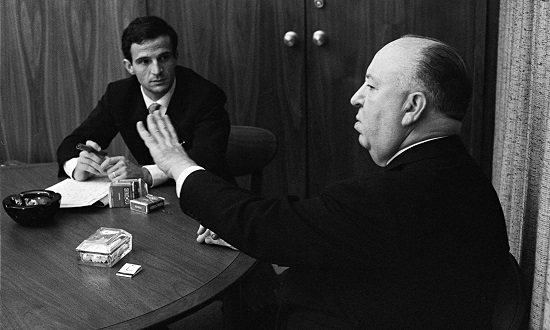

In 1962 the accomplished French New Wave director and film critic Francois Truffaut wrote a letter to Alfred Hitchcock. In it he requested an extended interview of 500 questions to run over the course of a week and to be recorded on tape. Hitchcock eagerly accepted and in August of that year the pair met in Hollywood for a week long discussion of every single one of Hitchcock’s films.

What followed has been heralded as one of the most important encounters in the history of cinema. The book of the interviews was published four years later in France and five years later in America under the original title of Hitchcock. It has since been cherished as a rare moment where the secrets of film were prised from the great Buddha of suspense by one of his most dedicated followers. A textbook explanation of the mechanics of eliciting emotion from the editing together of moving images.

The French avant-garde idea of "pure cinema" is key to much of the discussion, with Hitchcock and Truffaut discussing how the best, or most "pure", films should use the camera and sound design to tell a story. They lament the passing of the silent film era as this was "the purest form of cinema", according to Hitchcock, since it "told the story in a cinematic way, through a succession of shots", as opposed to "photographs of people talking". Rear Window was "a purely cinematic film" because it is entirely about the act of watching in that "you have an immobilized man looking out…The second part shows what he sees and the third part shows how he reacts."

As a result of the near mythical status that the interviews took on, their importance has been overblown and the more cynical back story of how the interviews were used as a crude marketing tool is rarely told. Rather than being a great meeting of minds indulging in Kuleshov and Murnau between lunches and witticisms, the whole thing was in fact probably one of the most successful publicity campaigns of the 20th century.

Truffaut was very open about this. In his invitation letter he explained his motive for wanting to conduct the interviews: "the propaganda we initiated in the Cahiers Du Cinéma, while effective in France, carried no weight in America because the arguments were over-intellectual." In the pages of the prominent French film journal referred to, Cahiers Du Cinéma, Truffaut and others had long argued that Alfred Hitchcock was a great artist and not merely a director of popular thrillers. He passionately believed that Hitchcock was a superb ‘realist’, in the sense that he was able to capture emotions and project them onto a screen creating sensations which felt genuinely and completely real.

This wasn’t a view shared by many elsewhere in Europe and America. Influential British critics like Penelope Houston and Lindsay Anderson at Sight & Sound were dismissive of Hitchcock’s artistry, not least because of his enormous mainstream popularity. Whilst he was enthusiastic about the popularity of his films, this dismissal of them as being somewhat low-brow hurt Hitchcock and was something he was keen to remedy.

Robert Kapsis points out in Hitchcock: The Making Of A Reputation that the polishing and upkeep of his public image had been a constant concern throughout Hitchcock’s entire career. In 1927, after the success of his first hit, The Lodger, he had his famous profile sketch printed onto small wooden jigsaw pieces, packaged into bags and sent to family, friends and influential industry people. As if having his own personal logo wasn’t enough, Hitchcock felt the need to literally post it through people’s doors – and he was only 28.

Some 35 years later Hitchcock needed to harness this spirit of self-promotion more than ever. Whilst his mainstream reputation was soaring high following several years of the popular TV show Alfred Hitchcock Presents, his critical reputation among serious critics was in danger of stagnating just as The Birds was due to be released. The timing was therefore perfect when one of France’s foremost critics came forward to offer him an extensive platform from which he could plug his new film under his revised guise of Hitchcock The Artist.

