So, by now I’m sure you will all have taken time to watch Steven Soderbergh’s illuminating black and white re-framing of Spielberg’s Raiders Of The Lost Ark. If you haven’t then you can find it <a href="http://extension765.com/sdr/18-raiders target="out">Here.

I’ll wait. For an hour and a half. Don’t worry about it. Fuck’s sake…

That was a fascinating experiment, I think you’ll agree? The film is thrown into a new light and the viewer is given a fresh appreciation of its director’s skill by the simplest of means. It’s a timely and elegant conceit. However, such efforts can be taken further. It’s one thing to stop and smell the roses when it comes to the way the action is framed, but what about similar experiments exploring the more behind-the-scenes aspects of the film making experience? A blind taste test to determine the greatest on-set catering, perhaps? Whose clapper-board work is the most limber? Who is the fastest ‘runner’?

But then it struck me. What about an exercise to reflect upon the respective recognisability of the much loved theme tunes that accompanied the on screen ding dongs of our favourite multiplexional heroes and villains? How about an experiment in removing them from their familiar contexts and making them stand tall as the great pieces of art at they are in their own right?

With this in mind I would like you to read the below and guess which theme tunes are being represented. Answers at the bottom of the introduction:

1: DA DA DA DA DA DAA DAA DAA/DA DA DA DA DA DAA DAA DAAAAAAAAAAA!!!!!

2: DAAAA DAAA DA DA DA DAAAAAAA DAAAAA DA DA DA DAAAAAAA DAAAA DA DA DA DAAAAAAAA!!!!!

3: DA DA DA DAAAAAA DA DA DAAAAAAA DA DA DA DAAAAAA DA DA DA DA DA!!!

4: DA DA DA DADADA DADADA/DAA DAA DAA DADADADADADAAAA!!!

The answers are:

1: Superman! C’mon, that was piss easy…

2: Indiana Jo… No! Star Wars! That’s Star Wars…

3: Okay that’s Indy… No hang on. Is it the one that gets used on all the Darth Vader bits?

4: Okay, number two is the Darth Vader one, definitely… this is… Jaws? Y’know, the jaunty bit that no one can ever remember? Looking back I think number one might be Ferngully: The Last Rainforest.

5: ET! Fucking ET! It’s fucking ET! No, listen its fucking ET! Oh, hang about…

6: Jurrassic cunting park

Well that didn’t work.

With the sound of orchestrated failure ringing in our ears I think we should probably move on to this weeks round-up, don’t you? Let’s try and put all of this behind us…

Reviews this week by Yasmeen Khan, Katherine McLaughlin and Mat Colegate

Ida (dir: Pawel Pawlikowski)

From the outset, Paweł Pawlikowski’s Ida is uncompromisingly in the European arthouse tradition. It’s 1960s Poland. It’s black and white, it’s Academy ratio. There’s long shots, silence, snow, statues, Catholic nuns. Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska) is a young novice about to take her vows, when her prioress sends her off to meet her aunt Wanda (Agata Kulesza), who had refused to take her in as a child. Wanda informs Anna she’s actually Jewish, her birth name was Ida and her parents were murdered during the war. The strangely pliant, self-possessed Anna acquiesces in the mystery, and the two women set off to search for her parents’ graves in what will become a journey of self-discovery for both. The film is a kind of meditation after that on what a coming of age story ought to mean – what else needs to happen to give meaning to a formal rite of passage? What does Anna/Ida need to learn about her past and herself before she can be lost to the convent forever?

In tone and subject, Ida has a feeling of an Aki Kaurismäki film, bringing to mind 1999’s Juha, the black and white tale of a country wife caught in the trap of the big city. Although Ida dials the absurdism down to a whisper, it’s definitely there – the crazy music, the slightly eccentric characters sitting alone in bars, the juxtaposition of stained glass and cow shit that describes a rural church.

Ida is also strikingly, classically beautiful. Its luminous cinematography has something reminiscent of Ingmar Bergman, say, with a sense that any frame you might stop on would be a perfect composition. That’s not to imply it’s over-careful. From the evocative descriptions of lonely places, empty, dreary land and bleak little towns, to the portraits of solemn, dark-eyed, expressionless Ida, the visual is definitely the emotional here, too. There are hypnotically arresting, moving scenes – a skull, a bath, Joanna Kulig singing. This is a film of powerful vignettes.

Ida, is a gem, and, after the slightly disappointing The Woman in the Fifth (2011), something of a return to form for Pawlikowski. Not that there’s anything formulaic about his career. Before making the switch to fiction with the wonderful Last Resort (2000) and My Summer of Love (2004), he was known for his poignant, slightly absurdist documentaries depicting the strange characters and aesthetics of a particular vision of Eastern Europe, and Ida feels in some ways like a return to this sensibility, distilled into fiction. Its entwining of beauty and emotion make it a rewardingly cinematic experience. Yasmeen Khan

Honeymoon (dir: Leigh Janiak)

Soured matrimony is the subject placed in the capable hands of Leigh Janiak, who in her debut feature casts the versatile Rose Leslie as a newlywed who goes through a strange transformation on a holiday to a quiet lake cabin. Janiak cites Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby and Invasion of the Body Snatchers as influences on her taut psychological horror, but There’s also a hint of Cronenberg as the giddy heights of romance and coupledom sink to devastating and icky lows over the course of four days.

