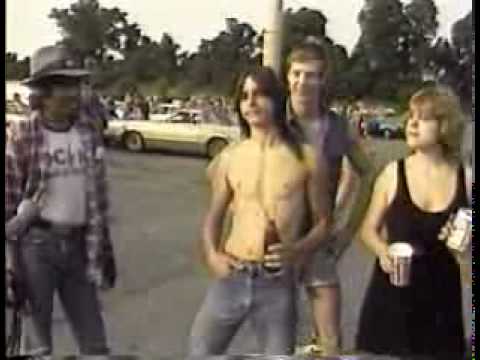

Thirty years ago next month, a 16-minute, no-budget documentary titled Heavy Metal Parking Lot immortalised – warts, bum fluff and all – a wasted sea of American teenagers in the lawless no-mans-land of a Largo, Maryland parking lot. Filmed by unknown filmmaker duo Jeff Krulik and John Heyn in the hours leading up to a Judas Priest and Dokken arena show, it captured untold shirtless bros, poodle-haired chicks and veteran hangers-on in the fuzzy throes of pre-Priest abandon, united in their limitless love of partying, heavy metal and the crudest of homemade ephemera.

While on first glance it may just seem a shittier, more spandex-heavy Woodstock, Heavy Metal Parking Lot inadvertently eternalised the everyday workings of a cresting subculture, offering future times an anthropological document bursting with no-fucks-given heart. Having become an underground cult classic by the early 1990s – usually traded on bootleg VHS and reportedly a favourite on the Nirvana tour bus – Krulik and Heyn’s film puts metal’s vital cog of community firmly centre-stage, with only a fleeting closing minute set aside for Halford and co.’s performance. Indeed, despite becoming little more than a cinematic spit in the ocean (its first known theatrical showing outside of Washington, D.C. was in 1997) Parking Lot remains one of the genre’s most definitive and downright endearing records. Filmed one Saturday afternoon in 1986 with equipment borrowed from Krulik’s day job at a local public access station, it’s a primitive yet quintessential indie film gem that has, over the last three decades, steadily become an enduring snapshot of heavy metal and its mores of the time.

In early March, two years before Krulik and Heyn set off in the direction of that Largo parking lot with “no plan, no agenda”, Rob Reiner’s rockumentary par excellence This Is Spinal Tap was released to a lukewarm response. Made on a tidy $2 million budget (read: exactly $2 million more than Heavy Metal Parking Lot) Tap would, of course, soon be regarded as one of the finest sendups of the decade, its exacting lampoon of rock n’ roll excess fully realised via Reiner’s cinéma vérité-style mastery. Whilst both conceptual and commercial worlds apart, Spinal Tap and Parking Lot operated within the very same sphere of niche subcultural ritual and peak parody – a fact all the more illuminated with the luxury of hindsight. Just two cases in point: take the guy wearing a zebra-striped Spandex outfit, drunkenly ranting against punk and Madonna or the dude who introduces himself as "Graham… as in gram of dope". These are actually “characters” in Parking Lot – real-life Nigel Tufnels – vicariously operating on the other side of the malfunctioning pod. With the advent of Guns N’ Roses, Headbangers Ball and the predestined factionalizing of the genre peering around the corner, Spinal Tap and Parking Lot distilled the drollest, most unrestrained quirks of mid-Eighties metal culture.

But, of course, metal was then and is now a considerable matter more than mere loaded, leather-clad longhairs worshipping at the altar of vainglorious luminaries, something that many stellar documentaries far beyond the professional drought of Parking Lot and the hyper-hagiographic lampoon of Spinal Tap firmly attest to. Here’s just eight of the best worthy of your immediate attention.

