“I’m the wrong kind of person to be… really big and famous,” states Elliott Smith in an interview with a Dutch television show which appears in Heaven Adores You, a new documentary exploring the life and work of the singer.

It is a sentiment shared by many of the figures interviewed in the film. In one of its most outright moving scenes, his friend and former publicist Dorien Garry recalls a late-night email she received from the singer while he was on tour. In the message, he warned her not to be surprised should “something happen” to him. An overwhelmed young woman at the time, the memory is clearly still a difficult one for Garry, who struggles to maintain composure while relaying it to camera.

Given his death in 2003 – a death that has yet to be officially deemed a suicide – any film about Elliott Smith is, in some respects, going to be a tough one. Directed by Nickolas Rossi, Heaven Adores You gathers over 30 of the singer’s friends and colleagues to talk about the man and his career, but it still feels vague and incomplete. Those interviewed all formed a big part of Smith’s life – as bandmates, friends, even his sister – and the shading they provide his character is welcome and occasionally revealing. But the film’s reverential tone means that while it doesn’t exactly back away from the darker aspects of Smith’s story – those self-destructive tendencies Garry speaks of; the various addictions that plagued him toward the end – it doesn’t exactly shed any light on them, either.

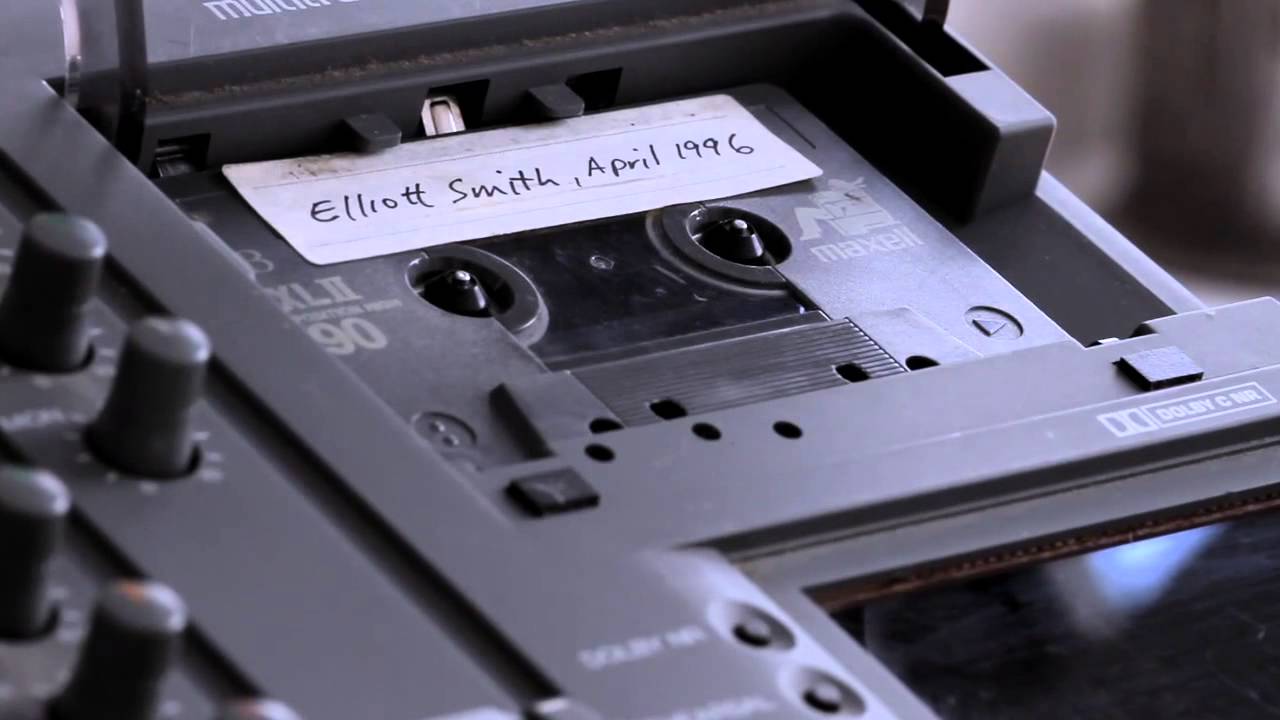

Of course, nobody was looking for a sensationalist take on the singer. The central flaw of Heaven Adores You is that longtime fans will leave it without having learned anything new, and certainly not anything they hadn’t already inferred. The archival interviews with Smith himself, in which he meanders patiently and thoughtfully through the questions asked of him, are arguably its highlights. More of them would have been welcome.

But there are some fascinating moments here all the same. The film takes his unlikely appearance at the Oscars in 1998 as its initial framing reference (“Kind of a kick in its way… Wouldn’t want to do it again,” he says), but soon doubles back further, all the way to his childhood. The various photos of him in his infancy through to his teens – all winning grin and baggy t-shirts – are wonderfully poignant things, though the hostile relationship he endured with his stepfather isn’t given a great deal of weight here. Surprising, given the impact it made on several songs early in his solo career.

Heaven Adores You soon eases into a chronological style, detailing Smith’s earliest musical projects with classmates in Texas and then in Portland, Oregon, a city he moved to at the age of 14 and one where he would spend much of his life. By the time it reaches the dissolution of Heatmiser and 1997’s Either/Or, Smith’s one-time girlfriend, musician and sound engineer Joanna Bolme (who would go on to co-produce his posthumous From A Basement On The Hill) reminisces about the singer and his song ‘Say Yes’, pointedly stating that while it is a beautiful song (one written about her), the circumstances surrounding it were far from ideal. Bolme goes on to mention Smith’s “turning” on those who had once supported him by calling them out in his lyrics. It’s a fleeting reference to a more vindictive side of the singer that is only rarely touched on here; indeed, it’s all but forgotten as soon as she speaks of it.

Over a running time of 104 minutes, Heaven Adores You succeeds in painting a picture of a sensitive, punky kid who grew into a troubled genius much loved by those around him. It deserves plaudits for this, as it does for its sensitive use of Smith’s music, often deployed over some striking footage of Portland, a city that he eventually left for New York and then Los Angeles, yet one that certainly influenced him greatly. It’s funny in places, too – L.A. club owner Mark Flanagan’s frank contributions tease lightness out of some grim subject matter, as do those of musician and producer, Jon Brion, who features alongside him. ‘I Love My Room’, an endearing composition from the singer’s teenage years, also makes a couple of smile-inducing appearances.

So, to criticise a film that seems to intentionally steer clear of much of the sadness present in Elliott Smith’s story for doing exactly that isn’t, perhaps, entirely fair – and in its defence, sadness isn’t all there was to Smith’s life. Heaven Adores You has a whole lot going for it. As an affectionate overview of and introduction to the singer and his music – and at the festival screening where I saw it there were plenty in the audience unfamiliar with the man – it works very well, and fans will surely enjoy its first half, in particular. But by skimming over certain aspects of Smith’s life, it’s hard not to consider it a missed opportunity. Something that could have been definitive is instead just decent; something that could have been unmissable is only worth seeing.

Heaven Adores You is released in the UK on the 17th of November