Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas was released at the cinema in 1990. A quarter of a century later and it’s muscled its way into every corner of the culture, endlessly quoted, endlessly imitated and endlessly parodied. It opened up completely new territory in the gangster genre, so much so that any such film to come along since has had to pay the artistic equivalent of a Sicilian tribute. It’s impossible to imagine the likes of Pulp Fiction, Donnie Brasco, 25th Hour, American Gangster and Gomorrah (to name a few) existing in the form they do without it. That’s even before we get to TV series’ like The Sopranos or Breaking Bad.

Yet in many ways, Goodfellas is a conventional rise and fall narrative, familiar from gangster films going all the way back to the likes of Underworld, The Public Enemy and Scarface, made during America’s Roaring Twenties and Depression Era Thirties. This backdrop of boom and bust tends to dictate the kind of gangsters we get in the movies. In boom times they’re ruthless social climbers, heavy on the conspicuous consumption, while in busts they’re often tragic figures, anti-heroes with a line on realpolitik, battling a System far more rotten than they are – Killing Them Softly being an obvious recent example.

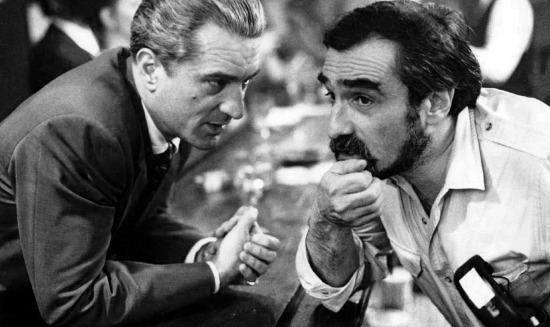

After Mean Streets, Scorsese saw no point in making another gangster film unless it provided something new, and for him that meant it had to be close to the spirit of documentary. In Nicholas Pileggi’s book Wiseguy, about the life and times of Henry Hill, a foot soldier in the mafia, he found the perfect material to adapt in this way. “I knew it would make a fascinating film if we could keep the way of life in the book,” said Scorsese. “To be as close to the truth as possible in a fiction film, without whitewashing the characters or creating a phony sympathy for them.” Goodfellas exploits many of the formal techniques of documentary, like voice-over narration, captions and intertitles, real locations and events, even real wiseguys roped in as extras. Most importantly, Scorsese grew up in the kind of neighbourhood he depicts – his portrait of his parents in the 1974 documentary Italianamerican is rich in the kind of ethnic idiosyncrasies found in the film. We might be watching the story of Henry Hill, but in the everyday details and atmosphere, we’re getting a veiled biopic of Scorsese himself.

The biopic element contributes a youthful nostalgia to the first act of Goodfellas, despite the violence that punctuates much of it. The early scenes look like something out of an Edward Hopper painting or a film by Elia Kazan, a melancholic, buttery light coming from street lamps and tenement windows. The canary yellows and lime greens of the wiseguys’ Dandyish attire have a Technicolor saturation to them, as do the cherry reds of lipstick and night blue of eye shadow, or the shimmering, streamlined chrome of the Cadillacs and Oldsmobiles.

The first hour is dominated by the seduction of the lifestyle of a gangster, nowhere more so than in the intricately choreographed steadycam shot where Henry takes Karen to the Copacabana, escorting her through a labyrinthine series of corridors and kitchens, all the way to a table right at the front of the stage. “We were like movie stars with muscle,” he says towards the end of the film, and in the Copacabana scene we’re seduced by that idea as much as Karen is by him, revelling in the power of celebrity (or in this case the celebrity of power), where every door is opened for you, every cigarette comes lackey-lit and every drink is on the house.