The Decline of Western Civilization II: The Metal Years (Penelope Spheeris, 1988)

There’s a scene in Penelope Spheeris’ pioneering The Decline of Western Civilization II: The Metal Years in which W.A.S.P. guitarist Chris Holmes is seen vacantly guzzling a fifth of vodka whilst lounging in his pool. Rendered so fucked he was – in his own words since – totally incapable of speech, it serves as a brief yet no less stark distillation of the blind excess that was commonplace in the Los Angeles scene circa ‘86-88. The second instalment in the documentarian’s trilogy tracing punk rock, heavy metal and gutter punk respectively, The Metal Years candidly enshrined an age where the dudes did wear more make-up than the girls and the singer’s voice (yes, even Vince Neil’s) was every bit as solid live as it was on cassette. Featuring Cooper, Ozzy, Poison, Aerosmith, Kiss, Motörhead and more, it remains, 28 years later, a definitive portrait of the scene, one whose main players’ communal credo of God-given personal infallibility is plainly and watchably askew throughout.

Some Kind of Monster (Joe Berlinger & Bruce Sinofsky, 2004)

“Frantic tick tick tick tick tick tock.”

To this day I genuinely struggle to accept someone – an actual human person – thought, “Yeah, I’m pretty happy with that. I’m going to roll with that one.” Somehow, beyond everything else, the chorus to ‘Frantic’ is, for me, totally microcosmic of the crushing stasis Metallica found themselves in whilst writing and recording 75-minute misfire St. Anger. But, as the saying goes, where there’s muck there’s brass… and where there’s brass there’s probably a petulant, peroxide-haired Lars Ulrich peacocking like Robbie Williams circa 1995 sans the slightest sliver of magnanimity. Anyway, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s Some Kind of Monster is an exceptional film and classic metal doc for many reasons, not least for demythologising a band collectively clawing at the ceiling of personal and shared disarray. And lest we forget the sheer decency of Kirk Hammett throughout. The man has the patience of a saint.

Such Hawks, Such Hounds (Jessica Hundley & John Srebalus, 2008)

"Sometimes you just want to play the same riff over and over again for 52 minutes.”

If the above quote from Such Hawks, Such Hounds: Scenes From The American Hard Rock Underground resonates with you – no matter how vaguely – we can most certainly be friends. Documenting various strands of U.S. sludge, doom, psych and stoner rock from the ’70s to the present day, Jessica Hundley and John Srebalus comprehensively plunder sonic lineages from the likes of Pentagram, Mountain and Sir Lord Baltimore to modern torchbearers including Sleep, Saint Vitus and Sunn O))), who are extensively interviewed throughout. Much less concerned with the realm of headbanging and throwing devil horns in favour of seeking out crushing weight and cosmic exploration, a distinction in favour of "heavy hard rock" over "heavy metal" is made throughout the film yet the crossover continuum between both genres (and their various sub-genres) is so rampant the film really benefits from the confab.

Lemmy (Greg Olliver & Wes Orshoski, 2010)

Loath as I am to admit it, it wasn’t until I devoured his 2003 autobiography White Line Fever that I fully grasped the towering wit and immeasurable wisdom of metal’s ultimate incarnation, the sorely missed Ian Fraser “Lemmy” Kilmister. Released 7 years after said protracted yarn, Greg Olliver and Wes Orshoski’s Lemmy (subtitled "49% motherf**ker. 51% son of a bitch") is a thorough account that strikes a keen balance between dredging up tales of our Lord and saviour’s wildest excursions of yore with his supremely no bullshit, present-day cogitations. While Lemmy’s musical legacy and clout will forever prosper with each passing year, Lemmy, the film, paints a picture of a man who, still thriving beyond the more decadent dealings of his heyday, reveals himself to be a gentle, considerate and perfectly human soul worthy of our respect.