Janiak collaborates with Philip Graziadei on a screenplay which chooses to focus on the interplay between Bea (Leslie) and Paul (Harry Treadaway) in a singular, claustrophobic setting. An opening credits sequence introduces us to the couple on their wedding day, where they speak directly to camera from a cosy, fairy-lighted tent set up on their bed and explain how the universe tried to keep them apart. Janiak chooses to intercut intimacy with menace as she poses the question: how well do you know you know the person you’ve just agreed to spend the rest of your life with?

Last year at Frightfest director Jeremy Lovering tackled the anxieties at the start of a relationship with In Fear. Honeymoon takes this idea one step further, and also rightly found a home at the festival this year with Janiak being one of three female directors to showcase a feature film. Traversing similar grounds with a female gaze brings with it a fresh perspective and casting Rose Leslie alongside Harry Treadaway certainly pays off, as the two present believable and sympathetic characters.

Bea begins her break as an outgoing, capable kind of girl but on the couple’s idyllic jaunt to her summer vacation cabin paranoia rears its ugly head as they realise that they might not know one another as well as they think. Paul awakes one night to find Bea in the middle of the woods, stripped naked and strangely vacant and he and is spun into a storm of confusion; a lost man trying to map his way back to his wife’s heart.

Director Of Photography, Kyle Klutz, makes good use of darkened, claustrophobic interiors, and The vistas of North Carolina, the glistening sunshine on the isolated lake and the chilling detours through a fertile forest in the dead of the night are handled with ingenuity creating both a striking and startling backdrop.

Issues such as the pressure on women to procreate and outdated marital values are tackled insightfully. Bea slowly loses her identity, her memory fading as her marriage continues. She forgets who she is, frantically scribbling notes about her life in New York into a secret diary. She becomes swallowed up by her vows. At one point early on, after a heated session of lovemaking, Paul jests at Bea to “rest your womb”. Fears for the future and decisions not even thought of are starkly brought to their present.

An unflinchingly grim and gooey conclusion combined with the superb performances cements Janiak’s hopeless vision of marriage and the terror of uncertainty into the consciousness long after viewing. Katherine McLaughlin

Night Of The Comet (dir: Thom Eberhardt)

Arrow Film’s recent run of excellence looks set to continue. Not content with being part of the team behind The Honeymoon (reviewed above), their Arrow Video imprint has recently reissued some hyper-cult classics for the first time in an age. And, following lovingly packaged reissues of Suzuki’s Branded To Kill and Petri’s L’assassino, 1984’s Night Of The Comet is the latest to be given the rebuff treatment. And what an utter charmer it is too.

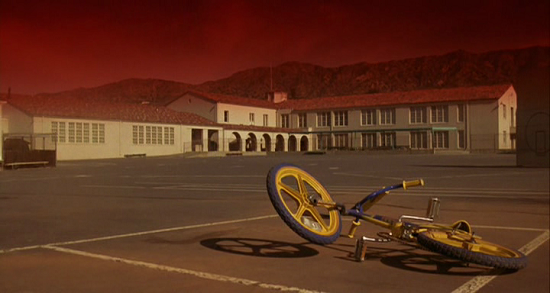

Thom Eberhardt’s film is, on the face of it, a tribute/rip-off of all those classic day-after-the-world-ended movies (Day Of The Triffids, The Omega Man etc), lots of shots of empty cities (in this case a dazzling looking LA), survivors groping their way through the wreckage, and irradiated freaks thirsty for blood. But Night Of The Comet stands apart from the pack by virtue of its odd pacing, likeable characters and surefooted grasp of its era. Because make no mistake, this is an 80s movie. Maybe even The Ultimate 80s Movie, which goes to make its contemporary appeal even more surprising.

Following the appearance of a strange comet, two valley girl teen sisters (played with brilliant, big-haired breeziness by Catherine Mary Stewart and Kelli Maroney) awake to find a depopulated Los Angeles, and, like any self-respecting teen girls would, proceed to use it as a playground of wilful destruction, vehicle theft and shopping sprees. The only problems are the glassy eyed, mutated survivors and a team of doomsday scientists (led by Mary Woranov in her full Annette Peacock-meets-Elvira gaunt glory) determined to capture them and harvest their blood. Cue explosions, dance scenes, Mach 10 machine guns (crucially, not Uzis) and the most invasively loud saxophone powered soundtrack this side of Baker Street.

Night Of The Comet is a very (perhaps unintentionally) odd film. It marries the slack do-anything-you-wanna-do pacing of the best 60s underground films – George Kuchar, say, or Jack Smith – with a dialled-in apocalypse plotline, loveable teen protagonists and some of the most singular cinematography of its era. Depopulated LA looks gorgeous – a lifeless skyscraper-crammed vista of cold sun and dusty pink smog. Nearly every city shot could be paused, screengrabbed and used as the background picture for some hideously blank and nihilistic youtube vaporwave joint. But the fun isn’t all cosmetic, Stewart And Maroney are extremely likeable throughout and their relationship is depicted in just the right mix of broad and soft strokes to keep them interesting. You’ll be rooting for them all the way until the charmingly carefree shrug of an ending.

While never a hit at the time, it’s worth watching Night Of The Comet in order to track the progress of its DNA through various B movies and horror big hitters. Sean Of The Dead, for sure, but I’ll be absolutely buggered if Boyle and Garland’s 28 Days Later hasn’t also licked at its wounds (and come up about a hundred times less enjoyable as well). But whatever your reasons for checking it out, Night Of The Comet is a refreshing blast of hairspray scented fun from crop-topped top to pop-socked bottom. Mat Colegate