective, changing the entire perspective through which the audience respond to the later brutality towards Alex. From the start we are plunged into a claustrophobic and hellacious sex dungeon, disorientated to the point of nausea by Noe’s flailing camerawork and Thomas Bangalter’s mind-scraping low-frequency soundtrack. The sickening act of violence carried out by Pierre on a man (mistakenly) believed to be ‘la tenia’ (the tapeworm), is seen by the audience entirely out of context, such that we can only recoil, uncomprehending of how such savagery can have been remotely justified.

By separating the act of revenge and forcing us to view it in isolation from the act that inspired it, we approach weighed down with none of the moral difficulties that would otherwise be applied. What this means is that by the time we have endured the horror of Alex’s assault, we are transplanted straight into the reactionary psyche of Marcus and Pierre and are forced to view the earlier act of violence through the prism of our subsequent moral response.

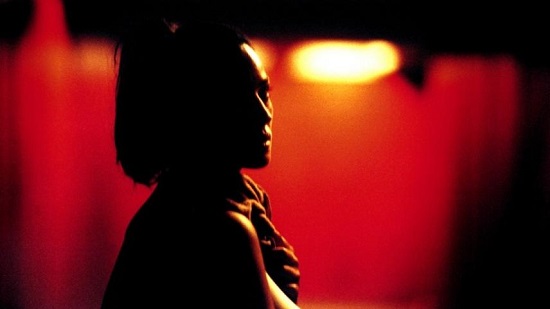

By the time of the scene at the party, we see Alex properly for the first time. She is the very epitome of sensuality and femininity. In complete opposition to the previous scene she is in complete control of herself, dancing with girlfriends gracefully and unselfconsciously, whilst Pierre and Marcus can only watch from the sidelines. As it is though, just as our perception of revenge is inverted by the chronology, so too is our perception of sexuality, we now view Alex on the dance-floor separated through a transparent screen (another recurring image) by our awareness of her fate.

It is this damning emphasis of scopophilia (deriving pleasure from watching) that magnifies the film’s judgement on masculinity and femininity. In Laura Mulvey’s 1975 essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ she views the passive role of women in cinema as a means of arguing that the film provides visual pleasure through scopophilia and identification with the onscreen actor. The woman’s inherent ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’, as Mulvey puts it, is a central issue in reducing her role to being the ‘bearer of necessity’ not the ‘maker of meaning’.

In Irreversible, the fact that Alex is placed so prominently is integral to her centrality as the ‘maker of meaning’; in contrast to what the philosopher Jacques Derrida would term ‘phallocentric’ representation – the privileging of the masculine in the construction of meaning.

Of course, the notion of Irreversible being a feminist film is contentious, but at the very least it is an anti-male one. Every male character is reprehensible and weak in their own way – they are lustful, brutal and desperate to exert power over others no matter how destructive the consequences. They are obsessed with pride and status (the rapist repeatedly refers to Alex being of a ‘higher class’ than he). They are, in the case of Marcus, obnoxious and loutish; or, in the case of Pierre, pseudo-intellectual and persistently lewd as he presses Alex for details of her and Marcus’ sex life.

Indeed it is significant that Pierre is the character who carries out the dreadful violent assault that we see at the start of the film, given that in the following scenes he is desperately trying to reason with the uncontrollable Marcus who is bent on immediate revenge. Pierre is the reluctant companion, high-minded and aware that violent retribution is futile yet unable to do anything to divert its inevitability. This can be seen as a damning analysis of man’s inherent duality; the philosophic and intelligent may try to rationalise or ameliorate the aggressive anger of the more impassioned, but ultimately they perpetuate, and in many cases, end up enacting violence anyway. The means and route taken may be more convoluted but the bloody end is much the same; this is the lesson of man’s history.

Even more damning perhaps in its symbolic resonance is the moment during the rape scene when our eye is drawn to the figure of a man entering the tunnel, who sees the act taking place and yet walks away; a devastatingly simple yet effective condemnation of masculine cowardice and instinct for self-preservation.

By contrast, Alex is sophisticated, graceful and refined; eager, not for there to be animosity or recrimination between her past and present lovers but for them to get along on good terms. Of course, being introduced to her via the horrific attack, her subsequent words take on an additionally poignant texture. After play-fighting she tells Marcus, "I’m always the woman who decides", and on the train tries to explain to Pierre the secret to good sex as being independent of focusing on the other person’s pleasure – "you have to be selfish…if you focus on the other person’s pleasure you freeze".