Until The Light Takes Us (Aaron Aites & Audrey Ewell, 2008)

One of the genre’s most notorious subcultures, the Norwegian black metal scene of the early ’90s is certainly not without its arcane narrative. Revisiting the flurry of suicides, murders and church burnings that ran parallel with its second wave circa 1990-1992, Aaron Aites and Audrey Ewell’s Until The Light Takes Us delves into said darkness by way of the likes of Mayhem, Immortal and Darkthrone, whose founder Gylve ‘Fenriz’ Nagell acts as a key –albeit fairly reticent – protagonist alongside Mayhem and Burzum’s self-styled pagan scholar Varg ‘Count Grishnackh’ Vikernes throughout. Whilst far from the most critically-acclaimed of the bunch here, a small wealth of archive footage and a patient filmmaking eye makes for a fascinating closer look at a largely misunderstood cultural terminus that, viewed from the safe distance of the modern day, feels a tad hollow and hyperbolic.

Anvil! The Story of Anvil (Sacha Gervasi, 2008)

Most of us know an Anvil. Many of us have been in an Anvil. If you neither know nor have been in an Anvil, please accept my sincerest sympathies. Fighting the corner for every band that have played more shitty, unpaid, empty, thankless shows than any less-than-shitty band deserves, Anvil! The Story of Anvil is the purest amalgam of the ancient myth of Sisyphus and This Is Spinal Tap. Whilst the discrepancy between metal documentary and mockumentary is now throwaway, Anvil blurred the lines best by successfully positing four burnt-out Canadian nonentities as metal’s most endearing embodiment of resilience, spirit and self-belief in the face of the overwhelming odds stacked against them. Whether due to the innately fragile nature of watching it at the tail-end of a messy party several moons ago, it sure made a sizable impression on your writer on first viewing. “Man, I totally want to be these guys when I grow up,” I professed, clenching my fist. Once the Buckfast wore off, I really didn’t. Still – sizable impression all the same.

Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey (Sam Dunn, Scott McFadyen 2005)

Doubling up as easily the most kickass hat tip in rock doc history, filmmaker and anthropologist Sam Dunn’s Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey begins with a little footage from the holiest, most independent of grails (Heavy Metal Parking Lot, need you ask?) paired with the oracular opening mantra of Maiden’s ‘Number of the Beast’. An opening gambit that rightly postulates 1986 as the apex of heavy metal’s upswing, it perfectly introduces Dunn’s comprehensive retrospective of metal’s classical, compositional roots in Wagner, its embryonic form in Blue Cheer and its unprecedented rise from the ’70s onwards. A self-confessed metalhead, Dunn’s exploration as to why the genre has always evoked such polar reactions is masterfully bolstered by splicing a host of with-it musicologists and sociologists back-to-back with exclusive interviews with metal royalty, including Tony Iommi and Bruce Dickinson. Comprehensive and quasi-academic without ever feeling overbearing, Journey is a documentary delivered with such tangible passion that it ensures Dunn’s proud and painstaking defence remains unmatched.

Get Thrashed: The Story of Thrash Metal (Rick Ernst, 2006)

"It was the touch of God, man. It was like, I am seeing something that only a few people really understand. To a lot of other people it was just a show but for us it was just like bowing at the altar.”

The simple yet totally on-point words of Corey Taylor in (and the clear-cut message of) Rick Ernst’s thrash metal doc Get Thrashed. Side-tracking musicology and the kind of enquiring, anthropological nuance that lends to Sam Dunn’s Journey, Ernst’s film is a linear, brilliantly edited exposition told by the artists that lived it. Thanks to an extraordinary abundance of archive footage of innumerable moshpits and interviews with its main (and not-so-main) players, this is the ultimate story of thrash’s reclaiming of metal from pop, from its rabid stirrings in the Los Angeles, Bay Area and New York scenes, right up until its commercial peak and beyond. Delving far deeper than the Big Four of ‘tallica, Slayer, Megadeth and Anthrax, you’d be hard-pressed finding a more far-reaching, chronological look at any modern sub-genre, never mind one bowing at the altar of most glorious thrash.

Pre-emptive disclaimer: honourable mentions must be extended to Sam Dunn’s Global Metal, Adrian Winkler’s wonderfully revelatory Celtic Frost documentary A Dying God and Iron Maiden: Flight 666 co-directed by Scot McFadyen and Sam Dunn.