Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

An often beguiling film whose casual tinkerings with convention make for an extremely rewarding spectacle, Uncle Boonmee follows the last limping moments of a Thai farmer, Boonmee, as he stoically faces death from kidney failure. Hidden away deep in the jungle, the farmhouse he shares with his sister-in-law is bombarded with flies and spirits.

While eating dinner one evening, Boonmee is visited by the ghost of his dead wife, Huay. Their conversation is typical of the film’s sober, tentative tempo. Events and dialogue occur at a contemplative, sombre pace with the serene characters refreshingly devoid of the tendency for indulgent drama. This calm acceptance in the face of death and a haunting is strangely intriguing. The diners’ own measured actions are accentuated by the long, lingering shots that dig out every last detail and nuance from the scene.

As their sparse conversation draws on, Boonmee and Huay’s son Boonsong joins the table which, since they last met, has mated with a monkey ghost and turned into some form of hairy spectral creature. There’s clearly a trickling undercurrent of dry humour at play – a tea-party at which a ghost and a guy who looks like Teenwolf make up half the guests as the hosts carry on like normal is bizarrely funny (especially if you grew-up watching Rent-a-Ghost). Nothing of the film’s severity is lost through viewing it as humorous – the measured shots that link scenes together act like mood flatteners that mediate the changing course as the film moves onto another’s story. It transpires the reason for Huay’s visit carries a dark tinged promise of relief: sensing Boonmee’s illness she aims to persuade him to trek up to the cave, which was the birthplace of his first life, to die.

Alongside Boonmee’s drama with his unhinged deceased wife, the film follows various characters on their own stories that, for the most part, don’t seem to have much to do with any discernable main story. A princess makes an appearance and gets frisky with a catfish, the monkey-man reminisces about his love of photography and Boonmee’s home-help decides to become a monk. Each strand play out as tenuously related – if at all – micro-dramas. This does mean it’s often tryingly difficult to see where the film’s heading. Characters emerge but don’t seem to have a lasting impact.

Whereas commonly, emotion is used to boost the thrust of a narrative, the mini-stories in Uncle Boonmee, including his own tale, appear to drive towards building an ambience around the sense of isolation, community and fatalism with which the farmers live. The result is an overall structure that resembles a flowchart with no obvious resolution across any of its threads, yet whose loose ends add towards creating this unnervingly surreal atmosphere.

Even when focusing on one particular character there’s the feeling of being walked round a photography gallery – with various clues providing a rough link between the images you’re given. Yet everything about Uncle Boonmee stokes intrigue whether through its ambiguity, original story telling or charm.

Adrift

Adrift is an achingly sentimental saunter into the frivolity of love and jealously that tests the resilience of one adorable and seemingly stable family. Doting farther Mathias (Cassel) is a writer holidaying with his wife and children in some idyllic heaven on the coast of Búzios, Brazil.

Seen through the eyes of eldest daughter, Filipa, their picture perfect family shows signs of crumbling when she notices her father’s eyes constantly distracted by a young American lady living up the road. Though it’s evident for some time that the parents’ relationship is both sustained and weakened by hard boozing, the fourteen year-old Filipa isn’t as attuned to the subtle, underhand jibes the adults deliver one another. Refusing to accept her age as a limiting factor on her understanding of ‘adult’ subjects, she engages in a little detective work and uncovers evidence of her father’s infidelity. In an instant her perception of him is palpably different.

By showing the disintegrating relationship through the daughter, who herself is going through her own sexual awakening and learning something of the fickleness of young love, the film is able to cut through the intricacies and fine detail of the parents’ relationship which are shown to shrink in the significance of her own wants.

Where Adrift succeeds most is pairing Filipa first-hand learning experience – about herself, hanging out with her friends, exploring the allure and confusion of kissing boys, and making them kiss other boys – alongside her wavering perception of her parents’ ever more complicated relationship. By being neither totally naïve or enlightened, she learns to empathise with their situation – or at least not see them as unrecognisable aberrations.

