For the true cineaste a love of terrible films is as important as a passion for the good stuff. This is nothing to do with ‘So bad it’s good’ or any of that nonsense, however. This is closer to recognising that entertainment is entertainment, wherever you find it, and all the below listed films – handpicked by our resident trashmeisters at Quietus towers – are as entertaining as all hell.

Bad cinema has crept, Caliban like, in it’s better looking brother’s shadow for as long as the flickers have illuminated the silver screen. For everyCitizen Kane there is a Manos: The Hands Of Fate, for every esteemed and lyrical Moonlight or captivatingly epic Titanic there is a twisted and becursed Garbage Pail Kids or The Howling 2: Your Sister Is A Werewolf: Knock-kneed cinematic orphans, shuffling around in the cold, waiting for somebody to love them. Well luckily, we at the Quietus are made of stern stuff and are capable of hoovering up more trash than Henry himself. The results are presented below. These are the films that, as the nights draw in, you might want to consider settling down to with warm hearts and low expectations. Some are captivatingly pretentious messes, some are lunkheaded passion projects, some are just stark staring awful, but they all possess that strange charisma that will keep you coming back to their unique charms again and again. Below, you can read all about the bad films we love, straight from the mouths of the bad people that love them.

The Neon Demon – Nicolas Winding Refn, 2016

On first sitting down to watch The Neon Demon, it’s easy to get washed away by its strobe set pieces and often dazzling visual confectionery. On a second watch, its atrocious script and preference for sometimes interminably slow shots of L.A. nightscapes and motel interiors become far more apparent. Ultimately, the fashion world is as soft a target for parody as the finest cashmere, and its overall tone thus flits uncomfortably between quite bland parody and a slightly unbearable smugness. You’d think this would add up to an unsatisfactory viewing experience, and yet, why does it leave me grinning so widely as the end credits roll? Its material crapness somehow adds to the pleasure, although I don’t think it necessarily intentional. This is a gloriously dumb, superficial and at times badly overwrought film with a core theme that isn’t entirely clear. Is it about our collective perversity and obsession with youth and beauty? The fashion world’s internalized misogyny? Actual vampirism? Like a nicely fitting jacket, it’s better just to slip it on and enjoy the sensation.

Tom Duggins

Anaconda – Luis Llosa, 1997

The late Roger Ebert once wrote "There is within me an unslaked hunger for preposterous adventure movies. I resist the bad ones, but when a Congo or an Anaconda comes along, my heart leaps up and I cave in." That quote is not only the first time I’ve come across gushing praise for Anaconda, but also the first time I’ve seen the word ‘unslaked’ in print – and I like the sound of it already. The nineties had a knack for caring somewhat about its monster films; you had to make it look reasonably convincing, and you had to spend at least ten minutes etching out something that resembled the remains of a plot before you were allowed to go all Kevin McAllister wild with the animatronics. You weren’t going to get an industrious four dimensional shark hell bent on devouring a justly spirited kraken, but you were going to get a slightly pre-fame J-Lo pairing up with a judicious Ice Cube in a bloodthirsty dance with a mythical snake.

Throw in the slimy Paul Serone, who Jon Voight seems to relish like it’s the character he’s been licking his lips for his whole life, and you get a weedy, viper-like apprentice of Colonel Kurtz who can barely contain his excitement at the utterance of one-liners such as, “Zo young….yet zo lethal!” (to a bub snake gnawing his finger), and “Five wheeskees? That’s breakfast on theee reeever!”. Voight’s wry river of darkness performance threatens to outshine that of the film’s namesake, that is, until our shrieking scaly friend finally makes an appearance about an hour in. I remember reading somewhere about how the sound people behind Jurassic Park harnessed the services of an alligator, a tiger and a baby elephant to cook up the meaty roar of their temperamental feebly armed theropod. What the people behind this gem did to arrive at the bloodcurdling screech favoured by our protagonist is anyone’s best guess. I’m gonna have a stab and say a hearty blend of harpie, baby mandrake and banshee extract. Apparently snakes don’t really scream but who’s to say they don’t wish they could? And to say nothing of the film’s influence, I could swear the basilisk in Chamber Of Secrets was making just the same kind of racket from her labyrinth in exile.

