The (wholly justified) praise heaped upon Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln widely comments on the film’s central preoccupation with the formalities, procedures and rituals of legal court proceedings. Robert Zemeckis’s Flight is a film that sets itself up for a similarly fine tuned examination of contemporary legal machinations, though it ultimately trips over its own feet, becoming embroiled in an all too familiar addiction-conquering sub-plot, which is in turn hampered by major inconsistencies of tone and mood.

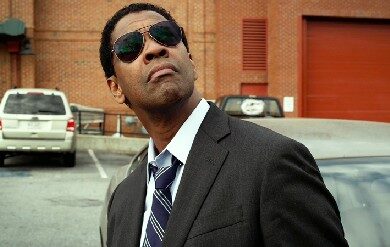

However, Zemeckis’s return to live action film making (following a triptych of wholly sub-par motion capture works) is announced with a furiously fun and energetic opening thirty minutes. The film opens in a disheveled hotel room with pilot Whip Whitaker (Denzel Washington) righting his misdemeanors of the previous night with a line of coke. From the stylistic choices within this opening it is evident that Zemeckis has missed live action film making; he flashily (though somewhat mid 90’s trope-ily) throws the camera into Washington’s face as he hits the line (its overworked and overdone, but you can’t help but enjoy it). Whitaker heads for the airport, guiding his SouthJet flight through heavy turbulence, mixing up a vodka orange and taking a well earned snooze as the plane sits atop the clouds. Disaster soon strikes however with a mechanical malfunction sending the plane into a steep dive. Whitaker instantaneously takes command and in fantastically implausible fashion turns the plane a full 180 degrees before guiding it into a crash landing, saving all but six passengers. Zemeckis’s use of slow motion and lilting stedicam shots throughout the crash and its immediate aftermath gloriously fetishises every horrendous malfunction and moment of human turmoil. His focus here is less on individual plight but rather a wider focus on the spectacle of the crash itself, and it works horribly well.

Whitaker’s awakening in hospital brings about one of the film’s all too few moments of subtly nuanced anguish. Zemeckis stylistically shifts gears, using largely static and repeated set ups, in marked contrast to the frenzied opening- where he was perhaps a little too keen to stylistically mark his return to live action. The initial reassurances offered by Whitaker’s union representative and Navy buddy Charlie Anderson (Bruce Greenwood) are undone by a subtle pan, which indicates that NTSB representatives are noting down every word spoken.

The shift in tone and style between the film’s frenzied opening and the slow burning of Whitaker’s awakening provides a solid frisson which, it quickly and disappointingly becomes apparent, Zemeckis cannot maintain. Two sequences that quickly follow this opening pair release almost all the tension the film has worked to wind up. The film introduces two characters, one parodic and trite the other interminably boring, both of whom are ultimately unwarranted and distracting. The first is John Goodman’s cameo performance as Whitaker’s drug buddy. Clearly he’s there to show Whitaker’s “zany” past, but it’s perhaps the most tonally ill suited performance in any film of the past year. The second is Kelly Reilly’s drug addicted Nicole, there to provide Whitaker with the impetus for the flattest and dullest journey towards sobriety and redemption seen on screens for a while.

What these two formulaic characters suck from the film is the potential for any significant screen time to be devoted to the legal push and pull surrounding Whitaker’s court case. Don Cheadle as Whitaker’s union defence attorney is terrifically blunt and practical. He quickly sets up the moral and ethical dilemmas of such large union court cases – personal responsibility and guilt versus collective punishment and fiscal loss. Sadly though we never see enough of him or of the court case.

Zemeckis’s film has the potential to structure itself around some meaty ethical and legal dilemmas, but instead it formulaically crashes and burns. By the end there are no survivors.

Flight is out in UK cinemas today