The music is pushing nostalgic buttons too, but then the music in Goodfellas – its effect on narrative, shot composition and dialogue – probably deserves a whole article in itself. A significant chunk of the budget was sunk into securing exactly the tracks Scorsese wanted, some of which he knew years before shooting, others decided in the editing room during post-production. The only rule was that the music in any scene had to be from the period of that scene or earlier. Cream’s ‘Sunshine Of Your Love’ couldn’t be used for the sequences in the 1950s for example. Perhaps more than any other film I know, Goodfellas itself is like a classic album. You can finish it, go back to the start, drop the needle and take it in all over again, never growing tired of it, feeling your way further into its vibe.

Frequently, of course, that vibe went bad. The viciousness of the opening scene is a kind of astringent in this respect, Scorsese making it clear right off the bat that whatever else these men might be, they are ruthless murderers. Then, just when we’re putting that behind us and getting comfortable riding along with Henry, we get the ‘funny how?’ scene, famously improvised and based on an actual experience Joe Pesci was subjected to by a local wiseguy – like Scorsese, he grew up in this world too. “Either Henry’s gonna get killed or he’s gonna get hugged,” says Scorsese. “He has to call Tommy on it. It’s intrinsic to their way of life, that scene.” This is how their mettle and their loyalty are constantly being tested. It’s also all about ‘performance’, the poker-faced quality of their front. In this world you have to learn how to act, but it’s like acting on a tightrope – fluff your lines and you might end up with an ice pick through your neck.

Still, we remain complicit with the violence that goes along with the lifestyle up to this point, emulating Henry’s nonchalance. We rationalise its escalation, whether it’s the mailman’s head stuck in the oven, the pistol whipping on the driveway, strangulation by telephone wire, or even the murder of Billy Batts after Tommy blatantly refuses to go and get his shinebox.

With the shooting of Spider, this dramatically changes. Having put ourselves in the shoes of these characters for just over an hour or so, we’re suddenly confronted with the character in whose shoes we probably belong, and they’re shoes being shot at. Like the ‘funny how?’ scene, Spider’s murder reveals how, in this world, glamour can switch to brutality in the twitch of an eye. It was the only scene Warner Brothers tried to get cut. Apparently, some members of the preview audience became so incensed by it they were threatening to become violent themselves. There’s the obvious shock in its senselessness, but I can’t help thinking there’s a subconscious awareness that we’re paying witness to our own powerlessness here, and this is what really drove people crazy.

Not that there’s much chance to contemplate any of this at the time, because things continue to move at a breakneck pace. Scorsese always wanted Goodfellas to be a fast movie, “like a two-and-a-half-hour trailer”, but by the time we hear the opening bars to Harry Nilsson’s ‘Jump Into The Fire’, which starts the ‘last day of a wiseguy’ sequence, things are spinning faster than the blades of the helicopter following him. Henry’s cocaine use becomes the visual cue for fast edits, jump cuts, skewed angles and clipped riffs from a dozen different songs, all combining to capture his palpitating and paranoid state, unable to prioritise between offloading guns in the trunk of his car, prepping a drugs mule, and making tomato sauce.

No one really does drugs in films quite like Scorsese because no one really did drugs quite like Scorsese in real life. He knows them from the inside and the outside, well-versed in both the highs and lows of addiction. Drugs lead the way to a broader theme in his work, and a pervasive one, namely excess itself, whether it’s an excess of drugs, consumerism, murder or money. With cocaine, the desire for the drug becomes, in essence, the desire for more desire. An avalanche of the stuff is never going to be enough, because what’s behind the excess is the secretly longed-for oblivion that eventually arrives in the shape of an overdose, or, in Henry’s case, a policeman’s gun pointed at his head. You’ll find these conflicts in a remarkably diverse range of Scorsese films, whether it’s Kundun, Casino, The Last Temptation Of Christ, The Wolf of Wall Street or a documentary like Living In A Material World about the life of George Harrison.

Ultimately, the ‘glorious time’ when the ‘wiseguys were all over the place’ can’t last for Henry – All Things Must Pass, indeed – and so the rise inexorably gives way to the fall. But after 25 years, the reputation of Goodfellas only grows as each new generation encounters it, further embedding it in the canon of cinematic masterpieces, and proof, if it were ever needed, that its director is very far from being your average shnook.