My first exposure to Nine Inch Nails was at a tame American school dance when I just barely qualified as a teen. The venue was the school gymnasium and the DJ was our gormless gym teacher, who had foolishly asked students to contribute CDs to the musical selection. It was mostly awkward slow dances with the girls (who at that age towered over us) to awful ’80s ballads, slow jamz and the occasional neutered grunge track. Then someone slipped in a radio edit of ‘Closer’ on a burned CD, which was played to much hysteria until the teacher realised we were all chanting the missing phrase “fuck you like an animal” and the song was unceremoniously pulled.

‘Closer’ represented a strange moment in time when industrial music finally broke, to the extent it ever would. Even high school jocks claimed to own The Downward Spiral. For myself the song pointed the way down a long path back through Ministry and KMFDM to Coil, TG and Cabaret Voltaire. But unfortunately ‘Closer’ lingered in the pop culture doorway too long and let in the worst kind of adolescent nu-metal sludge and whining pseudo-goth emo – all of which lacked the one thing that made ‘Closer’ so potentially dangerous – its sexiness. Despite Reznor’s often misogynistic lyrics (“I got a big gun” uh geddit Bevis?) and references to sexual violence, what was interesting about The Downward Spiral was the occasional traces of homoeroticism or S&M – almost like an MTV-safe name check to the gay, queer and ambiguous strands of EBM and industrial (DAF, Coil, certain aspects of Wax Trax!, etc).

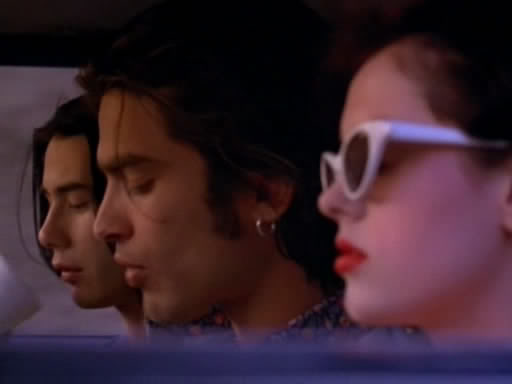

Gregg Araki’s 1995 film The Doom Generation, part of his Teen Apocalypse Trilogy, is in many ways a tribute to Nine Inch Nails (it opens with ‘Heresy’ blasting in a club) and the dark side of mid-’90s pop culture. Amy Blue (Rose McGowan) and Jordan White (James Duval) are a couple of stereotypical industrial/goth teens who pick up a stranger, Xavier Red (Johnathon Schaech), who leads them on an increasingly surreal and murderous roadtrip. After accidentally killing a convenience store clerk, with great schlocky special effects, the trio flee in Amy’s jalopy, at every horrible pit-stop encountering strangers who claim to have been dumped by Amy and join in the cross-country pursuit. Along the way, the three-way sexual tension escalates leading to much bed swapping and ultimately a threesome.

Re-watching the film now is a lot like re-listening to The Downward Spiral: both are dated, trashy and full of awkward sentiments, yet both are exhilaratingly experimental and (for better or worse) genuinely transgressive in their treatment of sexual themes. But The Doom Generation goes much further in subverting the hetero-normative grunge model of masculinity – though for Araki, a pioneer of New Queer Cinema, this was his most heterosexual film.

To this day, The Doom Generation still seems to divide critics. For fans of B-movies and horror, it was a bit too pretentious and arty. For others it was a failed art film, too loose and shambolic to achieve its goals. For cineastes who prize things like ‘plot points’ and ‘character development’, it simply didn’t compute. But for fans of similarly perverse mixes of high and low culture, and reckless genre mashups, it’s an absolute masterpiece.

Roger Ebert famously gave it zero stars, framing it as a lesser version of the similarly stylized and themed Natural Born Killers the previous year. For Ebert, the problem was that the characters were too disaffected and unlikeable and the film failed to moralize about the copious murders, with Araki’s own views cloaked in irony and artifice. If you think The Doom Generation is actually about teen lovers on a killing spree then it will never be as substantial as say, Badlands. But once you realise it’s a movie about being a teen, it all makes perfect sense. For a hormonally charged adolescent, there’s no middle ground: everything is either eye-wateringly boring or a matter of life and death. Everyone is against you and out to get you and no one understands. A post-Cobain musical landscape might as well be the actually post-apocalyptic landscape in which our protagonists find themselves. The Doom Generation makes flesh these myopic teen fantasies with hilarious results.

It’s the excellent art direction – something between Dario Argento, Alex Cox and John Waters – which really sells this nightmare view of America: a strange nether world of fast food joints and abandoned buildings. Everything from the low budget gore to the extremely silly motel décor was clearly done on the cheap and yet somehow brilliantly photographed and lit. The nearly constant cameos (Perry Farrell, Heidi Fleiss, Tom from The Brady Bunch to name just a few) contribute to the general strangeness and overwhelming sense of déjà vu.

In this teen’s eye view of America, the blasé attitude of the three, who care more about getting laid than the murders they commit, is exactly the point – a cutting satire of 1990s ennui. Seeing Araki regular James Duval doing his best Bill And Ted impression, pseudo philosophising and wrestling with his sexuality, while everyone from the FBI to neo-Nazis are in pursuit, is a hysterical contrast. But in one of the film’s actually poignant moments, a break from all the surface, the group shed more tears when they run over a dog with their car than for all the murders combined.

The three characters aren’t underdeveloped, they’re just hiding behind a very teenage wall of detachment and aloofness – with moments of weakness and insecurity occasionally showing through – like the occasional pauses in Amy’s barrage of obscenity: "Eat My Fuck". Their complex relationship is not sold on the sometimes incredulous dialogue or acting but on the very palpable chemistry between the three. Among all the surrealism and pop culture tropes, it’s the actual sex scenes which are most realistic. The sex is awkward, sometimes embarrassing and surprisingly graphic: Johnathon Schaech licking come off his fingers still has the power to shock. The Doom Generation makes a three-way dynamic actually believable, which in the history of film is no easy task (with the notable exception of Alfonso Cuarón’s 2001 picture Y Tu Mamá También, another road movie).

Whether you actually find the characters likeable depends a lot on what kind of teen you were. If you were a popular, athletic type for whom high school was the best years of your life, then this film is not for you. But if you spent your young adulthood being bored and full of disdain for the wasteland of American (or British) popular culture, you’ll probably find the trio’s inarticulate rage and blatant narcisism strangely endearing. The ’90s were shit and I’m not sure I trust anyone who wasn’t a bit disaffected then.

Much of the shock of the The Doom Generation has been tempered by time. If you want more provocative combinations of cartoon violence and sex then try Otto; Or Up With Dead People (2008) or anything else by Bruce LaBruce. But much like ‘Closer’, Araki’s film is a celebration of ‘deviant’ sex in a seductively populist package and in that way still feels a bit dangerous.

The Doom Generation is released on DVD by Second Sight Films.