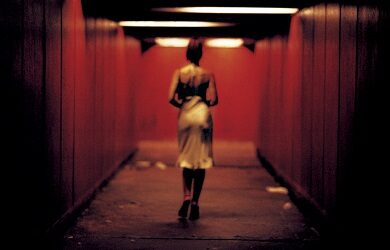

At the centre of the film is the scene which unsurprisingly generated a furore upon its release and led many to reactively condemn it as obscene. Alex enters the glowing red subway underpass, itself more than perhaps any other feature of the built environment so evocative of insecurity and implied threat, where she is assaulted in a scene lasting nine unbearable minutes.

From a stylistic point, the applied techniques are arresting in themselves, with Noe’s frenetic and disorienting camerawork settling completely still and unflinching for the duration, forcing you to experience the entire event shorn of any filmic manipulation or tropes. As a piece of direction then it is handled masterfully, with absolutely none of the purposefully difficult ambiguity of something like Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs, you are left simply with the unfolding horror of aggressive domination.

One of the key yet most difficult reasons to suggest that everyone should watch Irreversible is because of this scene. Firstly, because if we can contentedly stomach action-packed war or horror movies with all their glamorised death sluicing through our glazed minds, we should as part of a moral imperative be prepared to watch the representation of an act that is perpetrated in reality every single day.

Secondly, because it would render impotent the kind of adolescent ‘rape porn’ fantasies, and the ‘rape culture’ that is so worryingly prevalent among young males in today’s society, where the idea of enacting sexual violence on women is seen as a ‘soft crime’ or subject matter for laddish ‘banter’. Moreover, it might help in rendering inert the troublingly common instinctive response across society to lay implied blame at the feet of the victim, to believe that in some way ‘they had it coming’.

Essentially the rape-and-revenge narrative serves as a dramatic subtext for the real thematic exploration – the nature of time itself. The book that Alex refers to in the elevator, and that at the end we see her reading on the grass, is J.W. Dunne’s seminal 1927 text An Experiment with Time, which is something of a revelatory read.

Dunne was convinced that time was multidimensional and that in dreams our associational networks had the ability to explore our experiences in both the past and future time fields, giving rise in our waking life to sensations of déjà vu. He held that the universe was ‘stretched out in time and that the lopsided view we have of it – a view with the ‘future’ part unaccountably missing, cut off from the growing ‘past’ part by a travelling ‘present moment’ – was due to a purely mentally imposed barrier which exists only when we are awake. So that in reality the associational network stretches, not merely this way and that in Space, but also backwards and forwards in Time…’

On waking with Marcus, Alex sleepily recalls dreaming of a "long red tunnel" that breaks in two, but discards it as irrelevant as we have all involuntarily conditioned ourselves to do throughout our lives; limiting ourselves to one strictly linear progressive field of consciousness that can only be freed whilst in a dream-state.

Extrapolating on this then, one interpretation could be that all the events that take place are diffracted parts of a dream in the mind of the ‘higher’ observer, perhaps the version of Alex that we see at the end. It might even be the final scattered thoughts of a comatose Alex before her death..?

The quotation that opens and closes the film – ‘time destroys all things’ – can then be seen as appropriate regardless of whichever way we view time, forwards or back. The forward progression of time destroys all matter, degrades beauty and fades consciousness moment by moment. But so does the reversal of time, in that we see the object after we’ve seen its destruction, we see how the love and happiness of Alex and Marcus has been destroyed by irrevocable future events, symbolised by the shower curtain that hangs between them as they kiss.

(Alternatively, if you wanted to pursue the ‘condemnation of man’ theme, you could interpret the mantra as referencing the fact that time is a concept man invented to assign order to the world, ergo it is man that destroys everything; the world will continue regardless of time being conceptualised.)

Those thinking that the film, or this interpretation of it, is too depressing, can be reassured by the more hopeful way in which it tries to reconcile itself to the future. At the beginning of the film, two men whose identity is ambiguous speak of there being “no bad deeds, just deeds”, and “we have to go on fighting, go on living”; in itself almost an (im)moral code for man’s inherently destructive nature.

The men who approach Pierre and Marcus after Alex’s attack, tell them that “blood calls for revenge…vengeance is a human right”. And yet it could be said that the moral message of Irreversible is that this cycle of violence and retribution is doomed to ‘destroy all things’, no matter how natural the instinct for revenge may be.

With Irreversible, Gaspar Noe created a film that is still deeply troubling, traumatic and yet uplifting all at once. It is a film that whilst featuring perhaps one of the most distressing scenes between two people, also contains one of the most beautifully natural scenes of love between two people as well.

Whether it is, as has been speculated here, a feminist film, or a film condemning masculinity for all its undeniable flaws, it is an example of a film that pushes at numerous boundaries in the conceivable limitations of an art form and challenges the audience to reassess their own moral judgements, and for that reason it is a film that really should be seen by everyone

Michael’s blog can be read here