You were always going to need a sizeable cast to satisfy the hunger of a reptilian Goliath such as this one, but making away with Owen Wilson, Jonathan Hyde, Eric Stoltz and Danny Trejo as mere appetizers? The draft was of a higher standard in those days. Or maybe it wasn’t. Either way, the means of their destruction has been described as comically bad or ‘thoroughly satisfying’. I’ll let you decide. Just don’t go hunting down those sequels.

Raphael Hall

Robin Hood: Prince Of Thieves – Kevin Reynolds, 1991

From a critical point of view, Robin Hood Prince of Thieves is an irredeemably bad film. It’s as confused about what it wants to be as any work I’ve ever seen; it’s a poor, inconsistent revision of the myth, it’s terribly acted and diabolically researched, and, at times, it descends into extremely bad taste, but if it’s on, I’ll invariably cast aside what I’m doing and absorb every shot and hang on every word. This is most certainly down to the fact that it was the film of my childhood, and watching it now throws me into a delicious, nostalgia-ridden fugue.

I viewed the opening – when Costner’s Robin of Loxley arrives at the mist-obscured cliffs of Dover and detours a few hundred miles to the beautiful Sycamore Gap along Hadrian’s Wall, before heading again for home – as a perfect depiction of the dour and pallid English countryside, laden though the sequence is with puerile dialogue. The scene in which the young boy, Wulf, is chased through the fields by Guy of Gisbourne and his pack of raging hounds was a nod to the coming enclosure acts that would frustrate the common man’s relationship with the land (the boy is described, somewhat profoundly, as akin to a “game bird”). And the bit where Gisbourne then prowls into the haunted forest, the canopies rippling in the breeze, was a throwback to the golden age of British rural horror, seething with an eerie menace that’s turned quickly on its head when the ghosts are revealed to be the oppressed poor in hiding, finding refuge amid the trees – a Thoreau-like existence. It’s the politics and poetry of landscape in motion.

Of course, this is all tripe, and anything that isn’t crumbles as the film descends into a bizarre and over-embellished cross between period drama, pantomime and gothic war thriller. What’s great, though, is the action, the reams of quotable lines, the cheesy romance and the inimitable Alan Rickman – basically, everything I loved when I was 12. There’s the grotesque and petrifying witch, and Robin’s brave and resolute companion Azeem, too, whose rousing call to arms from the castle wall can still draw a tear to my eye. And who can forget the stirring Bayeux Tapestry montage at the start – accompanied by Michael Kamen’s excellent score – which has nothing whatsoever to do with the narrative that follows.

I was particularly impressed though, during this latest viewing, by the final swordfight between Robin and the sheriff, which is frantic and brutal, a desperate battle to the death, during which both men abandon style and elegance and instead hurl weapons and furniture at each other with the aim of killing outright. The sheriff’s subsequent death is straight from director Kevin Reynolds’ top drawer. It’s a style that, if employed consistently, might have saved the film from the critical abyss into which it fell, but I doubt it.

Editor’s note: The only version of the fight we could find that featured Rickman’s magnificent death acting was dubbed into Spanish. We think you’ll agree it actually heightens the experience.

Tim Cooke

The Holiday – Nancy Meyers, 2006

On paper, there is nothing about Nancy Meyers’ The Holiday that could possibly explain its sheer level of atrociousness. All the inoffensive, aspirational Meyers beats are there: everyone is low-key rich, white and wonderfully successful in all areas of their life apart from love. It looks so harmless, so of its pre-2008 financial crisis time. How could a film in which Kate Winslet and Cameron Diaz swap massive houses for the holidays and boink Jack Black and Jude Law possibly be that bad?

Worryingly easy as it turns out. The Holiday is a rat race of awfulness, with ludicrous character decisions, terrible acting and worse dialogue all competing with each other to undermine the film the most. The Holiday is a film in which Jude Law’s widower Graham calls Cameron Diaz’s Amanda ‘one the most interesting girls he’s ever met’ after she calls foreplay ‘significantly overrated’. It’s a film that then doubles down on that line by making Jude Law say the phrase ‘Most Interesting Girl Award’ without any sense of shame.

In The Holiday, everybody is so terribly broken that only the right combination of editing and schmaltz can fix them. Kate Winslet’s Iris befriends an elderly man in LA and the next day acts like she’s known him since WWII; Jude Law moves on from his dead wife and Amanda goes from a woman who can’t fall in love to step-mum in half that.

