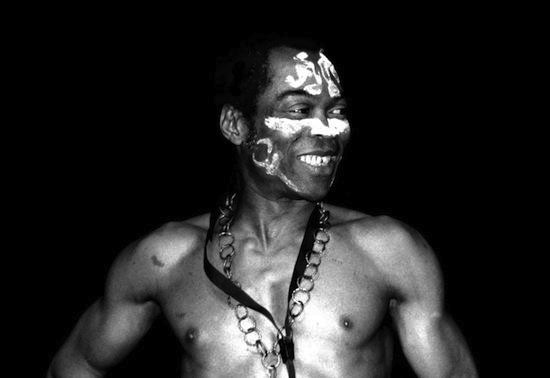

Given the opportunity to go back and witness any musical force at the peak of its powers, seeing Fela Kuti at The Shrine in Lagos would be hard to beat. This was the venue where Fela held a residency with his groups Africa 70 and later Egypt 80 – and the place was full night after night. Fela’s huge ensemble included percussion, guitars and horns, a female chorus of backing singers and dancers, as he delivered his Afrobeat music that combined a swinging mix of highlife, jazz, funk, and soul that “created a form where there had been no form”. The powerful music was not just to get people dancing however, as Fela always included a heavy message, with themes of social justice as his lyrics attacked the corrupt forces ruling Nigeria.

The closest many of us will ever get to experiencing the unparalleled spectacle of dancing, fluid groove and hypno repetition that Fela and his large groups of musicians and dancers specialised in might just be the recreation of The Shrine’s mythic stage setup for the Fela! musical. Fela! debuted in Broadway in 2009, and made its way to London in 2010 and 2011. It is the journey that eventually took the show to Lagos in 2011 that forms the basis for Academy Award winning director Alex Gibney’s new biopic Finding Fela. The original idea for the film was to trace the “homecoming” of the Fela! show as the cast took to the boards at The New Afrika Shrine. However, as archive footage of Fela in his prime was unearthed it became clear that the man himself had to feature more prominently, his message still as relevant as ever. And this approach provides an interesting foundation for a reappraisal of the visionary Afrobeat pioneer.

Perhaps it is no surprise that Sir Paul McCartney, Stevie Wonder and James Brown made the trip to the Lagos hotspot to witness Fela in action. In the film the former Beatle reveals: “I ended up just weeping, the band were unbelievable.” Cream drummer Ginger Baker went one further and got onstage, even staying on to enjoy the party for a while – until he got a little too cosy with the polo brigade, an elite set that numbered many of the very people Fela was railing against. Ginger’s time in Nigeria resulted in the recently reissued 1971 Fela With Ginger Baker Live! LP. And with Fela’s 75th anniversary reissues campaign last year, the arrival of Finding Fela picks up on the renewed interest as a new generation of fans are introduced to his work.

For people in Nigeria the legend of Fela Anikulapo Kuti was no secret, despite attempts by authorities to curb his influence. Fela gave a voice to their story and a vision of hope in which to believe, and many who may have otherwise had to turn to crime were taken off the streets and employed by Fela in the independent state he called home – the Kalakuta Republic. While his music may have been banned on the radio, you could still hear it on the streets around the capital, the military-baiting anthem ‘Zombie’ defiantly blasting from speakers. Fela’s legend was such that on his death in 1997 more than 1 million people turned out on the streets to say goodbye to their hero, the revolutionary spokesman for a generation – the self-proclaimed Black President. “I hold death in my pouch, I cannot die, they cannot kill me,” Fela proclaimed. And they (police, military, the establishment) could not, despite more than 200 arrests and countless beatings that left his whole body battered and scarred from the brutality of the authorities, who did not take kindly to Fela’s naming and shaming approach to uncovering the corruption at the heart of the Nigerian government, as the elite classes siphoned off huge amounts of money made from oil.

Finding Fela captures critical behind the scenes moments in the development of the musical, as director and choreographer Bill T. Jones uncovers and explores the true meanings behind many of Fela’s songs, their messages and structure, and how they can be worked into the storyline. Jones acknowledges that many of the theatre-goers seeing the show would not necessarily be Fela aficionados. The musical combines Fela’s hard hitting story with a live soundtrack, with the Africa 70 and Egypt 80 sound ably recreated for the stage by New York Afrobeat group Antibalas. In the film there is some fantastic footage from both the musical and Fela in action, including clips from the 1978 Berlin Jazz Festival and the 1984 Glastonbury appearance. After Berlin, many members of the Africa 70 group left the fold over money disputes and the “reserve team” was brought in, with the formation of Egypt 80 – which included Fela’s son Femi on sax and signalled a “new era for Afrobeat”.

Fela’s children Femi, Yeni and Seun (who now fronts Egypt 80) are all interviewed in the film, along with Africa 70 drummer Tony Allen, manager Rikki Stein and Lemi Ghariokwu, the man behind many of the iconic sleeve designs for Fela’s records. It seems that while life was not always easy around Fela, he never lost the respect or love of those close to him. As Femi admits, “We got everything,” but, inevitably with so many people around, they got the “love last”. By the mid ‘70s there were around 200 people either living at or working for Fela at the Kalakuta Republic, and around this time he married 27 women simultaneously. Some aspects of Fela’s lifestyle appear to test the resolve of the Fela! production team, who chose to leave out the details of his AIDs related death in 1997, although this is explored in the film, as Fela’s brothers, both doctors, aimed to raise awareness of the condition.

The 1977 raid on the Kalakuta Republic was one of the most traumatic experiences for all close to Fela, following which his mother died due to complications from injuries sustained in the clashes. Tony Allen said the events “tripled” his resolve to carry on with his mission, “He was really mad.” Fela also turned to spirituality around this time. He increasingly relied on the guidance of Professor Hindu, who for a time, went everywhere with him as his spiritualist and guru. In addition to appearing onstage with Fela at concerts, the film also tells the tale of one quite disturbing showcase of his voodoo powers in front of a live audience in a club in London.

Outside of the devotion of his supporters it seems that Fela’s message and delivery of his “sophisticated” Afrobeat music was too extreme for a wider audience at the time, perhaps more accustomed to the “easier” Bob Marley. When Rikki Stein approached record executives from top labels to secure a deal, they were only interested in the three minutes they could get on the radio, however many of Fela’s recordings filled a full side of vinyl, often topping the 20 minute mark. To his credit Fela never compromised either his music or his politics in expressing his singular world view. The music was what it was and had to be taken as such. And the same was true of Fela’s message. On occasions when he took his muisc on the road, like in Berlin, he told the crowd that “99% of what you hear about Africa is wrong.” The legacy and music of Fela Kuti was built to last, and Finding Fela offers a fascinating glimpse into his story from the people closest to him.

Finding Fela is out now at selected cinemas, see here for full listings: http://findingfela.co.uk/screenings.