When you compare the book to the original interview tapes it becomes pretty clear quite how much of a propaganda tool Hitchcock really was. The size of the book compared to the fact that Truffaut claimed to have gathered 50 hours of conversation shows pretty plainly the extent to which it was edited over the course of four years. There was a constant, and increasingly fraught, back and forth between Truffaut and his translator Helen Scott frantically editing and revising, with Hitchcock himself having oversight over drafts and the final editions.

Truffaut’s editing was crucial to the shape of the finished book, after all it wasn’t just Hitchcock who wanted the campaign to succeed. As an early flag-waver for the auteur theory, and with Jules Et Jim having just be released and The Soft Skin on its way, Truffaut himself had a lot to gain from the interview’s popular success.

He didn’t just edit out linguistic blips and stumbles in speech, which make Hitchcock sound considerably more confident and precise, but he edited meaning too. He wanted to make sure that the occasionally clunky, meandering conversation flowed in a direction of his choosing and so removed whole swathes of the interview. For example, sections discussing the film industry are absent from the text, changing the focus to be less about Hitchcock himself and more about Truffaut’s vision of Hitchcock the artistically minded auteur. Hitchcock was often more concerned with the practicalities and production details of his films than the romantic philosophical notions behind them, and this could frustrate the French critics.

The collected writings of Hitchcock in Sidney Gottlieb’s Hitchcock On Hitchcock provide a far more believable portrait of a director who, inevitably after half a century of making films, changes his mind and contradicts himself on occasion. A man less coherent and profound but probably more convincing than Truffaut’s omniscient creation.

Not that any of these pernickety details surrounding accuracy and truth got in the way of a great PR coup, of course. The book was a great success after its eventual publication in both English and French in 1967. It contributed to the elevation of Hitchcock’s image from the creator of popular but shallow hits to a profound artist who controlled every element of his films.

The film critic Philip French said in an interview that he was more or less laughed out of the room when he suggested to a senior editor of Time magazine that they do a cover story on Hitchcock in 1965. But a year later critics were queuing up to lavish praise on the brooding auteur. Motion Picture Exhibitor proclaimed in 1969 that where his films used to attract shoot-em-up audiences, "now a Hitchcock film is considered a work of art… on the rarefied plane of a Stravinsky symphony or a Picasso painting."

Such enthusiastic talk of rarefied planes was building in the 1950s and 1960s anyway, with others aside from Truffaut calling for Hitchcock to be considered more deeply. Fellow Cahiers critics Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol published the first book length study of Hitchcock in 1957 and in 1965 Robin Wood famously asked in Hitchcock’s Films: "Why should we take Hitchcock seriously?" By the late 1960s their auteurist perspective on film had become a popular method of analysis for non-academic film critics. In other words, they had created the perfect environment for the publication of Hitchcock and the blossoming of the idea of Hitchcock as artist.

Ironically, these seeds planted by Chabrol, Rohmer, Truffaut and Wood in essentially wanting Hitchcock’s films to be looked at more deeply, has since led to such a glut of critical thinking around the director that the films themselves have almost become a means to the end of critical noodling. Even before Hitchcock died in 1980, over 540 books and academic articles had been written on him. John Belton made this point in Cineaste in 2003, and, in an ironic play on Robin Wood’s bold question from 1965, felt it was time to ask: "Can Hitchcock be saved from Hitchcock studies?"

It feels fitting, therefore, that 50 years on from the book’s publication, and as academia threatens to drain the emotion from Hitchcock’s films, Kent Jones’ documentary Hitchcock/Truffaut should bring together some of greatest directors of today to rekindle the original lust for cinema. Despite its many holes in terms of being a completely safe source for understanding Alfred Hitchcock, the exchange between Truffaut and The Master of Suspense in 1962 still remains an utterly engrossing dive into the meanings and mechanics of cinema. A good time to return to the myth, perhaps.

Hitchcock/Truffaut is in selected cinemas now

Louie Freeman can be found on twitter at @louief_b