It’s the sort of film that drags you kicking and screaming over unearned emotional pay-offs, expecting you to root for characters who are about as intriguing as a piece of toast. It’s a terrible film and I can’t help but watch it every year.

Benjamin Rabinovich

Tango & Cash – Randy Feldman, 1989

Some films are good. Some are bad. Some are so bad, they are good. Tango & Cash is not any of those. Tango & Cash is a film that is so bad it transcends human understanding of concepts of bad and good. It is the Schrodinger cat of films, the Ying and Yang – occupying two states that compliment one another. Why am I mixing metaphors? you ask. Why are Sylvester Stallone and Kurt Russell’s characters called Raymond Tango and Gabriel Cash? Because their surnames sound cool if put together and that is the way of Tango & Cash.

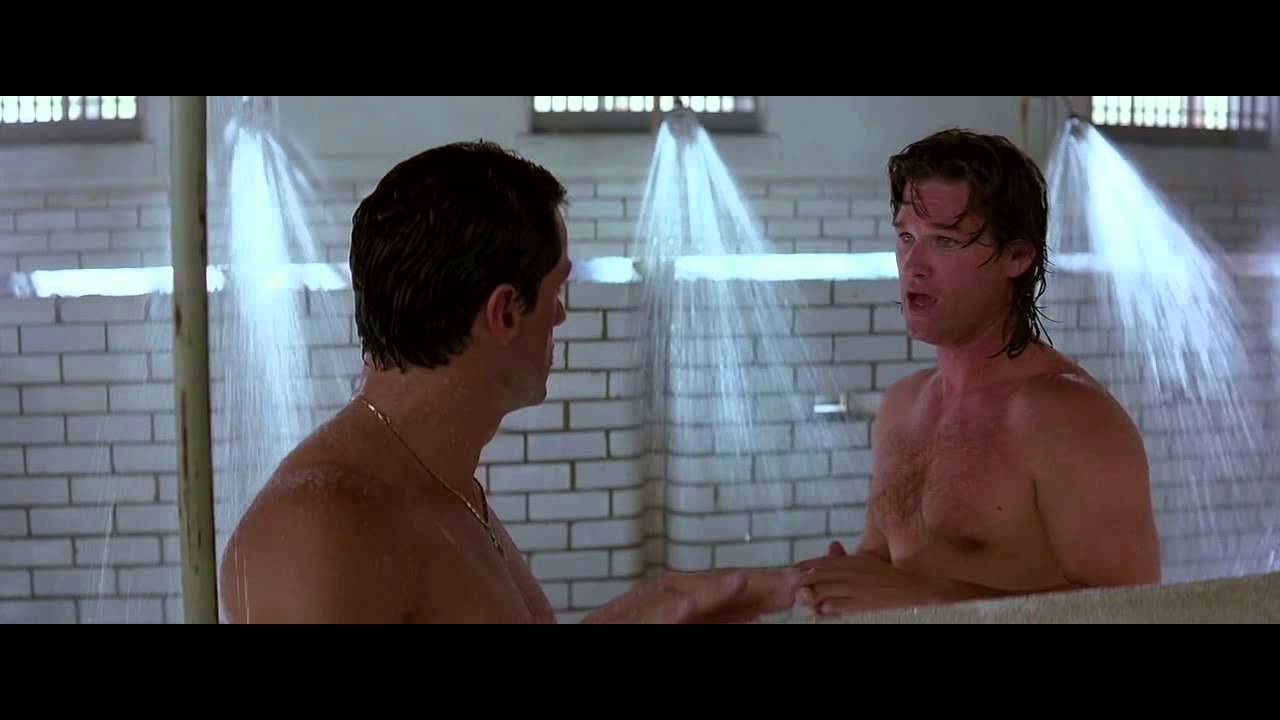

Plagued by production issues straight from get-go, Tango & Cash is a film that’s almost literally pieced together by newspaper clippings and world’s worst puns. Does Kurt Russell have to wear a drag outfit to avoid capture? Does Stallone have to make a terrible Rambo reference at the beginning of the film? Do they both have to shower together in prison and stare at each other’s penises? No, of course not, but that’s what happens and there is nothing you can do about it.