Though the plot between the parents on occasion resembles a soap opera – smashed glasses, love-cheats and tears – as Filipa learns about herself, the parents mutate and change shape without ever altering their behaviour, making for touchingly entertaining viewing.

And with eyes matching the surrounding ocean in almost cartoonish fashion, like a French Adonis softened with age, Vincent Cassel is utterly convincing as adoring father and forgivable as committed philanderer.

Though the mother remains a bitter drunk to the cheating husband, as the story unfolds their back-story unravels elegantly around them. Despite all the high-drama, there are only teasers as to anything of any real threat taking place: stalling the speedboats, seedy holiday makers, a missing gun all juggle suspense with relief. Though this teasing with actual drama may only avow a lack of real action, it pays off movingly in its finale, verifying Adrift as well crafted and touching cinema.

Robinson in Ruins

Produced as part of the Landscape and Environment project organised by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Peter Keiller’s quasi-documentary plays like an enlightening lecture from a particularly knowledgeable academic whose years of scholastic pursuit and abstract thought have burnt away a capacity to converse in a linear manner. Like Keiller’s previous film Robinson in Space, Robinson in Ruins follows the ponderous adventures of the fictional Robinson as he sees wonderment in the banal and everyday sites that our eyes would otherwise glide over.

Vanessa Redgrave recounts the travels and meandering thoughts of our elusive hero on a range of subjects, inspired by the countryside he encounters, with a regal monotone that allows the playful prose to come to life, accentuating the oddity of his thought process. This is set against video footage of various sites, fields and road signs surrounding Oxfordshire. This might sound like daunting viewing, especially as it clocks in at 101 minutes and remains on the same pace for the duration, yet through the hero’s buoyant enthusiasm Robinson in Ruins is surprisingly entertaining.

Neither the director, narrator nor visual subject, Robinson himself holds an inscrutable position in the film, mentioned only as the observer and contemplator. Without the constraints (or indeed the benefit) of a visual depiction, the epiphenomenal form of Robinson has a ghostly presence that rises out of the wandering narrative as it shoots back and forth through time.

Imprisoned in the present through the ongoing drama of the renovation to the Gothic church, which acts as his shelter, the occasional word jars him out of this comfort. As early as the opening introduction we are told Robinson leaves jail looking for a place to “haunt” – poetic licence that provides the enigmatic wanderer a passport to vacillate his seat in time.

When his thoughts cross through time, the spectral figure of Robinson somehow fixes the narrative more firmly, as if he were time-travelling with the narration.

Robinson’s strands of investigation dart off and frequently criss-cross over each other with lively vigour, as when he connects the developmental policies of supermarket LIDL to the ideas of later Heidegger via a digression on German farmers. Much of the filming took place in 2008 at the height of economic panic, so Marxist theory is shoehorned in to a number of topics – seeing how he makes the step from Marx’s notes on Epicurean philosophy to David Kelly’s suicide then back over to Adorno with light-footed finesse is typically enjoyable.

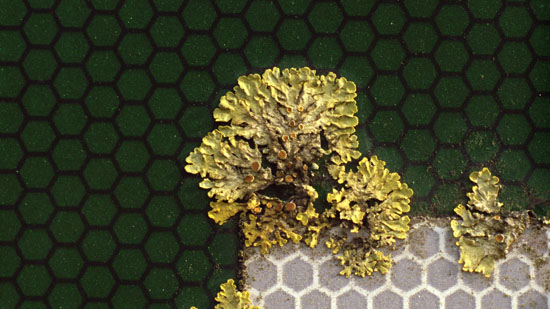

Robinson In Ruins is a delightful oddity that floats outside the usual bounds of genre. Though the subjects crossed in the film skip from expansive to the banal to the otherwise dull, it does so in a voice of unique wit that instills these topics with the same wonderment and curiosity as Robinson has for them. Any films that leaves you wanting to grab the nearest book that can furnish you with a greater understanding of the colonisation patterns of lichen is a rare find.