By Tango & Cash logic, there is valuable sense to be mined in nonsense and if things happen in a chronological order onscreen, then let’s come up with a cool hendiadys-sounding title and call it a film.

Benjamin Rabinovich

Black Devil Doll From Hell – Chester Novell Turner – (1984)

Thirty three years ago, Chester Turner had some oversized ideas for a construction contractor. Wanting to make multiple horror films, he engaged in a correspondence course, one instructional video at a time. Simultaneously working on his films, as he learned the basics of making them. Black Devil Doll From Hell was the first result. Made with little more than a camcorder, a cheap Casio keyboard to provide the soundtrack, and a ventriloquist doll made up to look like singer Rick James, this film is DIY at its most screamingly bizarre.

First encountering this title ten years later, when my friends and I would gamble on horror films at the video rental store based solely on the covers, I can still remember our stunned reactions through the entire viewing. That copy of this film took on an almost legendary status in our town, as every manner of freaky teenager had to see just how bad it was. And make no mistake, this film is bad. On every level, the aesthetics and content will pain your soul. The plot is your basic "good woman buys doll, doll turns out to be an abusive lover, woman finds she needs that sort of thing in her life, doll kills woman." It would be next-to-impossible to sell a potential audience on that premise, but Mr Turner tries his damnedest. Worthwhile for its "I bet you’ve never seen this" value, it also conjures the hope that no one ever attempts something like it again.

Haakon Nelson

Man Up – Ben Palmer, 2015

Romcoms are for emotional invalids: us hungover, heartbroken and harrowed heaps of human flesh, wibbled and snotting under the duvet. Ironic, then, that the films angled at those amongst us who are most in need of emotional sustenance drift towards Simon Pegg vehicles. Man Up falls into this mire of a genre: starring and produced by him, its plot is the route of a long, dull day spent crawling through central London’s most clichéd ‘date spots’. Nancy (Lake Bell) and Jack (Simon Pegg) ‘meetcute’ by accident in Waterloo station: he mistakes her for his blind date, and she plays along. At the end of the date, Nancy reveals that she was not the woman he was planning to meet. He renounces the day as a failure; Nancy agrees, despite having enjoyed herself for the first time in forever.

She leaves disappointed and arrives late to her parents’ anniversary party, where she had promised to make a speech, feeling embarrassed and self-pitying. In her speech – the sole consolation for anyone who commits to all 87 minutes of this Fitzcarraldo of dating – she admits to lying her way through this date, and finds something admirable in herself. She went along with the deception, not because she believed it would work, but because it offered a return to ordinary life: real, and bittersweet, nothing guaranteed. Man Up is weak, but hopeful – the very medicine a hangover deserves.

Ellie Broughton

Strike Commando – Bruno Mattei, 1987

A sadly unfamed entry in the disreputable ‘Rambo-sploitation’ genre (or, as it’s otherwise known ‘Vietnam-never-ended-so-we-haven’t-actually-lost-yet-so-go-suck-a-fat-one-USA!USA!-sploitation’), Italian schlock lord Bruno Mattei’s Strike Commando is solid action entry delivered into the hands of a higher power by some magnificently… um, lively performances, a body count that rivals that of Passchendale and a scene that sums up so perfectly what it is that I adore about this paticular brand of trash. Not an action scene, or one of the many decidedly homoerotic torture scenes that pop up with alarming regularity, no in this scene our protagonist Sgt, Michael Ransom (possibly the most white, anglo-saxon name imagineable), snivelling through tears of pure actorly commitment, guides a poor dying little laddie toward the eternal light, telling him of a mythical place, a kingdom situated beyond the vale of dreams, a land called Disneyland, where apparently there is ‘Tonnes of popcorn, and all you have to do is climb a tree to go eat it.’

There are a few questionable aspects to this scene, even putting aside Mattei’s extremely strange idea of how it is Disneyland actually works – were you to actually climb a tree in The Happiest Place On Earth you would be tasered by a former Navy SEAL dressed as a chipmunk – but I can never help but be swept along grinning by its pure, heart-on-sleeve idiocy. It’s the thickest moment in a film filmed with thick moments, topped off righteously by our pure-blooded hero bellowing the name of his arch-nemesis into an echo box while cradling the body of a dead child. It’s morbid, it’s stupid, it’s offensive and I whoop with joy every time I see it.

Mat Colegate